The Must-See Exhibitions in New York This Autumn

As galleries return from summer break with a full slate of programming, here are the best shows in town

As galleries return from summer break with a full slate of programming, here are the best shows in town

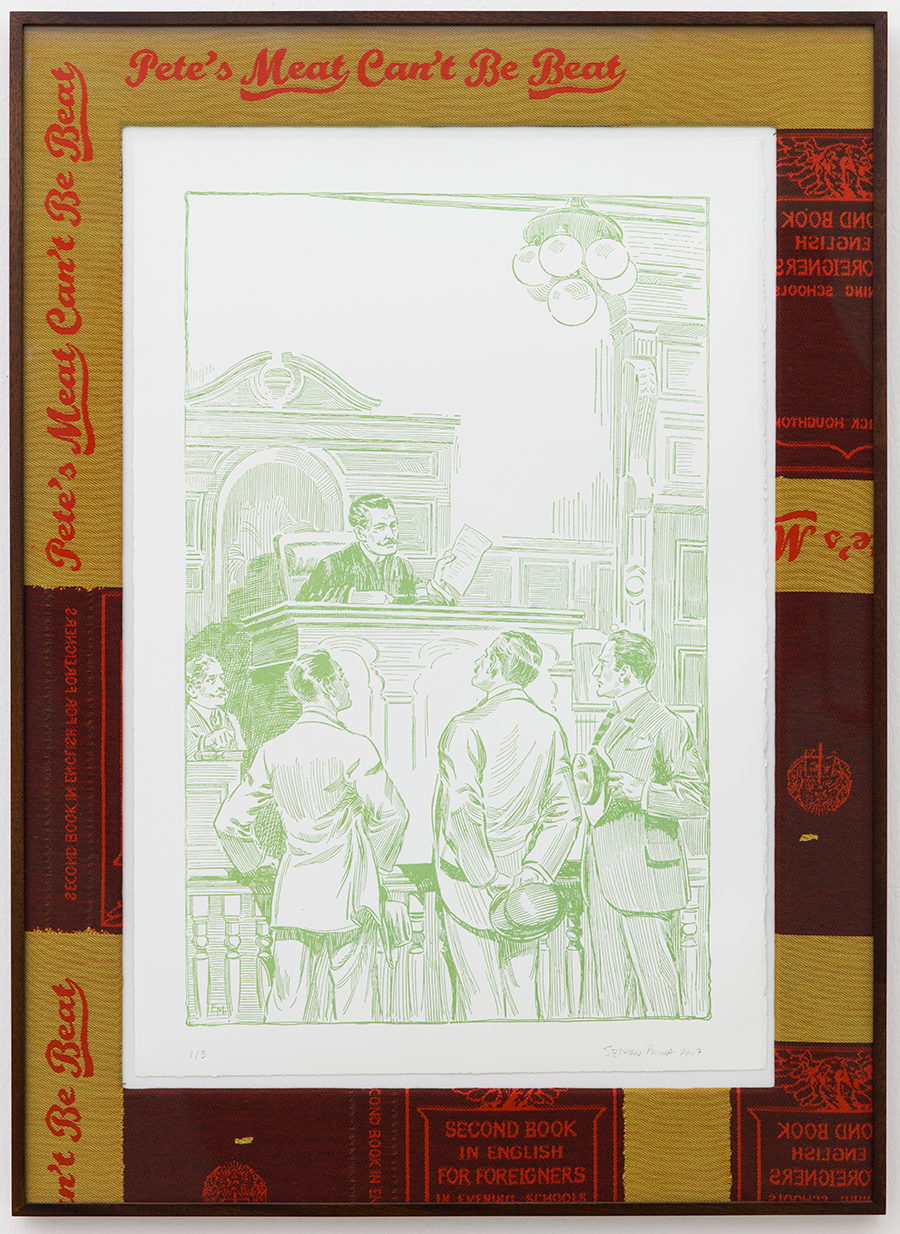

Stephen Prina, ‘English for Foreigners (abridged)’

Petzel

12 September – 26 October

The core of Stephen Prina’s exhibition at Petzel on 67th Street is a book without words. ‘English for Foreigners (abridged)’ (2017), the titular series of lithographs, assembles the illustrations from an eponymous 1917 book that the artist’s father bought when he arrived in New York from Italy in 1923. Stripped of text, the anodyne graphics are oddly unsettling. Dick and Jane skip past picket fences; a woman tends a wood-burning oven; a group of labourers dig a ditch. Each page is set in a wide, carefully embroidered frame with the slogan of the butcher shop Prina’s father owned: ‘Pete’s Meat Can’t Be Beat.’ (Pete evidently didn’t get the ribald joke.) The dopey polka that plays in the gallery, Giovinezza (Youth, 1909) scored for clarinet, was the anthem of the Italian Fascist Party, which Prina’s father, a clarinettist, conscientiously refused to play. (The brown and red upholstery that bears the slogan recalls the uniforms of Adolf Hitler’s Sturmabteilung.) The pairing winks at homosexuality’s long, fraught flirtation with fascism and the phallic instrument Prina’s father did beat; but it’s also a wry perversion of anti-immigrant, Anglo-American masculinity and prurience. There are familiar locations included in the lithographs: the old NYPD headquarters on Centre Street; the municipal courts further downtown. Cops and judges turn this innocent guidebook into a prep course for a life of disenfranchisement in the US judicial system. Such paternalism is an unhappy correlative to the xenophobia we’ve apparently never gotten over. Let’s hope that in 2020 we can finally beat it.

Leslie Hewitt, ‘Reading Room’

Perrotin

11 September – 26 October

Meaning is often elusive in Leslie Hewitt’s highly conceptual photographic and sculptural practice. It’s wryly appropriate that the spines of the paperback books she’s photographed for ‘Reading Room’, her first solo show at Perrotin, have been turned away from us to face the wall. Photographed on the floor of her studio, the books prop up square elmwood panels that, against the pale plaster, read as a study in whiteness. The photographs are printed on aluminium and rest in elmwood boxes that lean against the gallery walls – a formal doubling that also creates an uncanny trompe l’oeil. Several of Hewitt’s signature steel sculptures are scattered across the gallery floor like sheets of paper, reinforcing the sense of minimalist constraint. Then, Hewitt offers us a clue: two titles peeking out from a book stack, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Black Orpheus (1952) and Henry Dumas’s The Ark of Bones (1974). This is an archive of Black brilliance that demands to be read on its own terms.

Veronica Ryan, ‘The Weather Inside’

Paula Cooper Gallery

7 September – 12 October

In the summer of 1995, the Soufrière Hills volcano erupted, burying Plymouth, the capital of Montserrat, under more than 12 metres of mud. Artist Veronica Ryan had left the island many years earlier, when she moved to London at the age of six, but its fragile ecology remains central to her practice. The sculptures in ‘The Weather Inside’ seem either fished from the sea or fashioned from its flotsam, just as tides slowly swallow Montserrat’s shores. A row of razor clams rests beside an orange peel sewn back together, in possible homage to artist Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (1992–97). Charred seeds bundled in nets woven from plastic vegetable bags sit in a Styrofoam takeaway tray; above them, a small quilt embroidered with the words ‘weather report’ features a spiral of arrows like the eye of a hurricane or trash gyre. Ryan has placed these precious objects on metal shelves painted a bright safety orange, like specimens in a marine biologist’s lab. The artist burrows through the hard, toxic material of human life, from concrete-clogged pipes to crocheted holes in stacks of fuzzy avocado trays. Like hermit crabs sheltered in bottle caps, these precious sculptures find resilience in reuse as they grapple with environmental catastrophe.

Allora & Calzadilla, ‘Cadastre’

Gladstone Gallery

13 September – 2 November

An electric shock of yellow covers the dark, slick floor of Gladstone Gallery on 21st Street. Thousands of flowers from the araguaney tree, a species native to South America and the Caribbean, seem to have been shaken from their branches by a storm – or, perhaps, the hurricanes that have devastated Puerto Rico, where Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla are based. But these flowers will not fade: constructed meticulously of plastic, they seem also to refer to the loss of biodiversity wrought by climate change. When Hurricane Maria tore through San Juan in September 2017, it took weeks to get the power up and running, so the artists have sent a current of electricity through Cadastre (2019), the show’s title work – a 21-metre canvas piled with iron shavings. The current dragged the shavings across its surface, creating an elegant abstraction that, from a certain angle, resembles water damage (and the black mould that comes with it). Adding to this unsettling effect, a score by composer David Lang uses two notes on a violin to produce ‘shadow’ or combination tones, notes heard erroneously by the distortions of the inner ear.

Suh Seung-Won, ‘Early Works: 1960s-1980s’

Tina Kim Gallery

5 September – 12 October

Suh Seung-Won is a Zelig of Korean modern art: at various times, during his six-decade career, he has been a leading figure of Dansaekhwa and a founder of the ‘Origin’ group of hard-edged abstract painters. Little known in the US, his work seems long overdue for a retrospective here. This elegant show, which features paintings from the 1960s through to the ’80s, tracks Suh’s work from early, rough-edged minimalist forms in bright hues to later compositions in neutral tones, precisely layered and sanded. Suh began this later series when struck by the angle of moonlight cast through a traditional paper screen door; against the sea-blue of the gallery’s walls, the paintings’ luminous rhombi, obliquely projected, have a sense of suspended animation or oceanic drift.

Aliza Nisenbaum, ‘Coreografías’

Anton Kern

13 September – 2 November

Aliza Nisenbaum began painting portraits in 2013 while volunteering at Immigrant Movement International, a Queens-based organization founded by artist Tania Bruguera. Nisenbaum’s work studiously engages with community, particularly the bonds between activists, lovers and friends. Here, she began with portraits of salsa dancers she met at Gonzalez y Gonzalez, a downtown Manhattan club, whose exaggerated body language, lit by disco strobes, lends the paintings an ambitious dynamism and light that marks new territory for the artist. The show also includes her monumental London Underground: Brixton Station and Victoria Line Staff (2019), a portrait of Transport for London workers that now lives as a mosaic in the titular Tube stop. It faces another epic group portrait of workers from a very different class: the staff of Anton Kern Gallery, posed in the gallery’s storage facility, with paintings by Ellen Berkenblit, Brian Calvin and Chris Martin peeking through. Although these works are governed by a more staid set of the ‘Coreografías’ (Choreographies) of the show’s title, the subjects’ pathos could only be captured by someone who knows them well. If, at times, Nisenbaum’s looser brushwork recalls Alice Neel’s, these faces’ fractals of radiant colour are uniquely her own.

Paloma Bosquê, ‘In the Hot Sun of a Christmas Day’

Mendes Wood DM

10 September – 19 October

The title of Paloma Bosquê’s first solo presentation in New York was cribbed from a 1971 Caetano Veloso song that the Brazilian musician wrote while living in London, in exile from the military dictatorship. It’s a defiant love letter to the contradictions of a Southern Hemisphere Santa Claus, dressed in fur for summer heat. The show is accordingly filled with what the São Paulo-based sculptor calls little ‘displacements’, both spatial and material: paper sedimented like stone, lead strips that seem light and airy. Several works incorporate a chalky dental plaster and caramel-coloured rosin, like something that might get stuck in your teeth. Stars abound, with one metallic sphere hanging like a pendulum from a paper stack, and another cradled by the arms of an enormous wishbone (or tuning fork). The titular work, a pair of slender black columns installed on a floor of iridescent mirrored tiles that shift from warm to cool hues, left me with a floating feeling, as though I had been lifted into the cold, thin air near the sun, almost close enough to burn.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, ‘strings that show the wind’

JTT

8 September – 27 October

Elaine Cameron-Weir seems haunted by medieval ghosts. Her elaborate chain-mail constructions – shot through with wires, neon tubing and stainless-steel bars – resemble bionic re-animations of the bodies fished from Nordic peat bogs. Her solo show at JTT, ‘strings that show the wind’, likewise jolts Dark Age materials with an electric current. Most striking is the gallery floor, a clacking grid of steel tiles used to funnel wires in server farms. The titular ‘strings’ might be cables anchored in chunks of polished green fluorite, lifting up chain-mail standards emblazoned with fossils of the Anthropocene: medallions cast from seashells and what look like chunky earrings. Two steel trolleys hold concrete drapes ruched to resemble fireballs, fretted in cold white neon; at their centres, a floodlight lens glows faintly from paraffin candles burning beneath the mottled glass. If unearthed in a thousand years, this alchemical combination should prove just as fascinating and mysterious as it does here.

Longlist:

Lucas Arruda, ‘Deserto-Modelo’, David Zwirner, 12 September – 26 October

Raúl de Nieves, ‘As Far As UUU Take Me’, Company Gallery, 11 September – 20 October

Key Hiraga, ‘Works 1958-1993’, Ortuzar Projects, 6 September – 9 November

Loló Soldevilla, ‘Constructing Her Universe’, Sean Kelly, 6 September – 19 October

Loie Holowell, ‘Plumb Line’, Pace, 14 September – 19 October

Main image: Aliza Nisenbaum, Patricia and I Boogie on Broadway (detail), 2019, oil on linen, 2 × 1.6 m. Courtesy: © Aliza Nisenbaum and Anton Kern Gallery, New York