Performing Ian White: A Choice in the Matter or The Room We're In

Watching Sharon Hayes and Evan Ifekoya pay homage to the late artist at Camden Arts Centre and remembering his ‘structured anarchy’

Watching Sharon Hayes and Evan Ifekoya pay homage to the late artist at Camden Arts Centre and remembering his ‘structured anarchy’

The Room We're In

Emily Roysdon is an artist and writer living in Stockholm, Sweden.

I just had to go onto my balcony and talk to myself out loud. The last time I wrote about Ian’s work was for his obituary and each false start here has been about Ian, or me or me and Ian. It’s always an exercise to divorce the artist from the work they themselves performed, especially if it’s your dear friend dead whose body wrote and made the work. But when I went to see the performances at Camden Arts Centre on 2 May it was two other artists who were performing the scripts of Ian White.

I arrived knowing this was a question about re-performance, with an emphasis on the scripts and scores and subsequently the choices of the artists invited to work with the material. I arrived as a friend, as a knowing and initiated spectator. I hadn’t yet seen the exhibition, but I knew I would be seeing images of Ian, just around the corner. The exhibition raised these questions of documentation, archive and re-performance. They were explicit and palpable as is demanded by a posthumous exhibition, by performance practice itself and by Ian’s practice in particular that took these conditions into the frame of the work.

I arrived and sat in the front row, as I tend to do, but in this case, it was also that I felt it would be too much to take the whole room into the frame had I sat in the rear. All the people, friends and friends of friends, whom I last saw at Ian’s memorial, now congregating to see Ian’s work live for the first time since his death. But as soon as the event began and Sharon Hayes took her place in the chair at the front of the room, I felt I should have given her a little more psychic space. Hayes, being well accustomed to performing in midtown Manhattan and public spaces all around, didn’t flinch at the proximity or the task of Ibiza.

Of the two performances that evening, Ibiza: A Reading for The Flicker (2008), performed by Hayes and Black Flags (2009), performed by Evan Ifekoya, I had previously seen Ian perform Ibiza on two occasions. These two works are in a trilogy, with a third, titled Democracy (2009–10), which I had also seen twice. (I commissioned Democracy for an exhibition, ‘Ecstatic Resistance’, at Grand Arts, Kansas City, in 2009.) Of the trilogy, Ian said: ‘Each performance initially assumes the format of a lecture from which it then radically deviates. In the process multiple vectors between authority and subjectivity are simultaneously figured via the recounting of sexual encounters, Tony Conrad’s seminal 1966 film, conceptual theatricality, PowerPoint, Tate Modern’s “interpretation” policy, the BBC World Service, Queen Elizabeth I, “dance”, gesture, still and moving images, love, hope, despair and friendship.’

Ian was an artist, writer, curator in whom I trusted to have wrought the aesthetic, formal, social and political resonance of each detail of what he was offering and how. Not to be always right, but rigorous, and asking for rigour in return. So, from my front and centre spot, when I noticed that Hayes’s chair faced the audience, as opposed to Ian’s chair having been askew to the desk, triangulating the audience, I read that detail as Hayes turning towards us. A direct occupation of Ian’s script offered, fully-frontal, to this audience five years after his death.

Hayes made another noticeable intervention, one that many in the audience could understand as a layering of her method and area of interest into this encounter with Ian’s work. She had a single headphone in her ear attached to a player. I understood that she was listening to a recording of Ian’s cadence as he had performed the work. In Hayes’s lingo, this is to ‘re-speak’, a political gesture that in this case resonates intimately as well. The pauses, breaths between the lines and rhythmic kicking of the beer bottle at their feet.

The choreographed bottle-kicking punctuated a titillating narrative of sexual misadventure that Ian/Hayes read, blocked by the sight and sound of The Flicker. The narrative gives way to a litany of no’s à la Grinder preferences/prejudices (‘no twinks, no total tops, no femmes, no bois, no straight acting, no blacks, fats, fems or asians, sorry does nothing for me…’), and then to Yvonne Rainer’s 1965 No Manifesto (‘no to spectacle/ no to virtuosity… / no to moving or being moved’). Ultimately, quoting Ian, it’s ‘not Ibiza, but the room we’re in’, and Hayes’s ability to occupy the role so soundly delivered this dedicated audience to Ibiza: A Reading for The Flicker: the work, not the fantasy or memory of another room.

The second performance was by Evan Ifekoya, who took on the Black Flags script. Ifekoya didn’t know Ian personally, they were asked as an adjacent practitioner, someone who works between moving image, performance and education in a similar manner that Ian had.

Black Flags is largely constructed out of a conversation Ian had with the Director of Interpretation at the Tate Modern in which he digs into the details of wall labels. Over the course of approximately 25 minutes, the performance layers droning sounds and a video of a man in track pants who is soon pinching his nipples and grinding the floor in a black hood as Ifekoya reads overhead projections of text, exchanging pronouns, deviating from the written to ‘she’, the character. The main body of the script is loaded with heavy lines like ‘they hang in the balance between the anxieties of interference and the demands of legibility. Between desire, need and duty’, and ‘authority can be measured and has physical properties.’ These sentences, written out from the wall labels interview, speak directly of institutional power and the body that confronts it, and the more I watched Ifekoya’s version of Black Flags, the more I thought this was the crux of their engagement. The spoken text is coupled with slides of a notebook, pages spread open with what I imagine to be Ifekoya’s hands, of abstract black drawings dividing up the space of the page, the lines of the notebook just visible beneath the black. These are Ian’s drawings and they are in a display case in the gallery adjacent to the performance room. Other slides appear, and I understand these to be Ifekoya’s intervention. They are pages, fingers spreading open, of an Octavia Butler book. This gesture, this addition, seems to me to be asking for further resonance of ‘black’, the feminist sci-fi power of Butler’s extensive brilliant oeuvre interjected into the black squares of a lined notebook drawn into abstraction, which is not a flag. I think of the epochal political difference between now and 2009 when this work was made. I think of Adrienne Edwards’s work on blackness in abstraction. And I think of how identity is teased and fragmented, obliterated and returned, throughout both of these performances.

Ifekoya didn’t sit in the face of the wind machine, upfront, as the script suggests, but moved between different seats in the audience, alternately being seen or heard. Hayes, who knew Ian, knew this work, sat up front, and listened in to Ian’s own voice as she re-enlivened it that evening. I appreciate that Ifekoya was brave and irreverent enough to search for their own route into the work, just as I am that Hayes could be so frontal. An unwavering principle of Ian’s was in making sure there was a choice, and I’m not saying too much if I claim to know that he would have wanted both artists to take liberties and make new space within the work, for this time, the room we’re in.

****

A Choice in the Matter

Steven Warwick is an artist, musician and writer from England, living and working in Berlin.

I first met Ian White in Berlin. I was doing a musical performance in the foyer space of Kino Arsenal, during the ‘Poor Man’s Expression’ show in 2011, in which White participated. During his performance-reading A Life, and Time: Alfred Leslie’s letter to Frank O´Hara + Roland Barthes on Racine (2011), an electric fan was turned on, blowing his lecture notes everywhere as he spoke from a Britney Spears head mic. It was absurd yet captivating and I was instantly taken by his structured anarchy.

As I entered ‘Any Frame is a Thrown Voice’ – White’s posthumous retrospective at Camden Arts Centre (curated by Kirsty Bell and Mike Sperlinger) – I was curious to see how his practice, rooted in the live moment, would function as an exhibition. The works here consist of solo and collaborative performances made between 2002 and 2012, before his 2013 death. Slides, video and recordings of spoken words and gestures were initially used in his live works as a form of expanded cinema, and here they function as an activation of the archive. White was interested in removing any definitiveness to his pieces, preferring an approach of ‘repetition and failure’, constantly morphing to allow the body of work to yield multiple readings, to queer itself.

Upstairs at Camden Arts Centre, a large, red theatrical curtain – originally used in Marriage á la mode et cor Anglais (2007) – hangs, sculpturally, as a free-floating border. Placed beside this is 6 things we couldn’t do, but can do now (2004/18). For this work, White and collaborator Jimmy Robert studied Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A (1966) and reproduced it utilizing flags (perhaps a reference to Rainer’s 1970 piece, Trio A With Flags). Here it is placed next to censored diaries with black ink blocks from Black Flags (2009), hung grid-like on the wall. All are objects that define and restrict movement, which resonates today politically.

Democracy (2009–10) is a live performance ‘about not having a choice, obviously’ using radio and a PowerPoint presentation. It is installed with four monitors showing different iterations of the piece, with slides projected on the wall and the BBC World Service played then, as now, live. It’s interesting to think about what would have been on the news broadcast when it was first shown, as I listen to reports of the British government’s latest iteration of Brexit proposals. White shows images of Elizabeth I and the 16th century garden at Kenilworth built by Robert Dudley with labyrinthine paths towards a phallic fountain, in an attempt to seduce her. He posits the garden (which had recently re-opened in 2009) as an order of mystery, possibility and trap. For White, ‘the garden stands for a system of power... a spiteful fabric and we are still in it ...’ – which can just as easily collapse like Robert Morris’s Column did in 1961.

Morris is a pertinent point of reference for White, given the artist's fluidity between performance, sculpture and writing, and also the 1974 photo of Morris in sadomasochistic fetish gear, shot by Rosalind Krauss. During the piece (performed in various iterations between 2009–10) White stands mainly on one leg, gradually defrocks himself, with one denim jean leg dragging the trousers outside towards the exit, whilst image and sound continue, the audience awkwardly wondering if the performance has yet ended or not.

Trauerspiel (2012) and The Neon Gainsborough (2002) – described by White as ‘Gainsborough's paintings as a slideshow read as psychotic as read by a gay hysteric’ – also provide an expanded take on a cinematic moment to facilitate an alternate reading of a situation. They evoke the theatricality and anti-taxonomical sensibility of Jack Smith, an artist who would constantly re-edit their work, or even the anarchical public interventions of Leigh Bowery. White’s work was often bursting at the seams with art historical references: an anarchic pedagogy which made sense in the context of White’s previous teaching and curating posts at Lux film archive, and the Horse Hospital London.

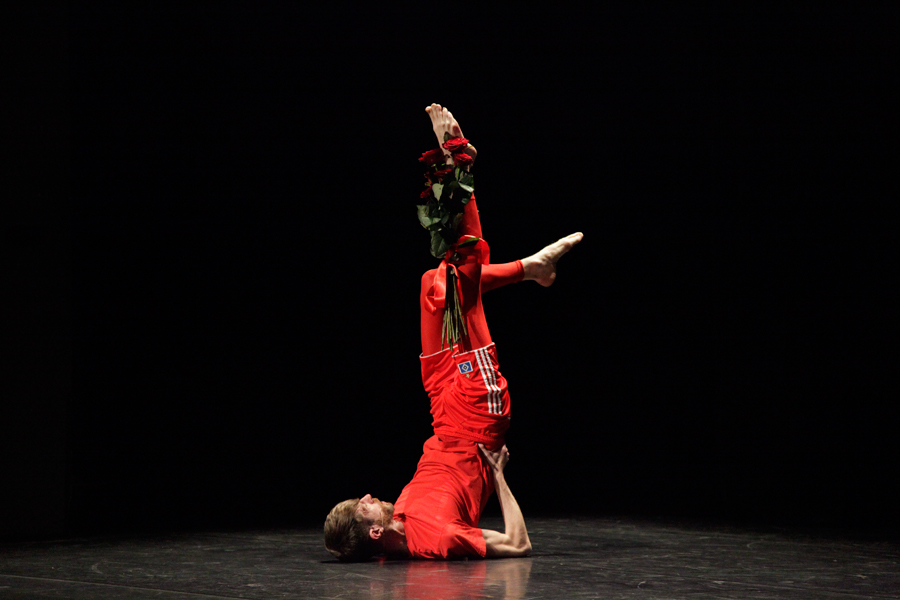

The Neon Gainsborough is one work which can easily function on its own as an installation, with timed lamps that beam onto blown-up pages from Transsexual-Transvestite News substituting the human turning them on, a slide projector of paintings and a VHS counter reading (‘This “fashionable pose” was copied from Watteau’, etc.), in accentuated Chaucerian English. Trauerspiel, one of White’s last works, was part of a commission from Kino Arsenal’s Living Archive, in which the artist selected five 16mm films from the archive and used the event to interrupt the film screening event with actions such as a naked man knitting, text scripts and a choreography. White’s oeuvre was and is one of constant change and possibility. The exhibition does not attempt to reify the pieces. It certainly does not feel stuffy but remains true to White’s intentions to re-read and refashion itself.

Once in 2011, I was out and about in Berlin after an opening, catching up with a friend and asked how their recent show in Vienna had gone. Ian butted in very loudly in his East London accent: ‘IT MEANS NOOOOTHIIING TO MEEEEE’ and started to snigger before pronouncing a bend of the wrist. My friend was very annoyed, and I couldn’t help but burst into laughter. It is this anarchic sensibility which thankfully manages to live on in the show, activating a gesture to unfold in the moment.

Main image: Ian White, Trauerspiel, 2012, performance documentation, Hebbel-am-Ufer, Berlin, 2012. Courtesy: the estate of Ian White; photograph: Nina Hoffmann