In Profile: New North and South

A new network links up arts organizations from the north of England and South Asia, reimagining a more equitable cultural relationship

A new network links up arts organizations from the north of England and South Asia, reimagining a more equitable cultural relationship

Arts organizations from the north of England and South Asia have come together to create the New North and South network. The collaboration will foster a three-year series of exhibitions navigating a shared heritage, as well as deeply contested histories of empire and trade.

In 2017, the New North and South programme focuses on Manchester. This month, Raqib Shaw will bring a solo show to the Whitworth, in a personal exploration of Kashmiri aesthetics that also draws on the gallery’s own textile collection. Other projects scheduled for this September include a performance piece by Mumbai-based Kashmiri artist Nikhil Chopra that takes inspiration from historic objects in Manchester’s Museum of Science and Industry, as well as the first major UK exhibition from New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective, who will dive into the city’s history of radical politics.

We spoke to Nick Merriman, director of Manchester Museum and interim director of the Whitworth, as well as lead spokesperson for the New North and South network, about the complex political and cultural relationships – past, present and future – that the partnership is engaging with.

En Liang Khong What was the initial impetus for the 'New North and South' project?

Nick Merriman The starting point was a realization about audiences in Manchester. In the city, 13% of the population is of South Asian heritage but we realized from audience research that only about 3 or 4% of our audiences were from that background. One obvious reason is that we don’t present much South Asian historic or contemporary art. We were also aware that this year is the 70th anniversary of the partition of British India.

Our partnership stemmed from Manchester: Manchester Museum, the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery. Including the Liverpool Biennial and The Tetley in Leeds gave us a good geographical spectrum. Liverpool and Manchester have traditionally been cities that see each other as rivals and we wanted to do something together in the spirit of cooperation. For the South Asian institutions, we looked to biennials that seemed to be leading contemporary practice. Colleagues such as Maria Balshaw went to the Dhaka Art Summit and saw the dynamism there. We added the Karachi and Lahore Biennales – the latter with Rashid Rana as artistic director who we knew from other collaborations. Colombo is really the only art biennial in Sri Lanka, so we wanted to engage with it. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale – although there are a number of biennials and art fairs in India – seemed to be one of the most exciting.

So we are co-commissioning work to be shown in the north of England and in South Asia. The programme is called the ‘New North and South’ which is about reimagining more equitable relations between the north of England and South Asia, given the historic ties between the two parts of the world – and a long legacy of imperialism. But while our artists share a South Asian heritage, we are also giving them solo shows – it's not a group show of South Asian artists. We also realized that one of the barriers to showing South Asian art in the north of England was that our curators didn't know much about the scene there. So the project has provided resources to allow our staff to spend time in different countries in the region. By the same token, we've been providing assistance and training in installation and art handling, to meet the needs of the South Asian biennials we are collaborating with.

ELK How did particular histories of marginalization and UK-South Asian relations inform your mission?

NM We very deliberately called our project the New North and South because it was about the North as a cultural counterpoint to London. We wanted to foreground the role that culture has played in regenerating cities of the north, particularly in Manchester where long-term political stability and support of culture has explicitly been seen as part of the city's overall socio-economic regeneration.

In South Asia, at least in part, we were thinking about choosing places that were not major cities – so Kochi is obviously not Calcutta, Mumbai or Delhi, but it's also a big historic port which was originally one of the gateways to the Western world. That was an obvious link: we were building on our understanding of history and trade between the north of England and South Asia, particularly around cotton and textile production. Some of the artists we've chosen are very interested in that interaction.

ELK Let’s talk about the projects beginning this year. How will Raqib Shaw's exhibition at the Whitworth begin to explore the suggested themes of New North and South?

NM Diana Campbell-Betancourt, the artistic director of the Dhaka Art Summit, approached us offering a partnership with Raqib Shaw, based on his new works exploring his memories of Kashmir. Kashmir is still a disputed territory between India and Pakistan, and so this is a particularly interesting moment to look at this. If there's any theme at all, it's about division, identity, rupture, migration and transition. Shaw very much wanted to address these in his works, and so we thought about showing it in the Whitworth: he's made a new wallpaper, and chosen works from the Whitworth collection. It will tour to Dhaka next February, as an imagined room installation drawing on the artist’s memories of Kashmir.

ELK Nikhil Chopra is also another key artist for New North and South, and he’s worked before on historically informed projects in Manchester.

NM In 2013, Nikhil Chopra made a commission for the Whitworth called Coal on Cotton. Performance art is a particularly interesting and emerging strand of South Asian art. So we invited Chopra to the Museum of Science and Industry which includes this great locomotive in the museum's Power Hall. It had been made in Manchester, bought by the North West Indian Railways, before being transferred to Pakistan Railways after Partition in 1947. In the 1980s it came back to Manchester as a piece of Cold War diplomacy.

Chopra was seized with the possibility of doing something with this engine. As well as the fact that the museum itself is the site of the world's first passenger railway station – the first passenger service in the world was from Manchester to Liverpool. We still don't know what he's going to do exactly, but we trust him.

ELK What other exhibitions complete the first phase of New North and South?

NM We've got a series of exhibitions that have opened already: a small photographic exhibition by Sooni Taraporevala who is an Indian filmmaker and photographer; a redisplay of the Whitworth's textile gallery called 'Beyond Borders' which has four contemporary artists from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and England putting their own works in and choosing pieces from the Whitworth's historic South Asian textile collection.

On 30 September we are opening a number of shows across Manchester. We will have the first solo show in the UK by Raqs Media Collective, which will encompass existing work like the 'Coronation Park' sculptures that were shown at the 2015 Venice Biennale, as well as new pieces. They have spent quite a lot of time in Manchester. They are interested in the city as the home of radical thought, the home of women's suffrage, the place where Friedrich Engels spent his adulthood and was visited by Karl Marx.

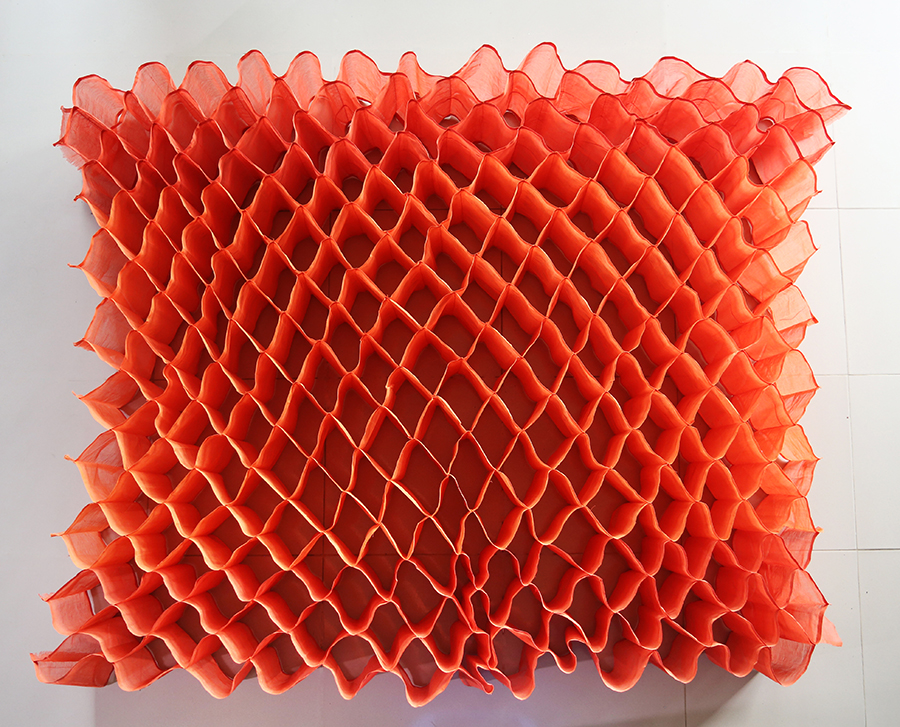

At the same time, Reena Saini Kallat will present work at Manchester Museum explicitly addressing the theme of partition. She has created sculptures out of barbed wire and rubberstamps, as well as bifurcated animals, where she will take the national animal of India and Pakistan and then splice them together. She has a personal family story – her family come from Lahore, which is now Pakistan, but because of their religion they all had to move to India for fear of their safety.

ELK After Manchester, the focus shifts to the South Asian biennials – the Dhaka Art Summit kicks off in February 2018 – where we will see artists previously shown in Manchester as well as new commissions. The co-commissioning between the various institutions of ‘New North and South’ is still work-in-progress, but what are the challenges and possibilities in working closely with the South Asian organizations?

NM Sometimes we can make assumptions about how a biennial will work in Liverpool, say. In Karachi, nearly the entire budget is given over to security. They have to pay for three layers of security before you can get into the building, which obviously gives a very different flavour to what they are achieving. Then they are spending money on generators as they don't have a regular electricity supply, to make sure the lighting and AV works.

The South Asian biennials are explicitly political. The Lahore Biennale, for instance, is trying to evolve an approach so that much of the exhibition takes place across the city, aiming at a politically engaged, spatially distributed art – mapping the city is a really important part of what they are doing. They are getting artists to map the city in different ways, right down to the underground tunnels and sewage systems. They are bringing international and national artists into a very politically charged context, but in a way that is nevertheless part of an international biennial scene.

The great hope had been that the South Asian biennials would work together. One of the issues we've come up against is that, because of the political histories between them, often they can't travel to each other's country. With the Kochi Biennale, most people from Pakistan could not attend, because they couldn’t get visas. We are inviting them all to Manchester for training and colloquiums because they can all travel to the UK; we are also running workshops in Dubai, where they can all travel, as a kind of neutral space.

ELK How have political events in the UK fed into discussions about the direction of your project? The project's themes encompass acknowledging histories of empire – and many critiques of the Brexit vote in the UK have cited imperial nostalgia or even imperial amnesia.

NM All of our collections in the Manchester institutions are essentially imperial. The collection of Manchester Museum is from all over the world. And with Manchester Art Gallery and the Whitworth, the money that generated the ability to acquire the textile collections or the paintings came from imperial trade and connections. We wanted to show our audiences that a lot of what we see today was fuelled by empire – I don't know about truth and reconciliation, but at least we can acknowledge that story.

Since Brexit, I think all of us feel there's even more of an imperative to work internationally both in Europe and beyond. The essence of what we do is international. Manchester is an international city too, and South Asia is an important part of our historic legacy and our future.

Nick Merriman is the director of the Manchester Museum, Interim Director of the Whitworth, and lead spokesperson for the New North and South network. Previously, Merriman worked at the Museum of London and University College London. He is Honorary Professor of Museum Studies at the University of Manchester.

Main image: Reena Kallat, Woven Chronicle, 2015, circuit boards, speakers, electrical wires and fittings, 10 min Single Channel Audio, installation view. Courtesy: Vancouver Art Gallery; Photograph: Rachel Topham