Life Repeated

Two films using time and repetition to question our fragile relationship to lived reality and revolutionary politics

Two films using time and repetition to question our fragile relationship to lived reality and revolutionary politics

‘First as tragedy, then as farce’ – so goes Karl Marx’s often quoted prediction that the worst of history is doomed to repeat itself. But what if repetitions of the past could actually be made to serve political progress? Such is the argument of Benedict Seymour’s new film Dead the Ends (2017) which premiered this month in the Experimenta section of the London Film Festival.

Seymour starts from the unpromising premise of adapting Chris Marker’s dystopian story of looped time, La Jetée (The Jetty, 1962). Set in a future Paris ravaged by nuclear war, Marker’s film follows a prisoner forced by the victors to travel back in time and recover resources for the present. Chosen for this mission because he is emotionally haunted by his past, the prisoner finds himself repeatedly returning to a traumatic incident from his childhood: a shooting he witnessed, which turns out to be the moment of his own death. It’s also about the relationship between film and memory, told through voiceover and mostly still images, and stuffed with enigmatic references to cinema history. Perhaps this focus on the medium is why the it has been endlessly imitated by artists, from Terry Gilliam in 12 Monkeys (1995) to David Bowie in the music video for Jump They Say (1993), begging the question: why do so again? In focusing instead on the political content of La Jetée, Seymour makes a more compelling case than most.

The key traumatic event in Dead the Ends is the real-life shooting of Mark Duggan, by London’s Metropolitan Police Force on 4 August 2011. The police initially stated that Duggan was armed – though no gun could be found and claims he behaved aggressively were disputed by eyewitnesses – triggering protests that he had been unfairly targeted for being black and working class, which escalated into five days of rioting and looting in cities across the UK. From this Seymour spins his own speculative time travel fiction but with a distinctly Marxist argument, in which this brief period of civil unrest becomes the pivotal moment in the emergence of a new revolutionary proletariat. In reading Marker through the UK riots, he suggests that we should raid the past to find material for a better political future.

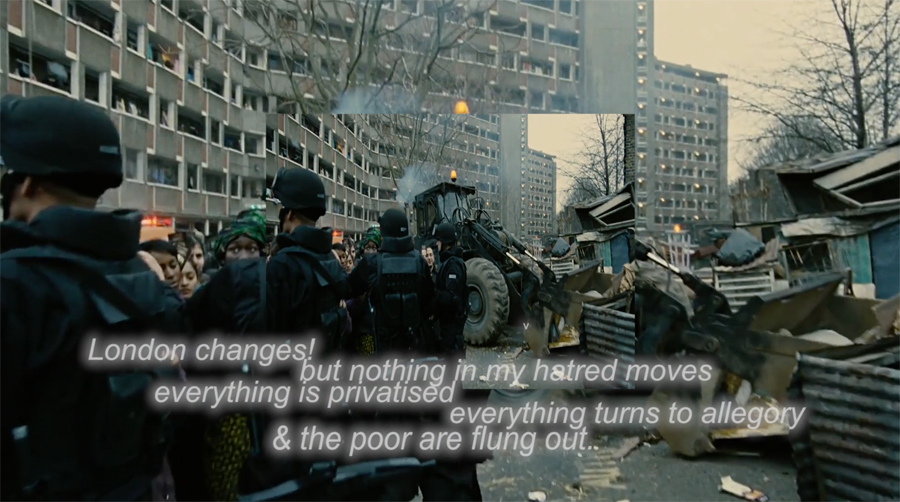

As in La Jetée the action in Dead the Ends is told through voiceover, but instead of stills it is illustrated by gifs – the better to insist on the repetitive nature of history. Mostly taken from recent films, these clips provide a witty genealogy of dystopian science fiction. While films from The Matrix (1999) to Children of Men (2006) speak of very real fears surrounding ecology, technology and government manipulation, Seymour shows that few – one example being V for Vendetta (2006) – offer depictions of collective political resistance. Dead the Ends also compellingly argues that looped time is far from the stuff of science fiction. Take the policy of racial profiling that has led to inordinate numbers of young working class black men being stopped and searched by police. This relies upon an anticipatory logic in which those targeted are always already guilty of a crime that will happen, but has not yet taken place – the very logic that apparently led to Duggan’s death.

The film loses its way towards the end where these observations are obscured by an overstretched thesis. It is never clear, for instance, why Duggan’s shooting has been singled out as historically significant over others, with no other class uprisings, such as those which followed the Greek debt crisis of 2007 or the Argentine Great Depression (1998–2002), being mentioned in the 30-year period covered. Far from bringing the promised race and class war, the riots soon petered out and were framed by the political establishment as merely indicative of isolated criminality and moral failing. This is perhaps part of Seymour’s point: leftist commentators too readily predict the downfall of capitalism at the slightest sign of civil unrest, but capital today is diffuse and such narratives of progress seem decidedly retro (he depicts the bombing the long defunct London fashion store Biba, based on the real event undertaken by left-wing radical group The Angry Brigade in 1971). But the film’s narrative becomes hemmed in by an exhausting accumulation of alienation techniques poached from Marxist cinema – periods of black screen, screen in screen framing, disjunctive sound and intertitles. If time travel in both Marker and Seymour’s films depends upon the protagonist’s emotional attachment to the past, it might have been wise to forgo these clever tricks so that viewers could connect with the footage and feel the political urgency of the realities depicted.

By contrast, the complex relationships between emotion, screen image and lived experience are the focus of Chen Zhou’s documentary Life Imitation (2017), which screened in the same section of the festival after collecting the New: Vision award at the CPH:DOX festival, Copenhagen, earlier this year. Entirely eschewing argument and linear progression, the film is instead organized around an atmosphere of pervasive, unrelenting malaise.

It opens with a close-up of a phone screen showing a text conversation conducted via Chinese social media app WeChat. A girl is discussing her conflicted relationship to her own sexual identity, in an apparent monologue, before a pair of hands startlingly emerge from behind the camera to type ‘I’m shooting. Please continue’. Cut to two of the director’s female friends in a Shanghai bar discussing the difficulties of lesbian relationships, particularly when you can’t afford your own apartment and have to live with your parents. Scenes of queer life in the city, documented in the streets or related through social media, are interspersed with extended footage from the video game Grand Theft Auto V, showing a lone female avatar apparently aimlessly stalking through empty streets. Conversations in this film are observed rather than participated in, plans are forever deferred, life is imitated rather than really lived.

A clip of one girl obsessively airbrushing the selfie she has just taken, and another crying hysterically because none of her WeChat friends have shown up to her party, suggest that genuine experience is being eroded by digital artifice, only for such glib conclusions to be undermined. Real-life encounters are no more natural: conversations are shown to be dominated by clichés and sexual stereotypes – in sex the ‘guy is still himself’ but women give themselves to their partners – and the few anxious outbursts feel staged. Even a basement gay club provides no release, the party-goers apparently isolated in a detached, drugged stupor. Throughout most of the film, the video game is shown on a television screen, with a pot plant visible next to it – a juxtaposition set up less to contrast the real and the virtual, than to show two types of imitated nature. Just as queer theorists have claimed that there is no real, natural gender, but rather that all identity is copied and performed, Zhou troubles the idea that there might be some authentic way of life that his friends are missing out on. The problem affecting both films may well be that the screen image promises a coherence in action and in subjectivity that just isn’t possible, and which, if we believe in it, risks distancing us from the emotional messiness of life itself.

Main image: Chen Zhou, Imitation Life, 2016, film still. Courtesy: BFI London Film Festival 2017