Liliana Porter's Sprawl of Toys Explores Labour

Featuring a new commission, the artist’s show at Dia Bridgehampton asks how viewing conditions and context shape perception

Featuring a new commission, the artist’s show at Dia Bridgehampton asks how viewing conditions and context shape perception

Liliana Porter rarely alters the found toys and figurines that comprise her extensive collection, viewing them as complete in their own right. Across the decades, the Buenos Aires-born, New York-based artist has staged these objects – often nostalgic mementos of mass production – in photographs, videos and large-scale assemblages. Her exhibition, ‘The Task’, at Dia Bridgehampton features this familiar cast – Elvis Presley busts, Mickey Mouse statuettes, porcelain dolls – alongside video documentation of her 2018 play, THEM, and significant photographic works from the 1970s, reaffirming the artist’s conviction that physical objects and their representations are equally ‘real’.

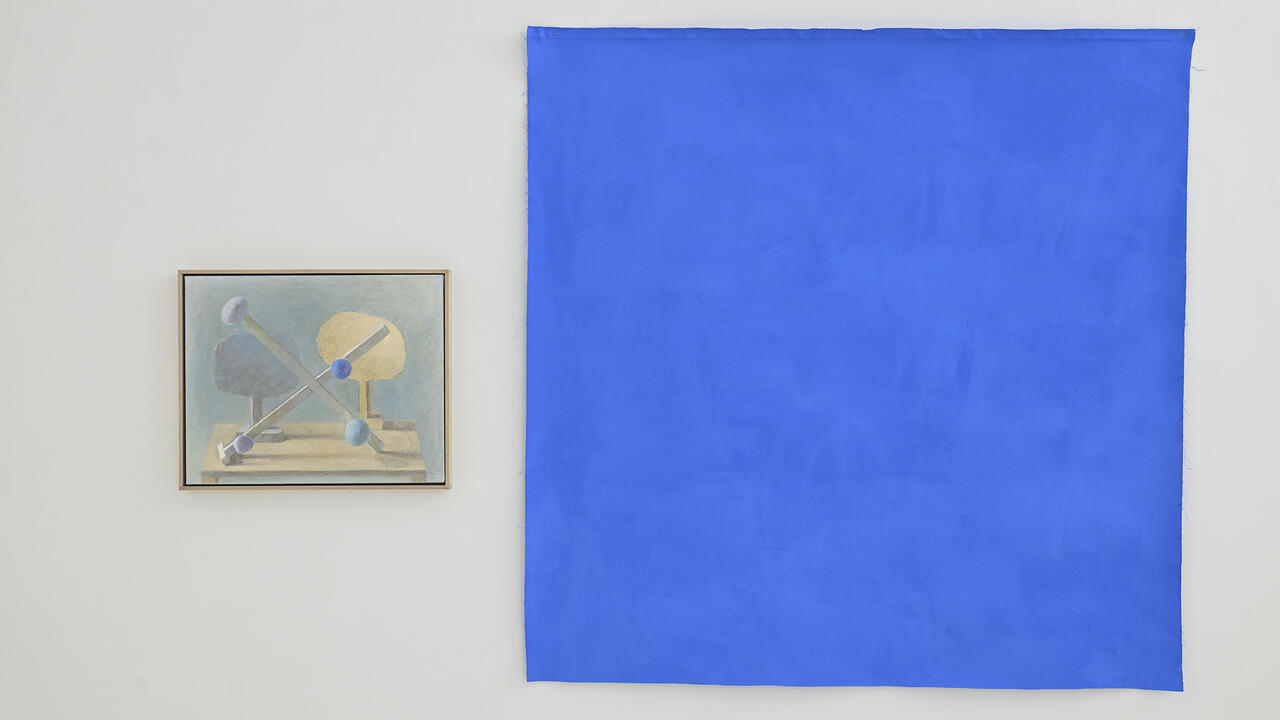

Sprawling across two plinths that line opposing gallery walls, The Task (2024) is the exhibition’s eponymous centrepiece. The new commission was conceived as an extension of Porter’s ‘Trabajo forzado’ (Forced Labour) series, begun in the 1990s, in which human miniatures confront colossal tasks. One tableau features a solitary figurine of an older woman knitting beneath a towering mass of pink tulle. Through the contrast between the minuscule figure and the vast expanse of the material, the piece visualizes a hyperbole, embodying the feeling of an interminable, gendered task. On a nearby vertical plinth, Geometric Shapes (1973) displays three small wooden shapes – a cube, a sphere and a cone – each illustrated with the drawn version of the shadow such a shape would naturally cast on its front face. Geometric forms recur in Untitled (geometric group) (1973), a wall installation comprising laminated gelatin silver prints modified with ink and graphite; precise lines extend from photographs of a cube, a pyramid and a sphere, signifying the presence of three imaginary plinths. Despite the disparate aesthetics of the pieces on view, which span nearly fifty years and range from minimalist to kitschy, Porter’s works maintain a conceptual continuity, relying on suggestion to draw attention to the interplay between form, perception and implied structure.

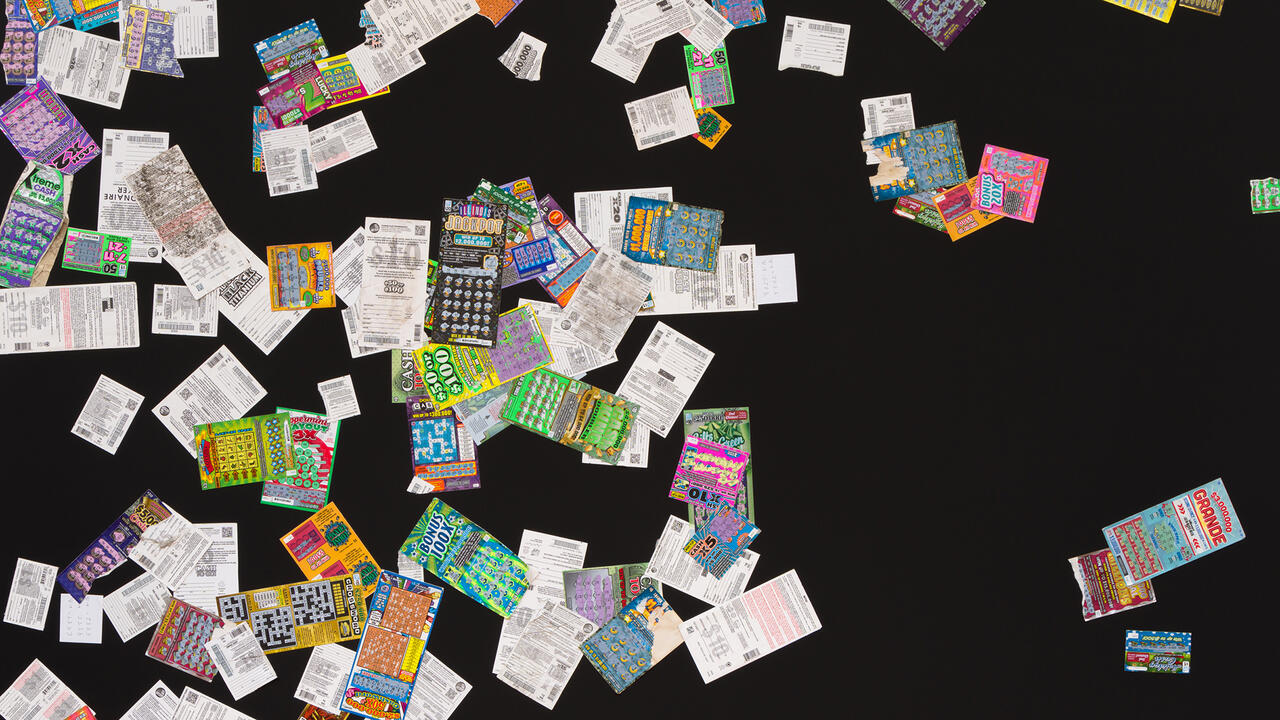

Another scene in The Task shows a small woman raking up a pile of shattered ceramics. From this central figure radiates a disordered assembly of vintage pocket watches, model train tracks, toy-sized mining tools and green army men: a trail of discarded symbols that once signified progress. Bordering on pandemonium, the display evokes the cinematic trope of a swirling vortex, displacing space and time. Positioning the viewer at a bird’s-eye perspective, the work prompts a reading of the fragmented situations as a historical gestalt – a kind of origin-story of modern labour. In the adjacent room, footage of THEM, originally presented at The Kitchen in New York, features disconnected vignettes in which actors address the audience directly. This presentation similarly underscores how our perception is shaped by specific viewing conditions and context – whether theatrical artifice or our role as ‘the spectator’.

The Task’s proliferation of objects features decommissioned Dan Flavin lightbulbs in orange and pink hues, which intersect with a broken chair precariously balanced atop a stack of vintage publications, including Donald Judd: Fifteen Works (1977). Judd, the father figure of American minimalism, argued that art should engage directly with the object rather than its representation, which extends to emotion or historical context. In contrast, Porter values both her objects’ physical properties and the viewer’s role in meaning-making. The inclusion of Judd’s exhibition catalogue in The Task is a tongue-in-cheek gesture. With its contents inaccessible, the book is reduced to mere signification; it becomes a shorthand for the complicated legacy of minimalism – a male-dominated movement that tended to dismiss the role of identity in artmaking and interpretation. Here, Porter transforms Judd’s ur-text of minimalism into one of the many tchotchkes that populate her installation, just a floor below Flavin’s permanent works at Dia Bridgehampton.

‘Liliana Porter: The Task’ is on view at Dia Bridgehampton, New York until 26 May 2025

Main image: Liliana Porter, The Task (detail), 2024. Courtesy: Dia Art Foundation and © Liliana Porter; photograph: Don Stahl