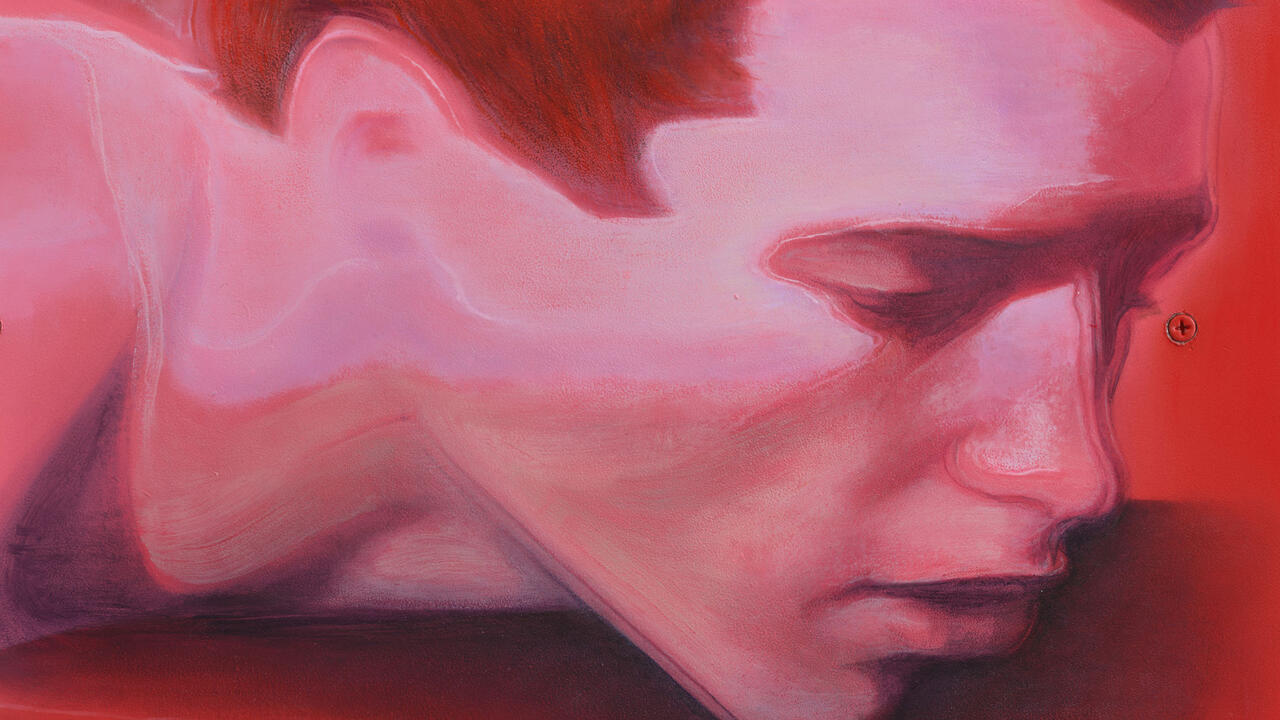

Light Source

Chinese video art, post-socialist trauma and the work of Cheng Ran

Chinese video art, post-socialist trauma and the work of Cheng Ran

A flock of pigeons nests in the rafters of an empty factory. Suddenly, the strip lighting is flicked on, the camera tilts and the birds burst apart in a frenzy at the neon glare. I love this moment in Cheng Ran’s Rock Dove (2009) – its cinematic language, the lens that catches the abrupt fracturing of a calm surface, and how it gets to the heart of the ways in which the social and temporal space of the artist’s motherland has itself been fractured.

Cheng Ran is the bright star of a surging generation of mainland Chinese artists working in video and lens-based media. Born in Inner Mongolia in 1981, he graduated from Hangzhou’s China Academy of Art in 2004. He spent five years as an assistant in the studio of prominent video artist Yang Fudong, absorbing Yang’s experiments with the perception of time and the nature of the spectator. This was the kind of work that, as Xiaoping Lin argued in his book Children of Marx and Coca-Cola (2009), articulated an ultimate ‘escape from a global nightmarish reality’. Cheng’s first video was 2005’s Light Source, in which a darkened door is cracked open to reveal a flickering bright light. The span of his artistic practice – deploying everything from Super 8 to mobile phone footage, as well as drawing on the disembodying effect of the internet – reflects a particularly new Chinese psychic mix.

Cheng experienced the rapid arrival and development of video art in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). From the late 1980s onward, technologies and new practices flooded into the country. Television steadily made its way into the Chinese family home, disrupting and reshaping everyday life, in both city and countryside, like no other medium before. Meanwhile, visiting lecturers introduced works by artists such as Matthew Barney, Gary Hill and Bill Viola to students at the Chinese Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing. China’s post-Cultural Revolution generation absorbed this new influx, but without the formal training that artists in the West received. Video art practice began to coalesce around a group of artists at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts who were keen to pursue a form that wasn’t so readily subject to the twin pressures of officialdom and commercialization. With such works holding little market value, and rarely attracting the attention of museums or individual collectors, they acquired a temporary respite from state censorship.

From its beginnings in ritualistic experiments in repetition (such as the 1988 work 30x30, by the father of Chinese video art Zhang Peili, in which he shatters a mirror, pieces together the fragments, then breaks it again, over the course of three hours), and then the avant-garde excess of the 1990s (for example, Xu Zhen’s 1998 I’m Not Asking for Anything, in which the artist swings a dead cat around a room for 45 minutes until the corpse is pulped), Chinese video art has swiftly shifted from crude recordings of performance art to more sophisticated reflections on the narrative form itself, pushing lighting, framing and temporality to their extremes. It has incorporated everything from the computer-game fantasies of Cao Fei’s RMB City (2007–11), built within the virtual world of Second Life, through to the fusion of animation and ink-wash in the smeared, steampunk vistas of Qiu Anxiong’s epic New Book of Mountains and Seas (2006). This is art that triumphantly anticipated its mediatization and digitization, while at the same time rejecting its complete institutionalization, with videos appearing in limited editions, underground art festivals and short-run exhibitions.

Amid this evolution, Cheng took clips from late-20th-century Hollywood films, anime, French New Wave cinema, Korean soap operas and wuxia Chinese warrior fiction, and treated them to small-cell repetition, loops and drones – defamiliarizing familiar scenes to the point at which they become hazy, dreamy. In his 2012 video 1971–2000, Cheng riffs on iconography from two pop-cultural staples: Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Wim Wenders’s The Million Dollar Hotel (2000). But Cheng’s interpretation of the kitsch and high-gloss of nostalgic Western cinema goes beyond his identity as a savvy cosmopolitan artist straddling the international art market. Cheng appropriates visual components and soundtracks from both films to create an entirely new video, including a character who blurs Kubrick’s Alex and Wenders’s Tom Tom, and which culminates in a flight off a rooftop. In doing so, Cheng’s hybrid video achieves an effect that is deeply impressionistic and trance-like.

If Cheng's predecessors watched as China's post-socialist project passed them by, his generation has been caught up in the mix, experiencing the aftershocks of the transition to capitalism.

In The Sorrows of Young Werther (2009, titled after Goethe’s eponymous 1774 novel), the artist films a forest at night, but he transforms it with the use of suspended mirrored balls and spinning lights that turn it into a dance floor with bursts of artificial colour. He dives deeper into visual somnambulism with his four-screen video Before Falling Asleep (2013), inspired by Aesop’s fables, setting up stilted conversations between actors playing two pigeons, a fire and a tree, a pond and river, a butterfly and a flower. The scenarios evince that moment known as hypnagogia, between wakefulness and sleep. It is this transitional state, often alluded to in Cheng’s work, that emerges at the intersection of his generation’s search for a cosmopolitan identity, in tandem with a changing awareness of space and time.

The seminal exhibition ‘Image and Phenomenon’ at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in 1996, curated by Qiu Zhijie and Wu Meichun, was the first show to theorize Chinese video as an art form. As Wu wrote, video ‘can expose reality boldly but it is also sensitive to imaginative impulses’. Consequently, she pinpointed the dual instincts that have guided Chinese video art: the grey zone between documentation and something much less concrete or tied to reality. Many of the mainland’s video artists have worked alongside China’s burgeoning independent documentary scene – a radical political movement that ‘with its aesthetics of spontaneity, immediacy and on-the-spot realism’, Ying Qian argued in the March 2012 issue of New Left Review, ‘has become one of the most vibrant spheres of artistic expression in the PRC, and a central forum for registering social change and critically depicting current realities.’

Though the way politics is reflected in cultural discourse has always been a profound marker of the limits of political imagination, is this really the only interpretative framework for artistic practice alive in the PRC? ‘You could say I shoot as the spirit moves me,’ Cheng remarked in 2011, in the Chinese art magazine LEAP. In this sense, Cheng aims to push past video art’s documentary spirit for what seems more like a strategy of disengagement. In his 2012 work The Sixth Angel for the Millennium, shot using a water tank – in reference to Viola’s 2001 Five Angels for the Millennium, in which angels rise up out of water towards heaven – Cheng reverses the process. As his angel is submerged in water, a team of rescuers break through the frame to drag him out. The character of the angel, the artist stated in a 2012 interview, asks ‘whether our end result should be spiritual or whether we should return to reality’.

Cheng’s work is indicative of the dual narratives that have gripped writing about contemporary Chinese art. The first is a story of struggle: artists frozen between the stances of ‘dissidence’ and ‘submission’ under authoritarianism. The second is speculative, rehashed commentary on the gold-rush fever burning through the Chinese art market. While both are no doubt valid discourses, neither brings a deeper understanding of what drives artists like Cheng. It could be that he and his peers are doing anything but succumbing to such simplistic binaries, especially as the focus of their work is on the digital and the moving image. Cheng works in media that are products of complex, globalized conditions, while simultaneously traversing a global art system. If Cheng’s predecessors watched as China’s post-socialist project passed them by, his generation has been caught up in the mix. They are experiencing the aftershocks of the transition to capitalism, a process that Slavoj Žižek describes as ‘necessarily painful’. And, in turn, their works are expressive of a post-socialist trauma, negotiating the relationship between visual and social transformation. In his 2013 video Joss, produced with the Parisian designer ITEM IDEM, imitation Chanel and Louis Vuitton bags are split apart by firecrackers; cardboard iPad cut-outs become engulfed in flames – joss paper for Chinese funerary rites in an age of globalized capitalism.

This socio-political transition has always been starker for those who, like Cheng, were born on China’s fringes rather than in its metropolises. The video artist Sun Xun, born in 1980 within China’s north-east rust belt, noted in a 2013 New York Times interview how the dominant ideology of his hometown was ‘that people in business were evil capitalists’. But when he moved to Hangzhou as a student, it turned out that ‘everyone was doing business’. This collective realization has provoked a turn in artistic practice towards the edges of post-socialist trauma, testing the limits of ‘the past in the present’, and the ways in which history, memory and time are always on the verge of creation and destruction. Sun explores this aggressively in his work, injecting his videos with references to muddled time and duplicitous official histories.

Cheng is an example of how China's youngest generation of video artists is demonstrating that as familiar vistas close, new ones open up.

Cheng has devoted his most recent work to more abstract ideas: the criss-crossing of geographical boundaries and, beneath this – whether on the page, the screen or beyond – he unravels the creation and deconstruction of the narrative form itself. The artist’s 2013 installation at Galerie Urs Meile in Beijing, ‘The Last Generation’, revolved around his novel Circadian Rhythm (also 2013). ‘City dwellers can never tell when exactly the daytime gives way to night,’ it reads, ‘they actually do not care.’ Across the gallery space, specific motifs from the novel materialized as objects: in Tide Conversations (2013), a collection of miniature scholar stones from Cheng’s travels were placed ‘in conversation’ with one another, and excerpts from the book emerged on train tickets and receipts picked up in Africa, Amsterdam and Iceland. Films featured in the show included The Last Sentence (2013), the product of Cheng’s work in Iceland, which involved cutting up panoramic shots on the road with dialogue from Gone with the Wind (1939) narrated by a Chinese couple. With parts of Circadian Rhythm’s text absent, all of these objects serve as memory capsules within the gallery space, orienteering the audience through the corridors of the artist’s gap-ridden topography.

Cheng’s solo exhibition last year at Galerie Urs Meile in Lucerne, ‘A Film in Progress’, drew on his reflections on the art of storytelling during a two-year residency at Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, working and reworking narrative and space. The installation revolved around the process of creating his nine-hour work, In Course of the Miraculous, a film with three plot strands, featuring the mountaineer George Mallory (who vanished while climbing Mount Everest), the artist Bas Jan Ader (who disappeared crossing the Atlantic) and the crew of the Shandong Lu Rong Yu fishing boat no. 2,682 (who were victims of a mass murder at sea). Cheng created additional artworks to trace the abstract process of filmmaking. Storyboard Film tracks his doodles and captures his murmurings on angles and editing, while Scenario Hypothesis showcases different lightboxes to demonstrate the artificial alteration of light in a collage of scenes. All these fragments hint at an abstract, kaleidoscopic potential in film creation.

Cheng is an example of how China’s younger generation of video artists is demonstrating that as familiar vistas close, new ones open up – and that the closure of political possibility does not necessarily correlate to the strangulation of human creativity. The fast-running waters of China’s socialist neo-liberalism inspire as they also impoverish. In Everything Has its Time (2011), Cheng makes a fractured mobile-phone recording of a busker on the Paris metro. ‘All of a sudden, the music echoed through the carriage and seemed to tear through the air and the people on board,’ he recalls in the accompanying programme note. But Cheng, caught in hesitation, had been too slow in capturing the opening of the tune. He tries to remember it, to re-create it, and then to loop it up with his incomplete recording. The moment is complete. And suddenly, his memory unlocks for us too.

Cheng Ran is an artist based in Hangzhou, China. His film In Course of the Miraculous debuted at the 14th Istanbul Biennale in 2015 and has its Asian premiere this month at the K11 Art Foundation in Hong Kong. Earlier this year, his work was included in the 8th Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions at Metropolitan Museum of Photography in Tokyo, Japan. A newly commissioned piece will be included in ‘A Beautiful Disorder’ at the Cass Sculpture Foundation in Sussex, UK, which opens in May 2016.