The Life and Times of Alexander McQueen

A tender new film about the fashion icon and troubled genius whose creative vision ‘started the 21st century’

A tender new film about the fashion icon and troubled genius whose creative vision ‘started the 21st century’

The stand-out garment from Alexander McQueen’s 1992 graduation show for his MA at Central St Martins, is a precisely proportioned dress coat, cut from a shot-pink silk satin. A black thorn print runs through it like the shadow of barbed wire. McQueen had been inspired, he acknowledged grimly, by Jack the Ripper’s Whitechapel murders of 1888. Installed at the record-breaking ‘Savage Beauty’ exhibition of McQueen’s work in New York at the Met in 2011 and in London at the V&A in 2015, it retains a diabolical elegance: arch, acerbic, sullen. It bears that characteristically McQueen-ish ambivalence. It is a dress-coat designed for a woman who could be both injured and injuring, scored by violence but sharpened by it too.

That coat features early on in Peter Ettedgui and Ian Bonhôte’s elegiac new film. McQueen (2018) borrows liberally from catwalk footage and home videos. The archive material is interspersed by interviews with friends and family and is set to a passionately tempestuous Michael Nyman score. As a result, it’s a film that cannot help but be beautiful and melancholic, its sadness rising like a tide as the story bends to its inexorable end. ‘I want to be the purveyor of a certain silhouette, a certain way of cutting,’ McQueen had declared, ‘so that when I am dead and gone people will know that the 21st century was started by Alexander McQueen.’ In the fashion industry, few would deny that McQueen’s astonishing creative vision did start the century and it is the cruellest irony that his suicide in 2010, aged just 40, meant that he would barely witness quite how profoundly he could shape it.

Ettedgui and Bonhôte’s film is burdened by the enduring grief of those McQueen left behind – a sister, a nephew, his friends and team, their pain often still palpable. But it’s also a film that is charged with a serious question: how could a talent like McQueen’s have come into being at all? There is a certain romance to this story. It is the rags to riches tale of an East End bad boy made good. He was a mischief-maker with an eye for provocative design, championed by style savant Isabella Blow and eventually ensconced in the elite house of Givenchy, before rebelliously breaking free of them both, determined to advance his independent vision. He was the industry’s incorrigible enfant terrible, a chubby, chain-smoking scapegrace, gleefully upturning haughty high fashion conventions, parading girls in gimp masks and slinking ‘bumsters’, setting cars alight next to collections staged in Victoria Coach Station.

The film plays up his journey, delighting in all its incongruities. The early interviews present a doughy-faced skinhead with buckteeth who jeeringly pronounces it ‘Ort Cutchure’ and stitches profanities into the linings of Savile Row suits. He cackles wickedly at the edges of the camera, a ‘hooligan with a needle’, running amok in backroom studios and elegant Parisian avenues. Ettedgui and Bonhôte make clear how deeply likeable he was, how extraordinary his gifts were, how brutal the fact of his suicide. How does a life like McQueen’s unravel? This is the film’s inevitable question, only guessed at: drugs, an HIV diagnosis, a history of childhood sexual abuse, the death of a beloved parent, exhaustion, unremitting loneliness? In the end, it is a mystery, of course. We are left, instead, with the enveloping darkness that is always intimated in the work. ‘I pull these horrors out of my soul and put it in my clothes’ he explains, almost nonchalantly, laughing in the dark.

At its best, the film allows those clothes to speak on his behalf. The camera lovingly lingers on a collar, a sleeve, a mask, as the garments slowly rotate in velvety darkness. The designs translate effortlessly to film and it is exhilarating to examine them so close up. If the backstage tomfoolery reveals McQueen’s process as ludic and ad-hoc sometimes, it is never, ever thoughtless. His low-slung ‘bumsters’, cheaply derided by the popular press, were, he explains, studiously deliberate, lowering the waist and breaking up the proportions of the body. The ‘Highland Rape’ collection of Autumn/Winter 1995–6, referred not to the rape of women but the plundering of Scotland by English colonizers in the 18th and 19th-centuries. The film gives him the space to patiently recount how urgently that history resonated, the 20th-century genocides of Rwanda and Bosnia pressing upon his mind.

This is a tender film about a troubled man, mostly told by the people who cared for him. It is often sorrowful and pained. To those who know the story, there are no great revelations. The film rehearses old grudges about the fallout with Blow and retells the tired controversies. But what emerges with brilliant clarity is the sheer miracle of McQueen and his unfathomable, inexplicable genius. ‘I wanted to learn everything’ he tell us at the beginning of the film, describing his early career as a tailor’s apprentice in Savile Row. ‘Give me everything’, he urged with the endless hunger of the autodidact. But everything isn’t always enough.

Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui’s McQueen (2018) is out now in select cinemas in the UK and is released in select theatres in the US on 20 July.

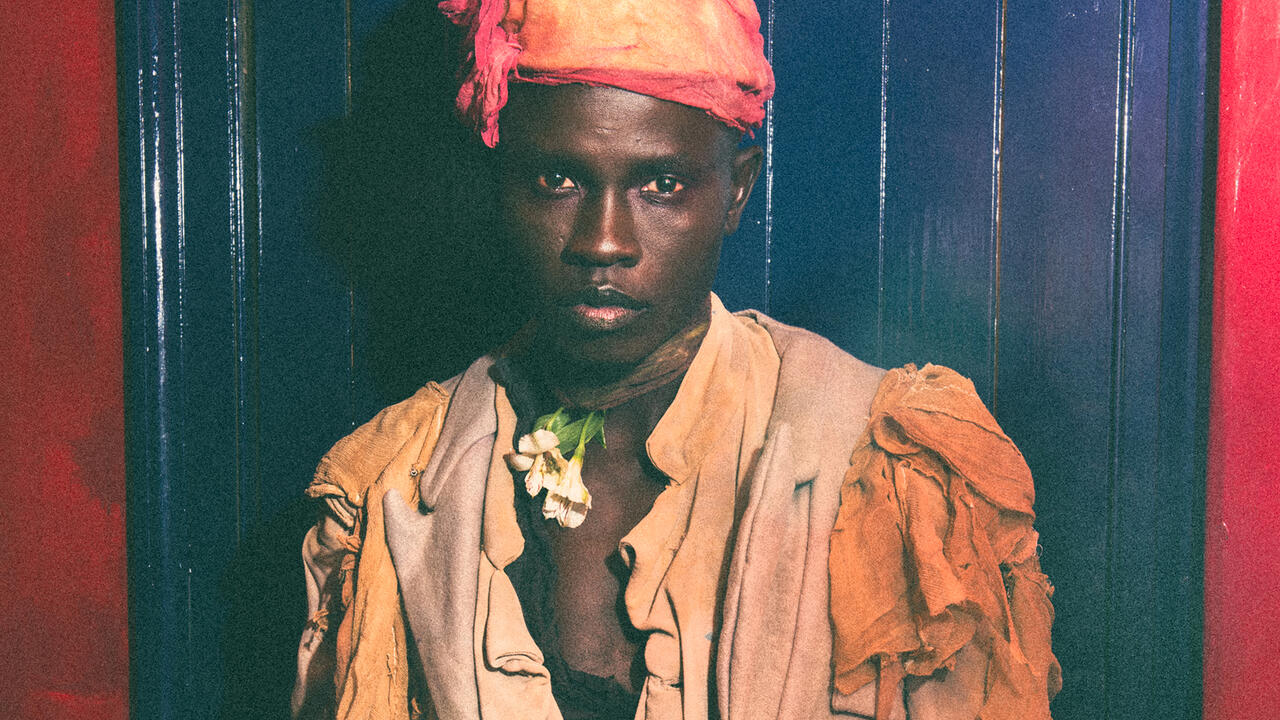

Main image: Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, McQueen, 2018, film still. Courtesy: Misfits Entertainment; original photograph: © Ann Ray