I Is Another

What accounts for the enduring appeal of Germany’s cult experimental author Hubert Fichte?

What accounts for the enduring appeal of Germany’s cult experimental author Hubert Fichte?

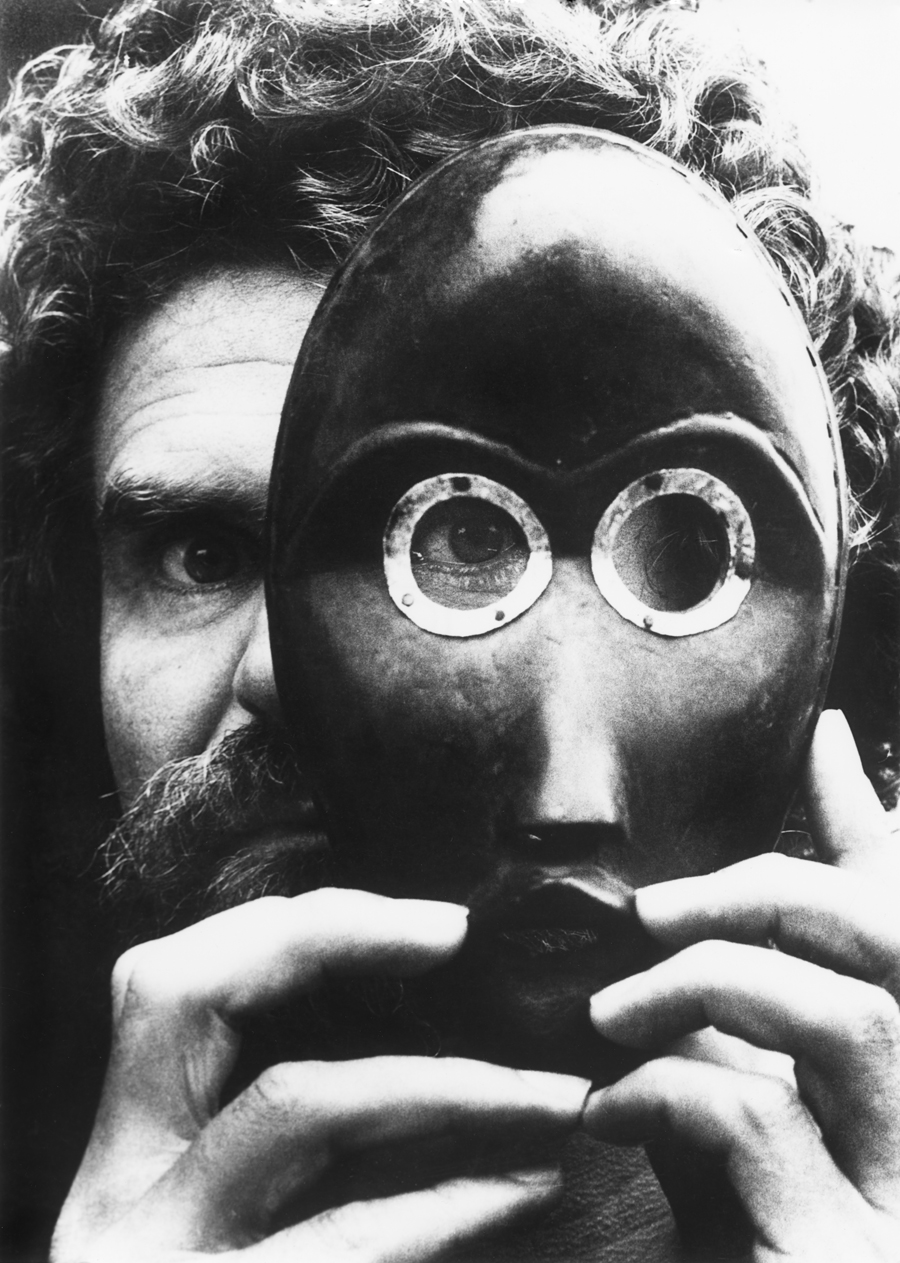

Some know Hubert Fichte as a Hamburg author with vague pop leanings. Others have sought to distance him from the category of ‘gay writer’ by declaring him a model for authorial constructions of subjectivity. On the whole, however, Fichte remains little known: a cult writer, even in Germany. His obscurity seems all the more surprising given that his work displays a breadth of scope and personal actions rarely found in German art and literature. Fluent in numerous languages, Fichte was constantly travelling, penning unique ethnographic, journalistic and literary texts that offer entry points into postcolonial discourse today.

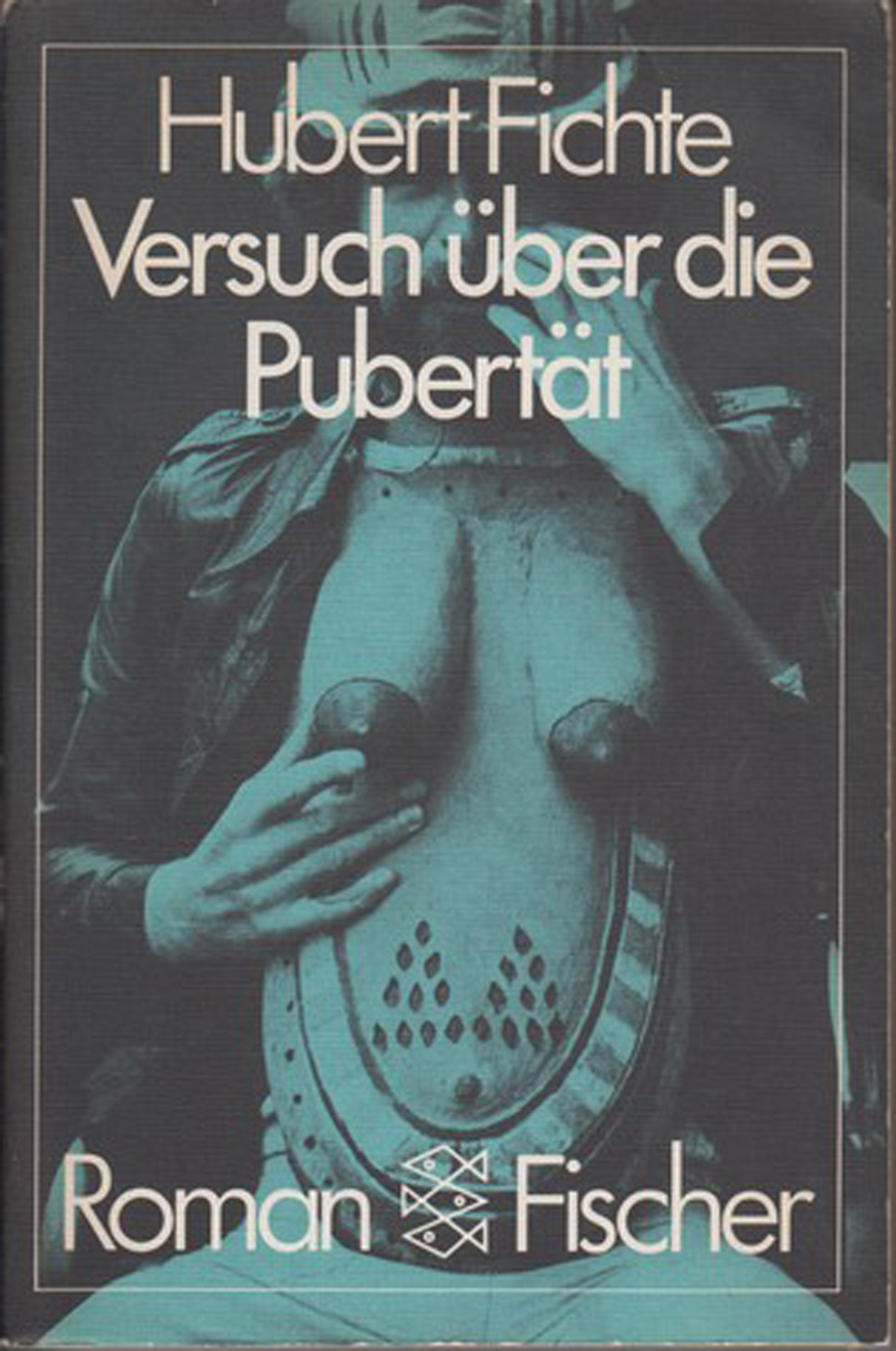

About once a decade, though, there is a modest but persistent surge of interest in Fichte, who died of AIDS in 1986 at the age of 50. Hamburg’s Schauspielhaus is currently staging a version of the writer’s On Puberty (1974) and his readings have recently been revived in Berlin and Hamburg. He’s also surfaced as a point of reference in works by a wave of artists in Germany, including Nadja Abt, Philipp Gufler, Birgit Megerle and Ariane Müller. In 2017, ‘Hubert Fichte: Love and Ethnology’ – a large-scale, two-year exhibition and translation initiative conceived by Diedrich Diederichsen and Anselm Franke – kicked off with a show at Lumiar Cité, Lisbon. The project will conclude in 2019, in Berlin, following a series of workshops, performances and exhibitions in key locations Fichte travelled to: Salvador de Bahia and Rio de Janeiro (2017), Santiago de Chile and New York (2018), and Dakar (2019). Fichte’s writings, hitherto mostly untranslated, are now appearing in English, French, Portuguese, Spanish and Walof, and are ripe for re-evaluation.

Why does the elusive Fichte repeatedly take a hold on the cultural imagination in Germany – as perhaps he soon will abroad, too? The story could start with Hans Henny Jahnn, who introduced Fichte to the particular low points of German cultural history. The circumstances of Fichte and Jahnn’s meeting in 1950 are so strange that they shouldn’t go unmentioned. Jahnn was a well-known novelist and playwright, as well as an advocate of German Lebensreform (life reform) movements in the 1920s. Following a period of exile in Denmark during World War II, he turned to the scientific research of proteins. In this capacity, Jahnn visited schools asking teenage boys to donate urine samples. It was then that the regal but ageing Jahnn, gay but married with a child, first met the 14-year-old Fichte. Fichte wrote of Jahnn’s ‘abysmal erudition’ in On Puberty, yet his intellectual influence was reflected in Fichte’s monographic essays on Thomas Chatterton, Herodotus, Marcel Proust and François Villon, which offered early queer readings of these writers. Jean Genet (with whom Fichte conducted a book-length interview in 1975) had a similarly great impact on his work. Genet’s disruptive yet affected style, as well as his infamous and provocative gestures of homosexuality, became exemplary for Fichte. the two of them shared a proclivity for ruth-lessness and for all forms of violence. Fichte appropriated Genet’s art of self-exposure and made similarly productive use of self-abuse. For Fichte, one foot firmly planted in German expressionism, this included the perennial motifs of the morgue and the ravaged body.

Early in his career, Fichte eagerly adopted the role of pariah in the German literary world. Gay, half-jewish, an illegitimate child brought up in an orphanage (an experience reconfigured in his first novel, The Orphanage, 1965), Fichte extrapolated from these traits a lifelong sense of entitlement to shamelessness and impertinence. From early on, novels such as The Palette (1968) – about the bohemian scene at a Hamburg dive bar – demonstrated great stylistic tenacity. Shaping observations into adroitly wrought sentences, Fichte’s verbal inventory playfully (or by way of quotation) spanned the brashly colloquial and the utterly stilted. elsewhere, Fichte’s reduction of language into enumerations and lists spared him any excessive effort at description while accommodating his dry parataxis. Repetition, idiosyncratic punctuation and the peculiarity of making each sentence its own paragraph added to the impression of a compelling modernist style. These works are like flicker films of fragmented pieces of the present. The syncopated, montage-like elements of his work also produce a sound and force that can flash into lyricism or litany.

The modest commercial success of The Palette enabled Fichte to set off abroad. He and his life partner, the photographer Leonore Mau, secured reporting commissions from Brazil for major German publications like Der Spiegel and Die Zeit. In early 1969, they arrived in a country that represented the ‘absolutely other’ for Fichte. In the late 1960s, Brazil was a military dictatorship (and would remain so for another decade), but was becoming a popular tourist destination. A flight to Brazil, as Fichte tallied in one of his novels, cost more than four months’ rent; but, just a few years earlier, it had been seven times more expensive. In Rio de Janeiro, they visited favelas, appraised the local newspapers, met with politicians and expats. Fichte took stock of the architecture, fashion, local cuisine, plants and animals. His expressionist tendencies found a reference point in the exercise of power in brazil, where murder and torture were part of everyday reality. Fichte reported on religious ceremonies; Mau took photographs of ‘blood baths’. He systematically researched sleazy cinemas, saunas and toilets to ensure a constant flow of sex with men after dark. This afforded the materialist in him information about the ratio of local prices to incomes.

Fichte was initially fascinated by the role of material poverty in religious practices and the improvisational element of ritual assemblages. He took interest in the syncretistic forms of worship that grew out of everyday catholic practice into popular religious traditions which were persecuted but not entirely clandestine. He liked the fact that incense wafted out of rusted tins rather than the opulent thuribles used in the catholic masses of his childhood. He was fascinated by the mingling of seemingly irreconcilable elements – including Yoruba and Bantu worship, African deities, Catholic saints, Masonic and indigenous practices. like Pier Paolo Pasolini, Fichte was attracted to atavistic cultural forms, claiming to see in syncretic religions the reverberating traces of earlier times.

He soon focused on Candomblé, which struck him as more archaic and complex than other syncretic religions. Even better, many Candomblé priests and priestesses were gay, and the representation of homosexuality was permissible in the religion’s pantheon of deities. Fichte flung himself into this uncanny and complex realm, taking a characteristically meticulous approach to recording the names of the gods and goddesses, as well as rituals and hundreds of medicinal herbs. The theatricality of wild trance states did not escape his notice nor did the competitive and vengeful side of some Candomblé dignitaries. Fichte was especially impressed by the therapeutic aspects of sacrificial rites, trances and the use of drugs and potions, seeing in them an independent knowledge system. The goal of the Candomblé initiation ritual is to break the pre-initiate’s hold over their consciousness, to generate an extremely overpowering experience that transforms the brain and entire person. This ‘breaking’ became the leitmotif of Fichte’s drive for knowledge. It functioned like a form of psychoa-nalysis or psychiatric treatment without actually going through psychotherapy.

Fichte and Mau returned often to Latin America. In 1971, they stayed for a year, visiting other Brazilian states and the Amazon region, then Haiti, Mexico, the Dominican republic, Trinidad and Venezuela. With the hubris common to many autodidacts, Fichte soon adopted a competitive stance in relation to his ethnological predecessors, whom he accused of theoretical errors, hasty field research and sloppiness in learning local languages. He spared nobody: Claude Lévi-Strauss (‘structuralism is puffed-up non-sense’); Marcel Mauss (‘reading him, i recognize the colonialist traits that the humanities bear in industrialized countries’); Jean-Paul Sartre (‘only interested in people if they’re miserable’). Fichte regarded his own erudition as superior, brashly dubbing it ‘new ethnology’ and ‘ethno-poetry’. Eschewing theoretical overreach, his approach started from the broadest possible empirical foundation, only then finding linguistically adequate forms of radical alterity. He saw political relevance in Afro-Brazilian rituals – beyond their relationship to homosexuality – believing they provided an avenue of escape from a Western culture that offered no way to feel comfortable in one’s own skin.

In the mid-1970s, Fichte began to publish the results of his ethnological studies as radio features or magazine essays. His novels Xango (1976), Parsley (1980) and Lazarus and the Washing Machine (1985) were intended as paralipomena to The History of Sensitivity (1986–2006) – a cycle of novels modelled after Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1922) – which also incorporated ethnographic material. Of 19 planned volumes, he completed six by the time of his death. Since then, 11 have been published. in Explosion: A Novel of Ethnography (published posthumously in 1993), Fichte extensively retraced his 13-year engagement with Afro-American religions, gathering encyclopaedically arrayed items, programmatic statements, newspaper excerpts and journalistic writings, with a great deal of material incorporated through interviews. The novel has a strong autobiographical tinge and contains a lot of sex. The not-unpretentious main character, Jäcki, written in the third person, is easily recognizable as the author himself.

Fichte’s attempts to meet the overpowering and possibly transforming qualities of the ‘absolutely other’ were not restricted to literary representation. disinterested in preserving the foreignness of the foreign, his approach asked for touch and physical intrusion. This demand could only be met through intensive acts of penetration, in which love, devotion, curiosity, an investment of time and perseverance converged. Sex, including prostitution, was an essential part of his ethnological endeavour – synonymous with access, permeability and the real: the more promiscuity, the more intrusion and empiricism. His ineluctable standard in assessing political claims was how successfully they promoted the social inclusion of homosexuals. ‘I can only imagine utopia as the total queerification of society,’ he wrote in the ‘Old World’ volume of The History of Sensitivity, expressing a desire for conditions in a new world.

On his last visit to Brazil in 1981–82, Fichte noted the decimation of rainforests, the mushrooming high-rise buildings, the vulgarization of Candomblé. Similarly, the conclusions he’d originally reached during his Latin American experiences had been evolving since 1970. While Afro-American ritual practices had initially struck Fichte as a strategy for enduring exile in diaspora, he later emphasized the role they played in resisting slavery, hopelessness and racist discrimination in places where a counter-history of African American relations since the Atlantic slave trade was continuing to take shape. By the mid-1980s, his theories centred on the term ‘bi-continentality’, a notion resonant with bisexuality. For Fichte, the impact of Afro-Brazilian religions was no longer about identities but transfers. Syncretism became a specific form of a universal rule of cultural exchange. this is why so many of the leading characters in Explosion are figures of transition: Afro-Brazilians who have long bristled against Candomblé; white europeans who have become its most famous priests. Fichte called these individuals ‘counter-columbuses’, realizing a state of ambiguity and dispersal that renders obsolete every identity claim to ethnicity, race or sexual preference. Everyone can take part in this postcolonial inversion – even a white person, even when socialized in Germany.

This is not to say that Fichte’s views are compatible with the notions of postcoloniality and decolonization that have come into focus – belatedly – in many recent European exhibition programmes. It would be easy to find colonial remnants in his ‘ethnopoetical’ approach. Regardless of whichever postcolonial agenda Fichte’s proposals might fit today, ultimately he believed that decolonialization worked as an inversion of colonial pasts rather than a reversal. His demand for exchange did not embrace restitutions of historical debt. It did, however, embrace the subjective foundation of knowledge, based on a notion of otherness as a fundamental constituent of all human experience. This idea acts as a powerful barrier against exoticizing the ‘radically other’, which is why the contemporary relevance of Fichte’s life and work tends to serve artistically motivated research that does not approach its object in academic, dogmatic or biased ways. Another important impetus that can be drawn from Fichte’s writing is to maintain the greatest possible distance from shame, guilt, nostalgia or ironic detachment. This is quite difficult to grasp – and even harder to accept.

Translated by Jane Yager

ARTISTS' RESPONSES

Nadja Abt

When i first read Fichte’s novel Explosion: A Novel of Ethnography (1993), nearly three years ago, I had just arrived in São Paulo on a residency. Since then, I’ve never really left Brazil and the book’s protagonists, Jäcki and Irma, have followed me – or, rather, the other way around. In February 2017, I travelled by cargo ship from Hamburg to Santos, making a short film about the female seafarers on board, inspired by Fichte and Leonore Mau’s film The Day of a Casual Dock Worker (1966). Like Jäcki and Irma, I travelled to Portugal and photographed fishermen; I searched for the old cinemas they visited in Rio de Janeiro; and, when I was invited to do a performance in São Luís de Maranhão in Northern Brazil, I visited Casa das Minas – one of the temples of the syncretic religion Tambor de Mina – which Fichte and Mau documented in 1971 and 1982. Mau’s photographs still hang in the main hall.

Nadja Abt is an artist and literary scholar who lives and works in São Paulo, Brazil, and Berlin, Germany.

Philipp Gufler

Through Jäcki, his novelistic alter-ego, Fichte turned against the very thing that usually forms the centre of autobiography: his identity. ‘Why don’t you put your I in quotation marks!’ he wrote in On Puberty. ‘Call yourself novel.’ Jäcki blended ethnographic reports with radio features, interviews, descriptions of interactions and observations from Fichte’s life. Fichte questioned the pigeonholing of sexuality. Jäcki lived together with the photographer Irma as an open homosexual. Imitation is lifelong pubescence; it doesn’t aim to be authentic.

I’d read works by Fichte, such as The Leatherman Speaks with Hubert Fichte (1977), before I joined the self-organized archive forum homosexualität münchen (Munich Homosexuality Forum) in 2013, where I worked on the history and politics of AIDS in Bavaria. Jäcki never openly referred to his own affliction with AIDS. In Explosion, Fichte called it a ‘sublime, raucous cockatoo illness’.

For my 2017 exhibition ‘Orbiting of the Novel’ at BQ in Berlin, I imitated Jäcki’s exaggerations, gossip and slander: ‘Jäcki is for Jäckis,’ I wrote. ‘He was all cursives, posed. Jäcki exhibitionized.’ When the only mirrors are distorting mirrors, everything stays hidden. Jäcki couldn’t wear a fake costume because there wasn’t a single real one.

Philipp Gufler is an artist based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and Munich, Germany. In 2017, he had an exhibition at forum homosexualität, Munich; later this year, he will have a solo show at BQ, Berlin, Germany.

Ariane Müller

In Fichte’s On Puberty, 16-year-old Detlev observes the ‘safari suit’ of a man named Gerd Werner. Suddenly, ‘all the retained agony and lust float on waves of curaçao out into music chamber number 2: — Love you so, love you, you I love so, so, I love, love, love, you, so, so, so!’ These lines scrolled on an LED sign in ‘Fini, Fichte, black Flag’, an exhibition about Fichte and Leonor Fini that Dirk Bell and I put together at Galerie Amer Abbas, Vienna, in 2011. The two artists were contemporaries who could have met, but didn’t. Dirk showed paintings inspired by Fini in a wardrobe; I scribbled Fichte’s writings on furniture and, for the first time, displayed my Hubert Fichte Travel Library (2011): an IKEA bag filled with plaster and slipcases from 11 of Fichte’s books. In the dimly lit room, it looked like any normal IKEA bag; you wouldn’t guess that it was too heavy to move.

Ariane Müller is an artist and writer living in Berlin, Germany, and Vienna, Austria. She is co-publisher of Starship magazine. Her work is on view at Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin, and Oracle, Berlin, until 3 March.

Main image: Leonore Mau, Carnival, Trinidad, 1974, photograph. Courtesy: S. Fischer Stiftung