Portfolio: Dora Budor

From prop frogs to torture machines, the New York-based artist writes about the images she finds the most arresting

From prop frogs to torture machines, the New York-based artist writes about the images she finds the most arresting

Michelangelo Antonioni, L’Eclisse, 1962

Objects supplant actors in Michelangelo’s Antonioni L'eclisse (1962). The film compulsively returns to the scene pictured above: a collection of metal tubing and construction materials, all caught up ‘in progress of being.’ I have always been fascinated by the way that, throughout the film, various filmic techniques lead this amassing of inanimate matter to become an active participant. In close-up, for instance, the debris evokes a cubist composition, but when shot from a low angle it becomes a stand-in for the modern city. By emptying out the typical actor-driven narrative, the film makes room for actants to emerge. This is a universe where ‘thingness’ becomes a new structure for the world; a new vehicle for affect. This got me thinking about Siegfried Kracauer’s claim that ‘the cinema is not exclusively human.’ It was part of his larger thesis about the of the cinematic to render the actor as no more than a detail or a fragment in the matter of the world. This is something that has shaped my own obsession with objects in the cinematic sphere: their uncanny ability to materialize time and envision an agency that exists beyond the human.

David Jacob, Simulated Dwelling for a Family of Five, 1970

David Jacob’s biomorphic model for a single-family home was one of the most captivating pieces in the exhibition ‘Endless House’ at MoMA, New York, mounted on the 50th anniversary of Frederick Kiesler’s death. First raised in the late 1930s, Kiesler’s utopian proposition of ‘Correalism’ laid the conceptual groundwork for a host of breakthrough architects including Coop Himmelb(l)au and Asymptote. Kiesler envisioned the home as a living organism, not simply an arrangement of inanimate material. A dwelling could be as flexible and permeable as the skin on the human body – rather than make floor plans, he sought to map out the nervous system of the house. Jacob’s model is an elegant articulation of these tenets, the distinctions between its floors, walls and ceilings erased in order to create a free-flowing organic space, reminiscent of a mollusk or the shell of a snail.

From my boxy Chinatown apartment, I can’t help but wonder what a bright morning must feel like in this house. I hope that the destabilized space would make me experience my physicality in a completely different way.

Bernard Tschumi, ‘The Manhattan Transcripts’, 1976–81

Recently I was lucky enough to meet Bernard Tschumi, who I have been obsessing over since I first saw his ‘Advertisements for Architecture’. When I researched his work further, I was equally struck by ‘The Manhattan Transcripts’, parts of which were first shown at Artists Space in New York in 1978. At that time, Tschumi told me, Cindy Sherman was working as a receptionist, and in the other room there was an installation involving live goats that provided a melodic soundscape for his drawings and manifestos.

‘The Manhattan Transcripts’ explore the relationship between ‘the event’ and architectural space, assessing how they simultaneously confront and affect each other. These timely sequences of colliding vectors and masses have four episodes, taking different sites in New York as their starting situations. ‘The Park’ uncovers a murder in Central Park, for example, while ‘The Tower’ (or ‘The Fall’) depicts a fall from a Manhattan skyscraper. The Transcripts propose a structural reality constructed from actualities: bodies falling, running, desiring, and failing. What emerges is an architecture as true confrontation, taking form at the convergence of the real project, witnessed event and imaginary reconstruction.

Holy Motors, 2012, directed by Leos Carax

At the beginning of Holy Motors, we watch Monsieur Oscar (Denis Lavant) leave home for the day and climb into the back of a white stretch limousine. As the film progresses, we discover that Oscar works from the back of this limousine – it is his mode of transportation, his office, his dressing room, his restaurant – and that he is assigned a series of appointments at which he embodies various characters. We don’t get to know who he performs for, or what is the purpose of his interventions. The roles vary from an old beggar woman to a motion-capture actor who goes from toting a weapon to having simulated sex on a green-screen soundstage. Oscar also appears as Merde (a character reprised from Carax’s eponymous short film, which was made as part of the 2008 omnibus Tokyo!), a sewer-dwelling, gibberish-speaking sub-human. Most of the film’s plot concerns Oscar rushing back into his limo to hurriedly change and keep to schedule, applying makeup and masks, gluing fake fingernails, putting on different outfits.

The film becomes a study of an actor and perhaps also a dramatization of the evolution of cinema as it becomes digital and more fluid than ever. But at the same time, it is about the inchoate memory of film, with ghosts of previous performances, or seemingly semi-real events, haunting the screen throughout. For me, Holy Motors is the perfect film-essay, one that foregrounds its own production methods and Hollywood labor while also pondering our very own desire for filmic narrative.

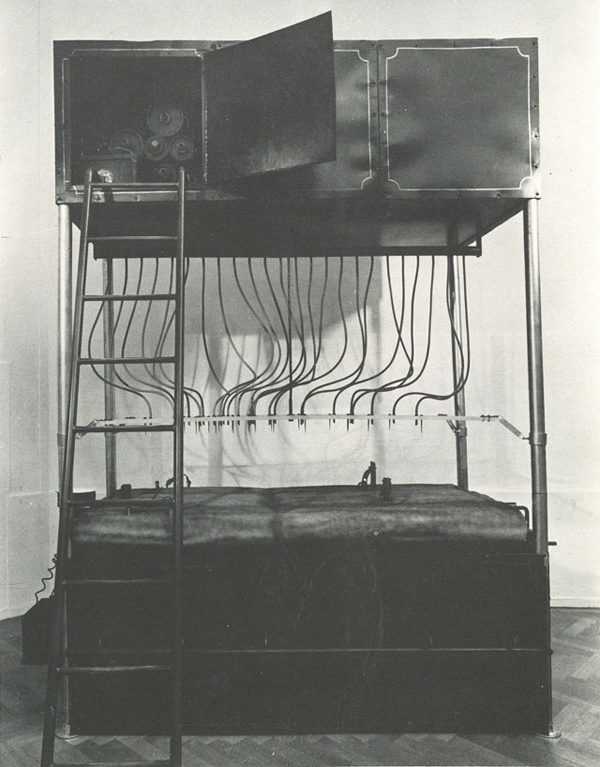

The Harrow

A friend recently referred me to this photo, which I found in the catalogue for the original show (Harald Szeeman’s 1975 exhibition ‘The Bachelor Machines’), where it was shown as a prop modelled after a machine from a Kafka short story. In the original text, it is vividly described as a torture device called ‘Harrow.’ In the context of the exhibition, the object was not attributed as a work of art, but rather presented as model to visualize an idea – a vessel turning fiction into a thing. My own practice extends from these types of objects which bridge the fictive and the actual; objects that are made to appear or perform a function on screen, but have no life outside of diegetic space. Extracted from their intended use, these objects appear incomplete and lacking in reality, but in doing so, they also question their own objecthood and open up unexpected conduits between memory, experience and time.

Prop frogs

I recently acquired all of the prop frogs made for the amphibian rain scene in Magnolia. They will be used in an upcoming installation, which deconstructs the scene into its elementary particles, and recreates it in relationship to the physical movement of bodies in the space. The supernatural scene of amphibian rain was introduced into the otherwise realist script somewhat unexpectedly, in something akin to a deus ex machina moment. Paul Thomas Anderson wrote it after reading Charles Fort’s Book of the Damned (1919), the first text written on theme of ‘damned’ data – the anomalous phenomena that has been excluded (or ‘damned’) by modern science. For the scene, Steve Johnson’s special effect studio produced thousands of prop frogs, which were broken down into three grades of realism: large quantities of lower quality deep-background frogs, a smaller number of mid-range frogs, and a very few ‘hero’ frogs that were paid much more attention, and were used specifically for close ups. Seeing them en masse, the bodies have a very uncanny appeal, appearing as lifelike and animate, but making you aware that they are not what they represent.

Study of the workshop working on a plaster mockup of the Statue of Liberty by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in the ateliers of Gaget, Garthier & Cie, c.1878.

When I last visited Paris, I spent two days in the collection of Musée des Arts et Métiers, a museum founded in 1794 in order to preserve scientific instruments and inventions, and map major historical innovations. One of the objects that caught my attention was this study of the making of the Statue of Liberty, the first monument in history to be built from a ‘kit’. It reminded me of the process used in my last show, ‘Ephemerol’, where I worked with a film studio to reconstruct a large destroyed sculpture from David Cronenberg’s 1981 film Scanners – I made a mold from it, destroyed the replica of the original, and then exhibited the mechanism that I first used to reproduce it.

Main image: Study of the workshop working on a plaster mockup of the Statue of Liberty by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in the ateliers of Gaget, Garthier & Cie c.1878. In the collection of Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris