Rearviews & Mirrors

Architecture, idealism and anachronism in the work of Cui Jie

Architecture, idealism and anachronism in the work of Cui Jie

‘When the real is no longer what it used to be, nostalgia assumes its full meaning.’

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation (1981)

Representations of the future always look dated as soon as the future itself arrives. Part of China’s post-1980s generation, the artist Cui Jie makes paintings that continually confound our sense of time in their seeming nostalgia for the future. Set against a metallic sky and often floating above a similarly reflective gridded ground, Cui’s technically exquisite renderings of built forms not only capture a specific typology of urban China’s modernist artefacts; together with her more recent sculptures, they scrutinize the veracity of modernism as an ideology claiming the future. To the artist, who did a residency last year in Tel Aviv, the flawless International Style of the white city is appealing but not all that ‘interesting’. What compels her is precisely the opposite: the seemingly arbitrary, erratic and often jarring juxtaposition of an appropriated modernism against a context that is, in itself, rapidly shifting. Reconstructed amidst the chaos of China’s urban transition, the pristine, future-facing forms of Western modernism read as anachronisms.

In the two decades since the beginning of China’s accelerated economic liberalization in the late 1990s, GDP per capita has multiplied more than tenfold. This vast economic growth has propelled the country into the global arena, facilitated by the rapid urban transforma-tions wrought on its built environment. The cities of the once self-isolated and ascetic communist nation have, by wiping out large swaths of existing urban fabric, become bastions of gleaming towers and lustrous malls: spatial manifestations of a new capitalism.

To Western theorists, like the ever-polemical Rem Koolhaas, East Asia’s rapid urbanization has come to epitomize what he dubbed, in the mid-1990s, the ‘generic city’: the relentless spatial repercussions of a pervasive modernization accelerated by globalization. Repetitive to the point of being banal, the ‘generic city’ has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In movies such as Her (2013), a techno-futuristic Los Angeles is depicted against the backdrop of Lujiazui, Shanghai’s financial centre and an emblem of state capitalism. With mixed envy and awe, popular representations of emerging-world developments divulge more about the postindustrial West’s anxieties over an economically rising East Asia than they reveal the region’s specificities.

Cui, who grew up in Shanghai during the era of rising steel and glass, snubs these symbolic urban showpieces as Potemkin artifices that do not reflect the full story of contemporary China, nor the ruthlessness of its mod-ernization and marketization. She focuses, instead, on the more austere, less conspicuous, but ubiquitous mod-ernist slabs of the late 1980s and early ’90s. Fusing and flattening renderings of these unloved civic and residential buildings with depictions of selected transition-era public sculptures, whose socialist motifs are often propagandic displays of China’s technological aspirations, Cui lays bare the uncanny experience of the Chinese everyday.

In Worker Cultural Palace in Dongguan (2014), a sculpture composed of three interlocking circles bisects a rectangular building shown in perspective. The building, with a strip of ribbon windows on its long side and circular portholes on its shorter face, sits on top of pilotis. It epitomizes stylistic modernism: ribbon windows and pilotis are two of the five points of architecture that Le Corbusier preached as essential to International Style. More idiosyncratic are the additions of a semi-circular bulge in its rectilinear volume and a glass-clad circular tower. The latter is emphasized by its intersection with the swirling sculpture, which – resembling planetary orbits or atomic circuits – would remind a Chinese viewer of the symbol used to denote science on the covers of 1980s school notebooks. Analytical and perceptual, in sensibility Cui’s representations are more akin to Eadweard Muybridge’s 19th-century movement studies than to the undulating, futuristic architectures of Ma Yansong that they resemble at first glance. If anything, Cui’s fascination with China’s awkward re-encounter with modernism echoes the experiments of early-20th-century European artists, such as Robert Delaunay and Fernand Léger, who captured the rapidly industrializing built environment of their own era.

It was in 2009, following Cui’s move to Beijing from the compact commercial hubs of Jiangnan (the region south of Shanghai including Hangzhou, where she graduated from the esteemed China Academy of Art), that her interest in the structures of modernism developed. Having grown up during the heady economic transition of cosmopolitan Shanghai and studied in the intricate historic town of Hangzhou, the artist found the imperially scaled urban grids and coarse geographies of the northern capital vast and foreign. She spent more than two months detailing every plaza, park and footbridge in particular areas of Beijing, systematically documenting the built environment in order to comprehend her new habitat.

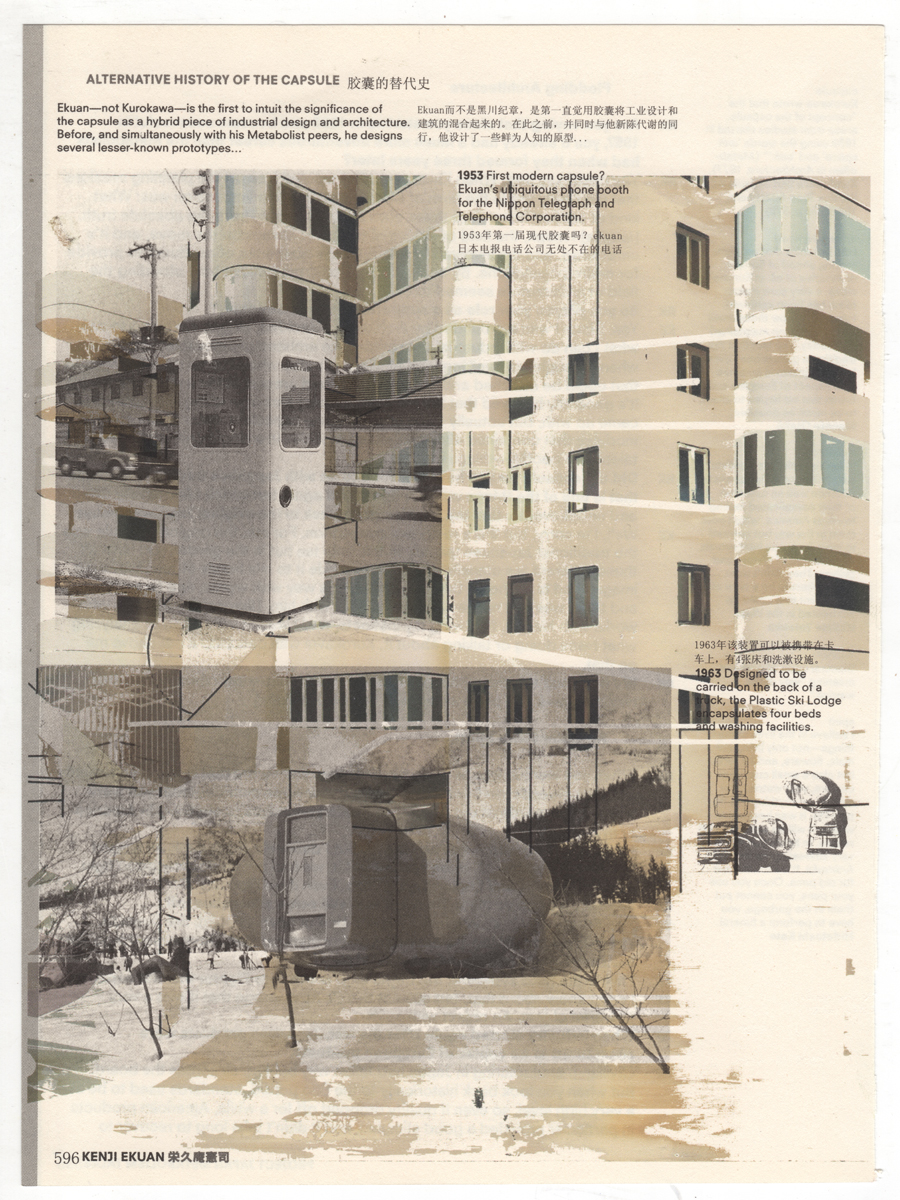

Cui discovered that the cylindrical and dome-shaped features of many Chinese buildings were appropriated from the visual language of the Japanese metabolists – a postwar architectural movement that adapted Western modernism to envision a utopia of technology and large-scale urbanization in the Asian context. Her 2014 series ‘Project Japan’ collages photographs from Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist’s eponymous 2011 book with images of metabolist-inspired constructions in contemporary China. The cinematically inspired fade-outs meld in overlapping layers, bringing together source buildings and their Chinese offspring, blurring past and present.

In much the same way, the artist’s 2017 ‘Architecture and Sculpture’ series fuses public sculptures erected during China’s optimistic era of scientific positivism in the 1980s with contemporaneous modernist transplant buildings. The sculptures – 3D-printed in white resin and around 50 centimetres tall – make physical what Cui imagines in her large-scale paintings. A result of the preparatory process for her monumental work Pigeon’s House (produced for Cass Sculpture Foundation in Sussex in 2016), the ghostly white structures offer a new mode of retaining memories of the ever-changing cityscape.

Cui’s clinical renderings of her everyday world do not so much diagnose as magnify the specificities of modernism appropriated. In doing so, the artist turns the fable of China’s ‘generic cities’ inside out. Koolhaas himself, while pioneering architectural research into the ‘wild East’, had demanded a new framework for comprehending ‘the maelstrom of modernization’ that is ‘least understood at the very moment of its apotheosis’1. Cui seems to be honing a method befitting the ever-evolving built environment. Her works may not have been conceived as an homage to the recently deceased artist Geng Jianyi, who preceded her by one generation and belonged to China’s postsocialist vanguard. But, on some level, they continue his spirit of interrogating the presumed inevitability of modernization.

In her recently opened exhibition at OCAT Shenzhen, Cui probes the origin of the modernist myth by taking on one of Le Corbusier’s unrealized designs. Cui was intrigued by the relationship between the Swiss French architect and the prominent mathematician Professor Rudolf Fueter, for whom Le Corbusier proposed a lakeside house that was never built because of the academic’s passing. The show reconstructs Le Corbusier’s proposal in OCAT’s vast warehouse space, creating an intimate, domestically scaled installation that guides the viewer through a careful choreography of Cui’s paintings, sculptures and sketches. A new work, Spiral Recliner (2017), confronts Le Corbusier’s attempt to rationalize the body through mathematical proportions by slicing through a spectral outline of his famous chaise longue with a vertical spiral sculpture, like those often found in front of Chinese primary schools. A female figure, painted from a different perspective and rendered similarly phantom-like by scraping away the top layer of paint, seems to lie atop the chaise. By using a moiré pattern – derived from wave mathematics – to produce the silvery shadows cast by the body-chair-sculpture, Cui undermines modernist standardizations of the body.

This recent introduction of figures brings the artist’s work full circle. From the dreamlike spaces of reconstructed memory to the flicker of the human body and its shadow in her latest work, Cui’s representations of urban China’s fleeing present upend assumptions about its future.

Cui Jie is based in Beijing, China. Her exhibition ‘The Enormous Space’ is on show at OCAT Shenzhen, China, until 8 April. In July, her work will be included in the inaugural edition of Front International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art, USA. Recent group exhibitions include ‘Past Skin’, MoMA PS1, New York, USA, ‘The New Normal: China, Art and 2017’, Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, and ‘A New Ballardian Vision’, Metro Pictures, New York (all 2017).

1 Rem Koolhaas, ‘City of Exacerbated Difference’, in Great Leap Forward / Harvard Design School Project on the City, ed. Chuihua Judy Chung et al., 2002, Taschen, Cologne, pp. 27–28

Main image: Workers Cultural Palace in Dongguan, 2014, (detail), oil on canvas, 1.5 x 2 m. Courtesy: the artist and mother’s tankstation, Dublin / London