Photo Finish

Social division and artistic engagement in the work of Mohamed Bourouissa

Social division and artistic engagement in the work of Mohamed Bourouissa

In the short opening sequence of Mohamed Bourouissa’s Horse Day (2014), two riders on magnificent, shiny-coated horses prepare to race each other down a narrow stretch of park lawn. Spectators chat, joke and exchange cash bets; some of them hold their smartphones aloft to capture the animals bolting toward the makeshift finish line. In the next scene, cars carefully swerve around a lone rider clip-clopping along a charmless city street in Philadelphia. Nicknamed ‘The City of Brotherly Love’, this is where French-Algerian artist Bourouissa spent time getting to know the community around the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club, an inner-city stable that has been active for decades in this reputedly rough northern neighbourhood. Despite a longstanding equestrian presence in the city, the unusual sight of a posse of black urban cowboys, riding horses and ponies rescued from slaughter, has brought Fletcher Street considerable media attention. But the limelight hasn’t always shone favourably on the non-profit. In 2008, clashes with animal-protection agencies led the city government (many say wrongly) to demolish the buildings that served as stables and a clubhouse on a patch of land called Fletcher Field. Despite this, the initiative survived thanks to the dedication of the horse enthusiasts.

Some six years later, Bourouissa worked with the club to re-appropriate the land in order to stage a ‘horse tuning’ event – the subject of Horse Day and accompanying works in his recent exhibition at Munich’s Haus der Kunst. For the ‘horse tuning’, riders teamed up with local artists to ‘customize’ their equine vehicles, lavishly outfitting them for a festive riding competition that serves as the climax to Horse Day. Bourouissa’s approach to issues of race, social class and the repressed history of the African-American cowboy is not straightforwardly documentary, nor does it progress according to a fictional narrative arc. It relies heavily on footage of the everyday lives of the men who care for the horses, but also includes seamlessly integrated snippets of staged sequences and dialogues, mostly about the upcoming contest. In Horse Day, uncanny moments appear believable: an animal gets measured for its rainbow cloak of stitched-together compact discs; a crew of horsemen takes to the streets during a chaotic evening rife with the blaring noise of police sirens; a rider stops his beast beneath a train overpass to respond to a mobile-phone call.

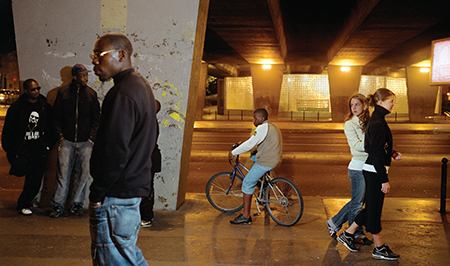

While Horse Day remains faithful to a cast of mainly marginal characters, Bourouissa’s work as a whole is deeply informed by the history and theory of photography. He established his fluency with a range of photographic modes in his series ‘Péripherique’ (Ring Road, 2007–08) and ‘Temps Mort’ (Dead Time, 2008–09). The former is a set of highly composed photographic tableaux inspired by the work of history painters and likened by some critics to photographs by Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Jeff Wall, while ‘Temps Mort’ is conceptually and formally driven by the technical capacities and small-screen contents of mobile-phone messages, photographs and videos Bourouissa exchanged (for telephone credit) with two acquaintances in prison. The title ‘Péripherique’ refers both to the ring road that delineates Paris proper from the banlieues – the suburbs – where Bourouissa grew up and the peripheral status of the populations living there. The zone made international headlines in 2005 when a clash with police left two teenagers dead and ignited fiercely destructive riots that spread across the country, leading the then-President, Jacques Chirac, to declare a state of emergency.

The quotidian drama of suburban life is palpable in Le cercle imaginaire (The Imaginary Circle, 2007–08) from ‘Périphérique’, which depicts a figure shrouded in a skeleton-printed hoodie standing almost resignedly in a ring of fire burning on a concrete floor. Shadowy characters emerge from the dark, graffitied corners, but no clues are given as to the nature of the ritual that is unfolding. Pathos seeps out of Le reflet (The Reflection, 2007–08), an image of an indistinct, hunched-over person sitting amidst a grey housing estate, facing a pile of abandoned televisions and computer screens that have been stacked on a circular section of pavement like a ready-made public sculpture. It would be hard to claim that these images seek to contest public perceptions of the tensions among French immigrant communities, but they don’t look to promote them either. Much has been written about the emotional spark that emerges from a photograph’s likeness to a given subject. But does the fact of the photograph’s staging somehow undermine that ‘likeness’? Here, Bourouissa renders the spark by drawing our attention to details of gesture and posture – an outstretched hand or quietly clenched fist, sloped shoulders, a stiffly defiant position of the head.

‘Péripherique’ required the complicity of Bourouissa’s models, while the photographer positioned himself simultaneously as director and implicated bystander. These are crisply composed and thoughtfully cropped images, with their dramatis personae caught, stop-action, in various scenes where trouble lurks. With ‘Temps Mort’, the grainy images of everyday items and occurrences that shuttled back and forth between Bourouissa and the prisoners via their phones are also the product of conversation and exchange, but here the boundaries between artist and subject are radically delineated by the prison block on one side and the domestic space of the artist’s apartment on the other. Their enlargement, editing, framing and display in the third space of the gallery simultaneously, and somewhat ambiguously, breaches and reinforces the distance between two incommensurable social and cultural milieus. It also raises questions about the works’ and, by association, the subjects’ cultural and commercial values.

Bourouissa tackled the disparate economies of the financial and commercial ‘products’ circulating in the art and culture markets in his 2013 exhibition ‘All-In’, at his Paris gallery, kamel mennour, and frac Franche-Comté. The exhibition title refers to a commission from La Monnaie de Paris (the Paris Mint), where coins are engraved and struck. Mimicking the bling-filled aesthetic associated with rap or hip-hop music videos, Bourouissa’s film, All-In (2012), follows the slow-paced minting of a coin bearing the portrait of the French rapper Booba to the soundtrack of his 2009 song ‘Foetus’. The Booba coin was sold during the all-night Nuit Blanche (White Night) festival for two euros. In his Paris exhibition, Bourouissa juxtaposed the video with photographs of the minting factory (Stock 1, 2013), a woman counting small change (Agnes, 2013) and a short video of his art dealer’s hand spinning a two-euro coin (Kamel, 2013), as well as framed versions of the Booba coin, produced especially to increase their market worth.

L’Utopie d’August Sander (August Sander’s Utopia, 2011–13) represents the other side of the coin, so to speak. When a cancelled residency project in Marseilles coincided with news in the region of mass lay-offs, Bourouissa decided to try to update Sander’s series of portraits, ‘People of the 20th Century’ (1910–40), which comprises hundreds of photographs of Germans from all walks of life. Bourouissa set up a mobile studio, complete with scanner and 3d printer, outside a local job centre, and asked volunteers to pose for resin portrait statuettes, or statues anonymes – a play on words in French between anonymous statue and anonymous status – which he then tried to sell at street markets for a few euros. This project is as much a commentary on the worlds of work, and the social stigma and financial pressures that accompany unemployment, as it is on the democratization of the mimetic machinery of 3D printing, which may soon become as accessible as the supermarket instant photo-developer. If Bourouissa’s stated intent was to create alternative, miniature monuments to potential heroes, the initiative was not welcomed by everyone. This led the artist to publish Les refus (The Refusals, 2012), a compilation of statements from some of those who declined to participate.

Questions of social and cultural status, and economic inclusion and exclusion, loom large in Bourouissa’s work, in part because of his focus on cultural values and clichés but also because of the contexts within which he and his work circulate. The artist’s pictorial engagement with socially or economically disadvantaged groups and the stereotypes we attach to them is consistent with a documentary ethos. But the technological and socio-cultural landscape of photography has shifted with the omnipresence of smartphone cameras and the worldwide explosion of social media. Bourouissa negotiates the profound influences of photography and film both as aesthetic representations and as methods of personal and mass communication.

Mohamed Bourouissa is based in Paris, France. In 2014, his solo exhibitions included a presentation of Horse Day as part of the Capsule programme at Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany, and 'Some Copyright Options' at AGO, Toronto, Canada. In 2015, Bourouissa's work will feature in the Biennale de Lyon, France, and the Havana Biennial, Cuba.