Ideal Syllabus

Andrew Durbin discusses the books that have influenced him

Andrew Durbin discusses the books that have influenced him

Robert Glück, Margery Kempe (1994)

A founding member of San Francisco’s New Narrative movement, Glück is a novelist and poet who often searches his personal life for its resemblance to other lives, other histories, other places. In Glück’s work, the autobiographical ‘I’ is usually bigger than it appears – a widening vortex that swallows the world whole, real Bob and all. In this novel, a love story between Bob and a younger photographer finds its historical echo in the life of the Christian mystic Margery Kempe, who wrote the first autobiography in English in the 1430s. A technical blitz of sex and gossip, Glück’s novel is poetry – shaped like fiction – for those who can’t talk to God, but don’t want to quit trying.

Trisha Low, The Compleat Purge (2013)

Beginning with a series of last wills, Low prepares for her many demises by making an inventory of her life, from her adolescence to her early 20s, assigning toys, credit cards and books to friends and loved ones. Low purges herself of desire, affectation, fandom (one section consists of transcripts of sex fantasies about indie rock stars), only to find that these pesky things always come back bigger, badder and stronger than before. It turns out that getting rid of your self requires a lot more than dying.

Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red Times Square Blue (1999)

The best, and most succinct, of Delany’s memoirs, Times Square is an intimate ethnography of New York’s least favourite, most-trafficked polygon. He traces the area from its height as the city’s centre for sex and cruising, at the various porn theatres and video stores that lined 42nd Street, to its downfall under the Giuliani administration. Delany is at his most perceptive when the historical and the personal come into close orbit. With this book, he finds in his own story a larger epic of blue New York, a place where bodies of many kinds and classes once found happiness (or financial relief) in one another, albeit briefly, on the corner of 42nd Street and 7th Avenue.

Chris Kraus, Video Green (2004)

I can’t think of a better book of cultural criticism, mostly because each essay moves fairly quickly beyond the matter at hand to much larger concerns: S&M sex, urban life, what it means to make art in California, to name a few. ‘Emotional Technologies’, my favourite essay, has guided me in all things since I first read it.

Eileen Myles, Chelsea Girls (1994)

I don’t know. That’s where I begin, and that’s where Myles’s rangy book begins, too: out in the open, with a narrator who’s a little lost, a little confused. Chelsea Girls changed my life, much in the way people say reading Marcel Proust changed their lives. (I’ve read Proust and, for sure, Myles’s work changed me more.) With swaggering prose that verges, brilliantly, on feeling totally off-the-cuff, this novel whispers in your ear, a little drunkenly. It asks you to come along for the ride, wherever you may be at that moment. I went with it and never came back.

Andrei Platonov, Dzhan (Soul, 1935)

In this dreamy Russian novella, an engineer heads east from Moscow to the Central Asian desert to help bring his former tribe of nomadic people into Soviet modernity. Stuck in the ‘hell of the whole world’, he fails and, in failing, Platonov’s protagonist not only offers a covert critique of the Soviet system (falling foul of the censors, the book wasn’t published in its entirety until 1999), but of colonialist ‘modernization’ projects in general. Shot through with mystical symbolism, Dzhan is also deeply concerned with weighty issues that remain current and very real today, from ecology to the legacy of slavery.

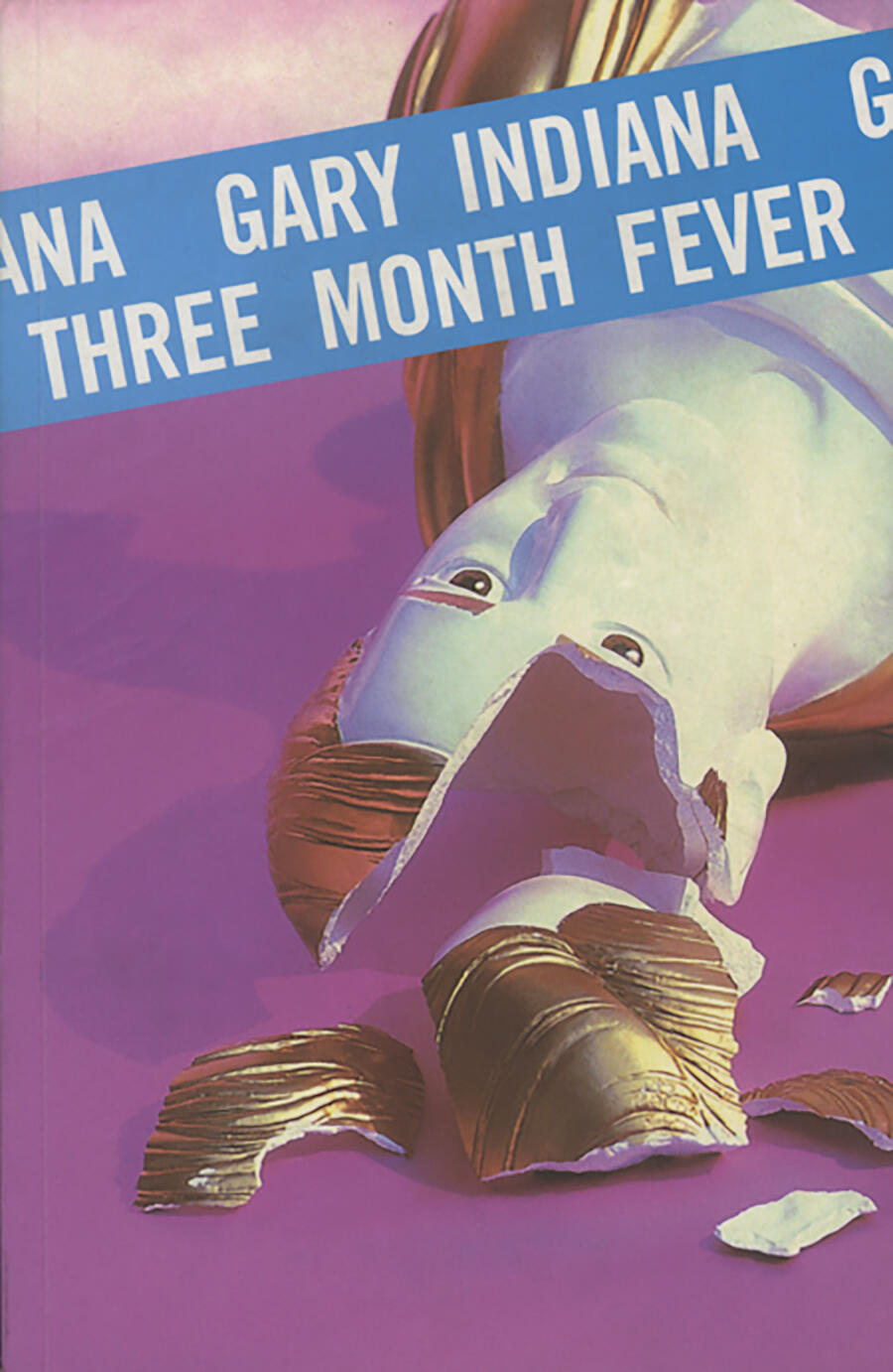

Gary Indiana, Three Month Fever (1999)

The second in Indiana’s informal true-crime trilogy, Three Month Fever hacks into the mind of serial killer Andrew Cunanan, infamous for murdering Gianni Versace on the steps of his mansion in South Beach, Miami. In doing so, Indiana reconstructs the warped psychology of a killer whose story the media, gripped by homophobic panic, largely got wrong. He follows Cunanan’s tortured path to his three-month killing spree in 1997: from his early years as a credit card-addicted, pathological liar in San Diego to his Midwestern rampage that ended gruesomely on a houseboat in Florida. In caustic, speedy prose, Indiana describes Cunanan’s descent into self-delusion and unfocused ambition (for money, for success, for love) as the two combined to lethal effect.

Dodie Bellamy, The Letters of Mina Harker (2004)

In this sequel to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Mina Harker (the wife of protagonist Jonathan Harker) finds herself in San Francisco in the 1980s, at the height of the AIDS crisis. It is both a nightmare and an account of the plague years. This epistolary novel follows Harker – in reality, the author – through various trials of love and friendship in a grim mediascape that she navigates with the aid of theory, poetry, fiction and sex. Bellamy’s letters struggle to make sense of a haunted world, forming a narrative that refuses to cohere along convenient or comfortable lines.

Abdellah Taia, L’armee du Salut (Salvation Army, 2006)

This semi-autobiographical novel follows the struggling narrator’s move from Morocco to Switzerland after he receives a scholarship to study in Geneva. On his journey, Abdellah strives to ‘discover’ himself in the differing contexts of the Arab world and Western Europe – societies that challenge his views and which he, in turn, challenges, particularly fear of homosexuality and the Other. Throughout this slim volume, the narrator renegotiates the terms of family, friendship and home. He does not achieve an easy peace (or salvation, for that matter), but it wasn’t ease he was seeking in the first place.

John Ashbery, Three Poems (1972)

Difficult to summarize, but I feel these poems, particularly ‘The System’, represent the best use of the English language since George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1872).