Postcard from Guatemala

In lieu of institutional support, artists are working together to achieve a remarkable self-sufficiency

In lieu of institutional support, artists are working together to achieve a remarkable self-sufficiency

The smallest contemporary art museum in the world is shaped like an egg. Nestled between two busy boulevards in Zona 10 of Guatemala City, Nuevo Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (NuMu) – housed in a disused egg kiosk – measures just 2 by 2.5 metres, and can host around four visitors at a time. Framed by squat concrete buildings painted with the lurid palette of corporate billboards (¡McPollo! ¡McAgua!), NuMu’s idiosyncratic appearance and location are emblematic of its mission: to challenge concepts of what – and where – a museum can be. Founded in 2012 by artists Jessica Kairé and Stefan Benchoam, the museum responds to Guatemala’s scarce public funding and paucity of private support. However, its inventiveness is also emblematic of the creative freedom local artists enjoy, free from institutional or market pressures. Above all, the museum serves as an oasis in a city characterized by neglect and violence. NuMu is part of a process to revive the city’s public spaces, marred by decades of bloody civil war that raged from 1960 to 1996.

In NuMu’s miniscule right wing hangs an olio of classical paintings, prints, drawings, ceramic pieces and textiles, part of ‘Fantasía’ (Fantasy), the first solo museum retrospective of work by Austrian-born, Guatemalan-based Elisabeth Wild. The left wing is given to Wild’s intimate collages, also on view at documenta14 in both Kassel, Germany and Athens, Greece. Technicolor geometric patterns form surreal scenes, strikingly at odds with Guatemala City’s urban landscape. NuMu’s programme brings Guatemalan artists in conversation with international stars, like Pia Camil and Amalia Pica; in August, a replica of the egg will travel 3,000 miles to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), to participate in ‘Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles/Latin America’ (PST LA/LA).

In Zona 1, through the heavy doors of a wood mill, lies Proyectos Ultravioleta, a hybrid Kunsthalle and commercial gallery. Founded in 2009 as a project space, it now represents some of the country’s most prominent artists, from Regina José Galindo to Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa. Participating in a few select art fairs, it generates international exposure and much-needed revenue. Walking through neat rows of cacti, I entered the gallery’s exhibition of large-scale, abstract paintings by Fernando Iturbide, ‘Emociones modulados’ (Modulated emotions, 1979). While Iturbide’s name is recognized in Guatemala (after the artist passed away from HIV-related complications in 1993, his nephews founded Fundación Fernando Iturbide, an organization raising awareness of the virus), his art is relatively unknown. In Iturbide’s paintings, pastel-coloured darts dash across oceanic backdrops and form rhythmic patterns. In a letter written in 1980, the artist described his practice as a tool to transform his negative emotions into something more positive. Although he determined the works as deeply personal, he saw it as the artist’s duty to share such a discovery.

At Galería Extra, a gallery founded by artist Renato Osoy in early 2017, I caught the last few hours of ‘Kab’Awil’ (Two opposing yet complimentary forces), a solo show by the Mayan artist Manuel Chavajay. Chavajay’s work tackles the contemporary status of his people, the Tz'utujil, one of 23 Amerindian groups in Guatemala who make up around 40% of the population. A series of small-scale paintings in DayGlo acrylics, ‘Naquun (Objects)’, depict everyday items from his hometown, San Pedro La Laguna. In Chavajay’s still lifes, plastic baskets brim with red tomatoes, flowers spill from tin cans and bananas balance on rusting wheelbarrows. These illuminated objects hang suspended in black voids of space – the night is sacred in Tz'utujil culture. Located on volcanic Lake Atitlan, San Pedro La Laguna is a town divided. The shore is packed with tourist bars and vegan cafes, yet a short walk up the hill leads to the ancestral homes of the Tz'utujil community. Chavajay’s still-lifes document a moment of transition, as the creeping forces of globalization encroach on San Pedro, and the country’s Mayan peoples attempt to co-exist with new urban development. Their starkly contrasting palette echoes this conflict, drawing hues from the traditional dyes used in Tz'utujil textiles but also the logos emblazoned on the facades of Guatemala’s vernacular architecture.

Chavajay’s film Oq Ximtali (They have tied us, 2016) documents a performance on the waters of Lake Atitlan from above. A group of 17 fishing boats converge in a circle, their sterns bound with rope to form a star. The fisherman row throughout the performance, the clunk of oars punctuating the lake’s lapping tides. Chavajay had directed the fisherman to work together to break free; later, at his studio, he told me that he sees their failure to do so as a metaphor for his people’s submission to economic and political corruption. Chavajay is currently at work on a series of large oil paintings depicting empty boats bobbing on the waters of the lake, representing the many desaparecidos who vanished during the Guatemalan civil war and Mayan genocide, including members of the artist’s own family.

Guatemala is still recovering from the traumas of the past half-century. In lieu of institutional support, artists are working together to achieve self-sufficiency, healing the country’s wounds through dialogue and creative expression.

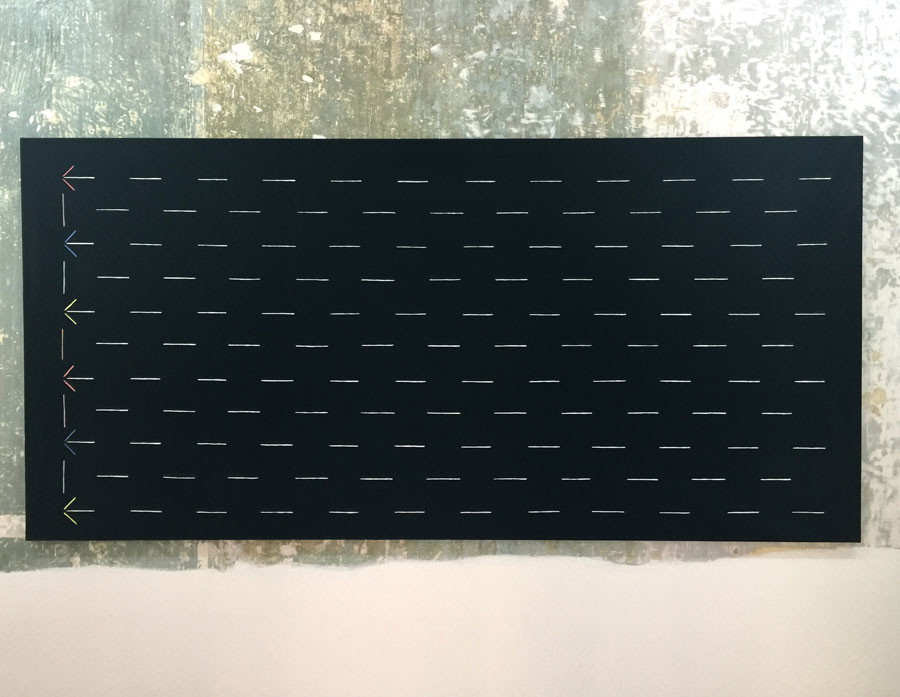

Main image: Joaquin Orellana, Paisaje Sonoro (detail), 2016, installation view, NuMu, Guatemala City