Nan Goldin on Why the Art World Must Shun Sackler Money

As leading arts institutions decline donations over opioid links, the artist and activist on why the age of using culture for ‘reputation laundering’ is over

As leading arts institutions decline donations over opioid links, the artist and activist on why the age of using culture for ‘reputation laundering’ is over

‘I don’t know how many righteous philanthropists there are, but some are darker than others.’ Artist and anti-opioid activist Nan Goldin is reflecting on the nature of arts philanthropy in a week that has given her a lot to think about and plenty to celebrate. Since London’s National Portrait Gallery announced on 19 March that it was declining a GBP£1 million grant from the Sackler Trust, several high-profile institutions in the UK and US have said that they too will no longer take money from the family whose wealth stems from Purdue Pharma, the US drug company that makes the highly addictive prescription painkiller, OxyContin. Tate, the Guggenheim – it’s a list that looks set to grow, as the US opioid crisis continues to take lives and Purdue faces a raft of law suits in the US.

In response, on Monday the Sackler Trust in the UK announced that it was suspending ‘all new philanthropic giving, while still honouring existing commitments’, stating that the attention generated by the US legal cases is distracting the organizations it funds ‘from the important work that they do’. For Goldin, the move is a clear case of saving face: ‘It’s like saying, I’m going to quit before you fire me. They know that it’s going to have a domino effect – what happened with the National Portrait Gallery, Tate, the Guggenheim – and they’re sure that other people will hold them accountable.’

As more organizations state that they have either given back (South London Gallery recently announced that it returned GBP£125,000 last year) or will no longer be taking money from the Sacklers, this feels like a significant moment for cultural sponsorship and the relationship between the arts and big business. There have already been signs of a changing landscape, with last year for example seeing Shell end its sponsorship deals with the National Gallery in London and Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, after years of protests over oil sponsorship and the arts. Meanwhile, earlier this week it was announced that Indian company Tata had pulled its sponsorship of the Hay Festival, a deal long criticized by Booker Prize-winning author Arundhati Roy who refused to appear at the festival while Tata was associated with it.

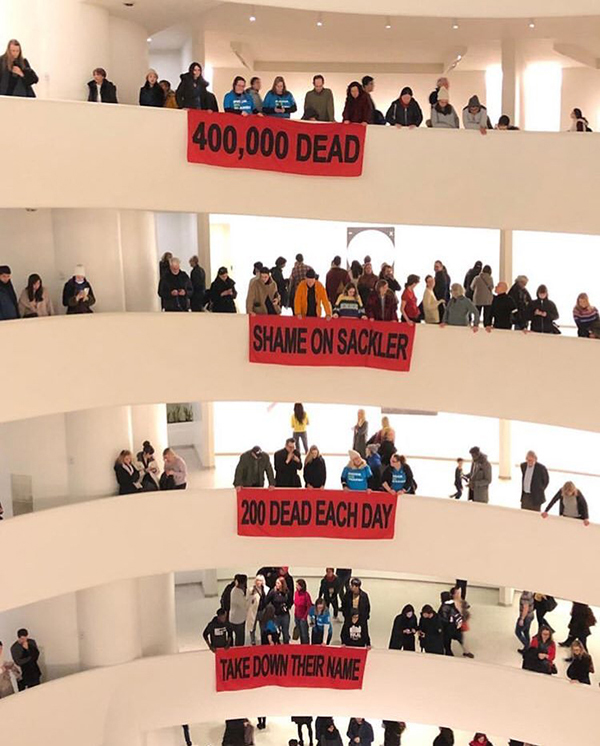

Goldin founded the campaign group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) with the specific aim of joining the dots between the opioid crisis and the Sackler name that graces so many cultural venues. The group’s principal tactic is direct action, including such spectacular interventions as this February’s protest at New York’s Guggenheim which saw thousands of fake prescriptions dropped into the museum’s atrium. But while its target is very specific, P.A.I.N. is clearly part of a much wider movement which refuses to accept that cultural organizations can remain neutral when it comes to the actions of their donors.

‘I grew up with the Sackler name in museums,’ says Goldin, ‘and I always thought of them with a smile, as big philanthropists.’ Now, after her own battle against OxyContin addiction and researching the source of that philanthropy, she believes that using the arts for ‘reputation laundering’ is becoming less and less viable: ‘There’s a demand for accountability and visibility now and so you can’t operate in the same way.’ She believes, too, that the growth in direct action, and the existence of other cultural campaigning groups such as Decolonize This Place, are all part of a wider shift: ‘There’s a surge of people fighting back against immorality. These times are so dark, so we have to fight against something, we have to pick our fight. And I picked this fight because I was an opioid addict myself.’

Not everyone in the arts views the impact of Goldin’s campaigning as a positive thing. Speaking to BBC Radio 4, former rector of the Royal College of Art Christopher Frayling described the Sackler Trust’s announcement as ‘a very sad day for the arts’ and expressed concerns about ‘a sort of moral panic in the arts world where lines are drawn’. While Frayling is clearly thinking about the interests of arts organizations and their increasing reliance on private funding – rather than the egos of billionaire philanthropists – it’s Goldin who seems to sum up the prevailing mood: ‘Museums are supposed to be repositories of beauty and learning,’ she says. ‘I hold them and art to a higher standard.’

Main image: Nan Goldin, Harvard Art Museums, 2018. Courtesy: Getty Images; photograph: Erin Clark