Music

A new work by jazz pioneer Anthony Braxton

A new work by jazz pioneer Anthony Braxton

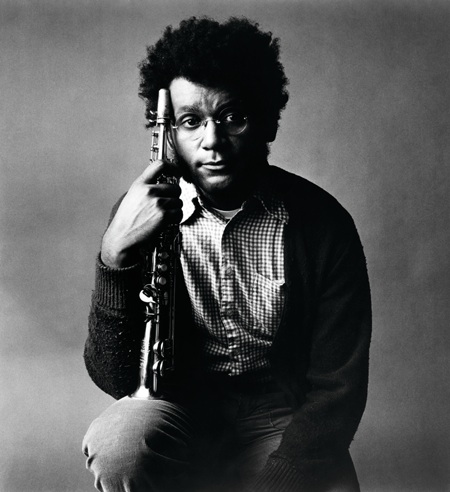

When composer, saxophonist and educator Anthony Braxton was named as a ‘Jazz Master’ by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) earlier this year, his acceptance speech at the award’s annual concert in Washington D.C. was generous, idiosyncratic and pointed. Generous in citing his inspirations, from contemporaries Joseph Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell to Johnny Mathis and the University of Michigan Marching Band. Idiosyncratic in its self-generated, though not entirely impenetrable, theoretical terminology: ‘When I think of the time-space of the 1960s, I think about the change from idiomatic to trans-idiomatic components.’ And pointed in questioning a verity of both the American Civil Rights movement and the branch of jazz with which it, and he, is most associated. He described an improvised solo saxophone concert early in his career: ‘I came to that with the understanding, “Oh! Freedom, freedom! Free at last!” After five minutes, freedom wasn’t working.’

Braxton’s allusion to Martin Luther King’s famous peroration shouldn’t be taken to mean he opposes the broadly egalitarian goals it reflects. For Braxton, the correspondence between freedom’s political and artistic meanings has never been as simple as it seemed to some in the late 1960s, when the musician, now 69, first appeared on the jazz scene as a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a collective of African-American players and composers that also nurtured the Art Ensemble of Chicago among many others. The AACM’s varied, sometimes cerebral approach was audibly distinct from the sounds coming out of New York around the same time, which equated the absence of structure with direct expression and an essential ‘blackness’. (This, at least, was the interpretation handed down through Amiri Baraka’s fiery critical writing.) Braxton distanced himself early on from Afrocentric interpretations of his music and its political implications, and much of his work since has combined traditional and graphic notation with improvisational techniques partly based on his own vocabulary as a soloist. This stance has often left him stranded between critics to whom all this music sounds like ‘free jazz’ and those suspicious of his acknowledged debt to the European avant-garde.

Unlike fellow honorees Jamey Aebersold, Keith Jarrett and Richard Davis, Braxton did not play during the NEA concert, instead giving the stage over to Ann Rose and Vince Vincent for a scene from his opera Trillium J (The Non-Unconfessionables) (2014), backed by trumpeter Taylor Ho Bynum, saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock and guitarist Mary Halvorson. The scene, a dialogue between a Civil War-era Southern belle (‘Scarlett’, lest we miss the point) and a visiting colonel seeking her hand and her land, was set in a highly chromatic, anti-lyrical style not too distant from the vocal writing of Alban Berg. Braxton’s libretto mixed hackneyed references to magnolia blossoms with anachronistic ones to nuclear arsenals and rapid-fire bursts of abstraction: ‘The concept of Affinity Insight Number Two is not separate from the components of experience and change.’ In the end, the pair join forces – economically no less than matrimonially – to remake the South in their own image. The singers’ vocal production was decidedly ‘classical’, while the spare, mordant music referenced jazz mainly in the horn players’ extended techniques and the astringent tone of Halvorson’s hollow-body Gibson guitar.

The scene was an uneasy meditation on the US’s plantation-era past, with something of the wit and measured rage of a Kara Walker diorama. Inevitably, it was only a partial guide to Trillium J, which is, in turn, only one segment of Braxton’s yet-to-be-completed ‘opera complex’ of 36 acts. The four-act, three-hour work premiered in New York this April at Roulette, a respected non-profit venue for experimental music and dance, as part of a six-night festival that also presented Braxton’s current ensembles, older compositions and guest artists under the aegis of his own Tri-Centric Foundation. Trillium J is anything but modest in scale: roles for 12 singers weave through a score for 37 musicians; dance sequences and video projections complete the picture.

Ambitious presentations of this kind have been something of a vindication for Braxton. Arista Records, who he was signed to in the late 1970s, funded orchestral and electronic recordings alongside more marketable jazz quartet albums. Later work in this vein, however, has been underserved by the American and European specialist imprints that have released a daunting array of solo, duo and small-group recordings. Braxton has also been fortunate in receiving support through a well-timed MacArthur Fellowship in 1994 and a tenured position at Wesleyan University. Several former students are now significant composers in their own right, but many continue to work with him. Bynum – Braxton’s co-conductor at Roulette – has emerged as a favoured lieutenant, and Braxton’s ability to call on a loyal pool of players familiar with his techniques has been crucial to the realization of works like TrilliumJ.

The plantation scene from the NEA concert was only a brief segment of the episodic first act. Scarlett and the colonel never reappeared; other scenes pursued related themes of power, social organization and technological change. There was even a square dance to jug-band music, one of the opera’s few recognizable vernacular references. The libretto’s curious, code-switching idiom is nothing if not consistent, with appeals to ‘the concept of Affinity Insight Number Two’ breaking the narrative frame at regular intervals, always completed by tangled, quasi-futurist doublespeak. In Act Two, a tableau of singers dressed as forest creatures – beaver, rabbit, frog – are banished from what the programme notes identify as ‘a depressed Midwestern town’ on assorted charges of corruption; in the next, greedy individuals assemble for the reading of a millionaire’s will, only to be murdered one by one.

This is not quite the high dramaone might expect of a contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk. Recent interviews suggest that Braxton has adopted stock situations to provide an accessible through-line alongside the demands of the music itself. The result is that the paper-thin characterizations and B-movie plots make Trillium J easy to follow but difficult to engage with.

In this respect, the work’s theatrical precedents are less Berg, Richard Wagner or even Karlheinz Stockhausen than the didactic flatness of Bertolt Brecht and Hanns Eisler’s Lehrstück. This was clearest in the two intentionally repetitive scenes that comprised Act Four. In one, a group of gangsters tortures one of its number for foolhardy excesses involving the deaths of bystanders and threats to public safety; in the other, a woman on trial for plotting to kill her husband defends herself against incontrovertible evidence. In each, a detailed litany of criminal excesses leads to no real admission of responsibility; both end inconclusively.

There was a leavening interlude – a joyous demonstration of jump-rope tricks by local teenagers – but the major characters, as in previous acts, were venal and self-regarding, and their accusers were not much better. As a long-time Braxton listener, I’ll admit to surprise at the work’s grim tone. I have always heard his instrumental groups, including those I heard the same weekend, as modelling a positive vision, not of unconditioned ‘freedom’ but of responsiveness and collective creation. Perhaps his rogue’s gallery of ‘non-unconfessionables’ references the half-monstrous masters of our financial, judicial and technological lives. Their unchecked reign is not among ‘the possibilities of the next time-cycle’ their creator might like to imagine, but it is the one he is presenting – at least for now. Four other segments of Braxton’s ‘opera complex’ have been staged or recorded, but many acts remain to be written.