A New Museum Seeks to Make Texas a Centre of Contemporary Art

Ruby City resembles an edifice of red Texas rock; inside, the museum is airy, white and church-like

Ruby City resembles an edifice of red Texas rock; inside, the museum is airy, white and church-like

I did not expect San Antonio, in southeast Texas, USA, to be cold in October. Upon packing, I cavalierly ignored the weather forecast, knowing in my soul that I was headed for more temperate climes. So, at the outdoor reception for the opening of the late Linda Pace’s glorious jewel box of a private museum, designed by Sir David Adjaye and whimsically dubbed ‘Ruby City’, I found myself shivering in my shirtsleeves, buffeted by the powerful prairie winds. Yes, I was laughed at by my compatriots in the press, who had the foresight to wear their jackets to the airport. Yes, I drank entirely too much free mescal, in a futile effort to thaw my bones. But save for the slightly uncomfortable looking DJ who was installed near the museum’s entrance, spinning vinyl in a chunky scarf, the evening’s inclement weather didn’t put a damper on the festivities, which were the culmination of more than a decade of dreaming, striving and setbacks.

Beginning in 1993, Linda Pace established herself as a cornerstone of the San Antonio art scene by overseeing a residency program called Artpace, which brought a steady stream of up-and-coming talent whose work would become the foundation of her collection. Among these initial Texas pilgrims were some of the era’s luminaries, including Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Glenn Ligon and Tracey Moffatt. But perhaps most important to Pace – and germane to the building of Ruby City – was the affable, charismatic filmmaker Isaac Julien, who was an Artpace resident in 1999. By Julien’s own account, he and Pace became fast friends, with Pace collecting his work in considerable depth. ‘Being an artist at Artpace changed my life,’ Julien said during a talk with Adjaye the day after the opening, ‘and meeting Linda changed my life.’ Pace’s life was changed as well, along with the fabric of San Antonio: when she first entertained the idea of building a museum for her collection in 2006, it was Julien who introduced her to Adjaye.

Part of Ruby City’s charming lore is that the initial idea came to Pace in a dream, from which she awoke and sketched a glittering metropolis resembling a red-hued version of the Emerald City from the Wizard of Oz (1939), or (to keep it arty) one of Mike Kelley’s cast glass cities from his ‘Kandors’ series. Adjaye’s final building, unsurprisingly, bears little resemblance to this initial sketch, but it is enchanting nonetheless. The building’s ruddy concrete exterior, which appears imposing and bunker-like from certain angles and like exquisitely folded origami from others, glitters when hit by the sun thanks to thousands of shards of embedded glass. It resembles an edifice of red Texas rock, the kind that towers over the Palo Duro Canyon to the north. Inside, however, the museum is airy, white and church-like, with high ceilings and clerestory windows that bathe the main gallery in natural light. Adjaye, in his talk with Julien, explained that he thought of the structure as inherently spiritual, with the exterior relating to a ‘pagan’, nature-worshiping tradition, and the interior to a spirit-focused monotheism; he described it as a ‘marriage of the earth and the light’.

This emphasis on the spiritual seemed melancholically apt. Pace, after all, was not present to see the unveiling of her museum, as she died after a swift battle with cancer the same year that it was commissioned. Tragically, the president of the Linda Pace Foundation, Rick Moore, who had navigated Pace’s project though the rough seas of the 2008 financial crisis and delivered her vision to the city, also recently lost his battle with cancer, less than a week before the building’s opening.

The museum’s inaugural exhibition, curated by Kathryn Kanjo and entitled ‘Waking Dream’, mixed the work of bold-faced names from the collection (Rachel Whiteread, Glenn Ligon, Wangechi Mutu, Isa Genzken) with local artists (Ana Fernandez, Ethel Shipton, Chuck Ramirez, Cruz Ortiz) as well as some artworks of Linda Pace’s own making. Fittingly, the show was by turns sombre and uplifting. A Cornelia Parker installation, Heart of Darkness (2004), made of charred branches and pine cones harvested in the aftermath of a wildfire in Florida, is suspended in the air as if in mid-explosion. An interactive work by Marina Abramović, Chair For Man and His Spirit (1993), which consists of two iron chairs, the first with a standard height, where viewers are invited to sit; the second soars up towards the ceiling of the main gallery, a nod to our strivings for spiritual elevation.

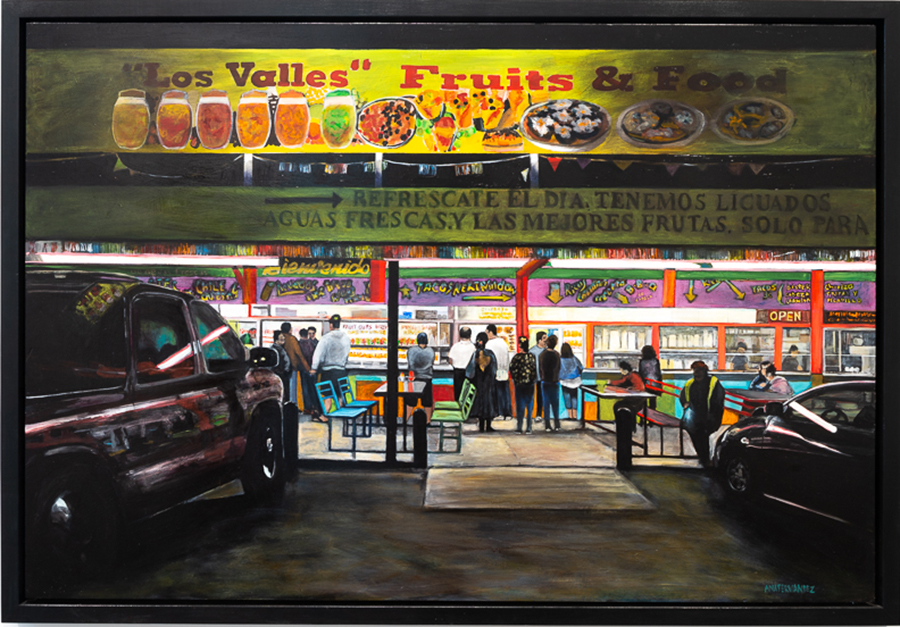

Menjivar, courtesy: Ruby City and Linda Pace Foundation

In addition to the curated exhibition, a large cerulean viewing room was given over to a three-channel Isaac Julien film work, Playtime (2014), the first of a number of Julien’s works that are slated to grace the space. The work features appearances by the actor James Franco, who plays a slick art dealer giving a ‘greed is good’ soliloquy for the art-boom era, the auctioneer Simon de Pury, who essentially plays himself, and a collection of late-capitalist archetypes (a jazz-playing, predatory hedge fund manager who purrs about conjuring capital out of thin air; a morose homeowner who laments losing his shirt to an Icelandic bank after the 2008 crash; and a lonely Filipina cleaner stranded in Dubai, longing to provide a better life for her distant family even as she bridles against the stifling foreignness of the futuristic desert city). When it was made, it was a film that I’m sure felt like a darkly painted picture of the topsy-turvy post-crash world in which the notion of ‘value’ was suddenly revealed to be nothing more than a sleight of hand. A mere five years later, and the film felt almost quaint in the face of our current dystopian dogpile. That made me shiver even more than the prairie winds.

‘Walking Dream’ continues at Ruby City, San Antonio, USA, through 2022.