The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Spain’s First Modern Art Museum

The challenges faced by the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern have involved a form of firefighting that many museums outside of capital cities seem in thrall to

The challenges faced by the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern have involved a form of firefighting that many museums outside of capital cities seem in thrall to

On the night of 19 March 2017, artist Fermín Jiménez Landa lit a match from the embers of a smouldering monument in a square within the Spanish city of Valencia. From that flame, he lit a candle, then a lantern, then a gas heater, keeping the fire alive through various technologies for 365 days and nights, until it sparked the incineration of his own monument: a wooden representation of an apartment block. Jiménez Landa’s action was part of Valencia’s fabled fallas festivities, which culminate each Saint Joseph’s night with a vast spectacle of burning across the city, as hundreds of elaborate sculptures – conventionally, groups of clownish figures – are sent up in smoke. Since the middle ages, the fallas have brought a satirical zest, and an irresistible primal symbolism, to Spain’s third-largest city. They’re a searing reminder of the transience of art.

After 30 years, the story of Valencia’s art museum, the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM), seems inescapably haunted by the allegorical possibilities of the fallas, in which hubris and exuberant expenditure are sacrificed and careful craft is reduced to ashes, only to rise again. IVAM’s first flush was as an energetic international pioneer, yet it was consumed by the provincial corruption that dogged the Mediterranean city until recently. In many ways, the challenges faced by IVAM have involved a form of firefighting that many museums outside of capital cities seem in thrall to: a volatile mix of patching-up and starting anew, regional populism and political critique, tourism and the local community.

Located on Spain’s southeast coast, and with a population of some 2 million, the port city of Valencia lies a few miles away from the Albufera, a vast freshwater lagoon, and evolved from the surrounding rich agricultural land. When, in 1989, IVAM opened the doors to its imposing, new, slab-like building on the edge of what was once the city’s medieval walled core, it was on fertile ground for other reasons – Valencia’s two universities and lively club scene meant that there was a young public eager for new cultural experiences. It was the first public museum in Spain dedicated to collecting and exhibiting 20th-century art. Predating the 1992 official opening of Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and Barcelona’s contemporary art museum, MACBA, in 1995 – and before the Guggenheim franchise landed in Bilbao in 1997 – IVAM represented the first attempt in Spain to disrupt the fusty ‘bellas artes’ (fine arts) museum model and kickstart a fresh and modern artistic identity that could match the energy of a still-young democracy.

A political project from its inception, IVAM was first propelled by the socialist government of Felipe González. Yet, as Valencian regional politics was steadily engulfed by the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) and systemic corruption, and with debts mounting from pharaonic infrastructure projects (such as Santiago Calatrava’s City of Arts and Sciences, a complex of photogenic buildings, plazas and parks designed to rejuvenate the area around the former river Turia), IVAM suffered the virtual immolation of its reputation at the hands of its director from 2004–14, the divisive, flame-haired PP loyalist Consuelo Císcar.

In 2016, Císcar, who had treated IVAM as her personal fiefdom, was charged with multiple counts of embezzlement and misuse of public money along with four senior staff members. Work of frequently dubious merit had been bought for vastly exaggerated prices and inflated contracts reeked of nepotism – more than €2 million disappeared into an in-house magazine, for example. Sixty photographs were purchased from Gao Ping, sometime art dealer and presumed head of a Chinese mafia dedicated to money laundering, who is now in prison. Public money was even spent promoting the art career of Císcar’s son. As IVAM lost not only its spark but its institutional integrity in overlapping self-serving interests, the Valencian art world continued to adapt and evolve. Galleries – including Luis Adelantado, espaivisor and Rosa Santos – took up the slack. In 2017, the art centre Bombas Gens arrived on the scene in a former 1930s hydraulic pump factory, based around the Per Amor a l’Art collection of Susana Lloret and José Luis Soler, whose company supplies the supermarket giant Mercadona.

IVAM’s affable current director, José Miguel G. Cortés, was appointed by open competition in 2015 during a seachange in regional politics that saw a swing to the left and multiple criminal indictments against PP figures, including Rita Barberá, Valencia’s tainted mayor from 1991 until shortly before her death in 2016. Cortés has brought a steady hand to the perilous task of navigating IVAM out of the doldrums and rekindling the museum’s credibility. Under its first two directors, Tomás Llorens and the late Carmen Alborch (who left in 1993 to become Spain’s charismatic minister of culture), IVAM’s first decade bore out a canny strategy for building a collection and programme from scratch that would have local relevance and international reach. Trying to emulate the dynastic story of modern art as told by New York’s Museum of Modern Art or Paris’s Centre Pompidou was inconceivable. Instead, the collection was forged from a bulk acquisition of the work of one artist – the Barcelona-born sculptor Julio González (1876–1942). The resulting complexities cut a swathe through the avant-gardes and politics of pre-World War II Europe, while reaching out to other ‘minor’ versions of modernism, from the Netherlands to Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union and back to Valencia. Concurrently, the hundreds of González sculptures that came into the collection – as well as paintings by another early nucleus, the impressionist Ignacio Pinazo – would be given as much importance as the acquisition of supposedly marginal media such as posters and magazines.

As the collection followed little-trod pathways, connections opened up between, for example, 1970s Valencian political pop art and the 1930s photomontages of the anti-fascist German artist John Heartfield. The first decade of IVAM also saw it vigorously pursue a series of eyecatching international collaborations, Spanish debut shows and an adventurous programme for the neighbouring Centre del Carme, a former 13th-century monastery. (The Centre is now a city-run space operating independently of IVAM and currently exuding its own air of renaissance.) Curator Vicente Todolí was a key part of the IVAM cadre from the beginning, working alongside Llorens, Alborch and, later, José Francisco Yvars. (Todolí now directs Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan.) At one time, in the 1990s, the young, stellar curatorial team included Nuria Enguita (now directing Bombas Gens) and Bartomeu Marí (who now heads Museo de Arte de Lima).

The opening-year programme at IVAM included the first survey exhibition of Richard Prince. Peter Fischli & David Weiss were featured the following year. A 1992 show of Gordon Matta-Clark later travelled to Marseille and London. Eva Hesse was introduced to the Spanish public at IVAM in 1993 (unfortunately, the only solo show given to a woman in five years) and Cildo Meireles in 1995. Agustín Pérez Rubio, one of the curators of next year’s 11th Berlin Biennale, was born in Valencia in 1972. ‘The IVAM of the 1990s was more than a reference for me. I grew up seeing and studying the exhibitions, attending the conferences and seminars, and studying in the library,’ Pérez Rubio recently told me. ‘I sincerely believe that if that model between the regional and the international, that magnificent collection and exhibition programme, had not existed, I would not be the curator and museum director that I am today.’ In an interview in 2014, Marí, then director of MACBA, said that his model for the institution was the IVAM of the 1990s.

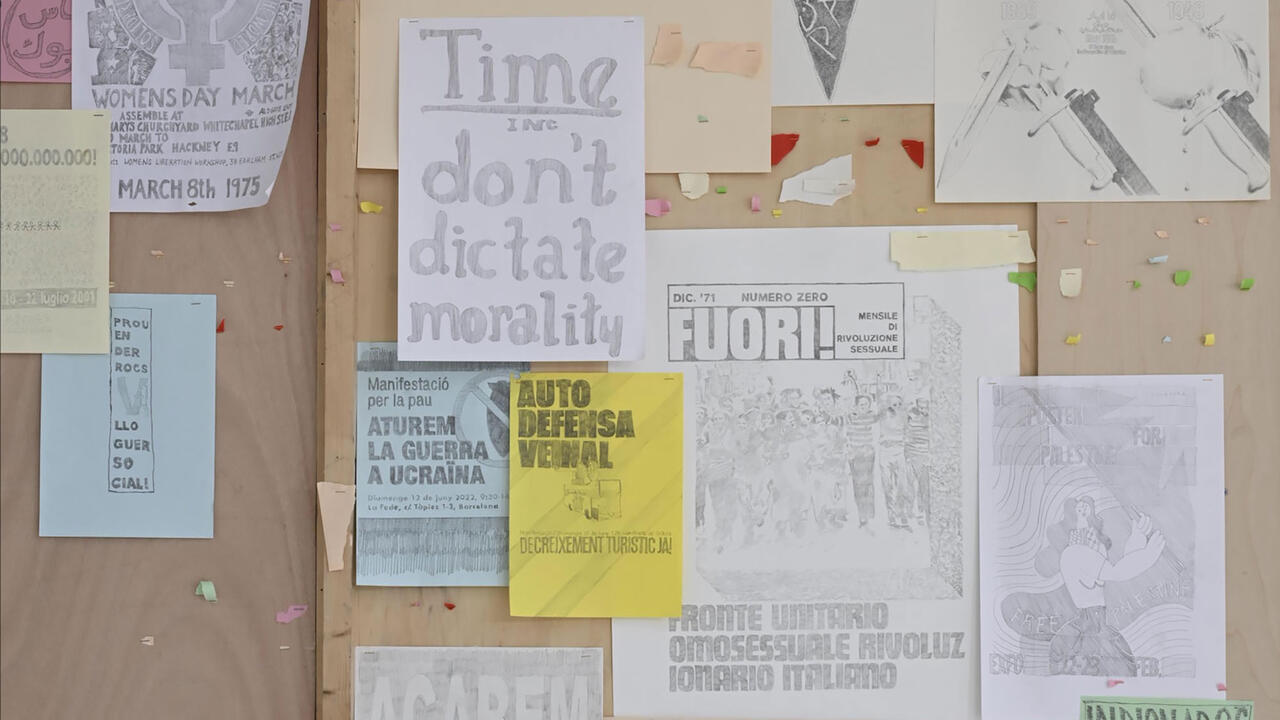

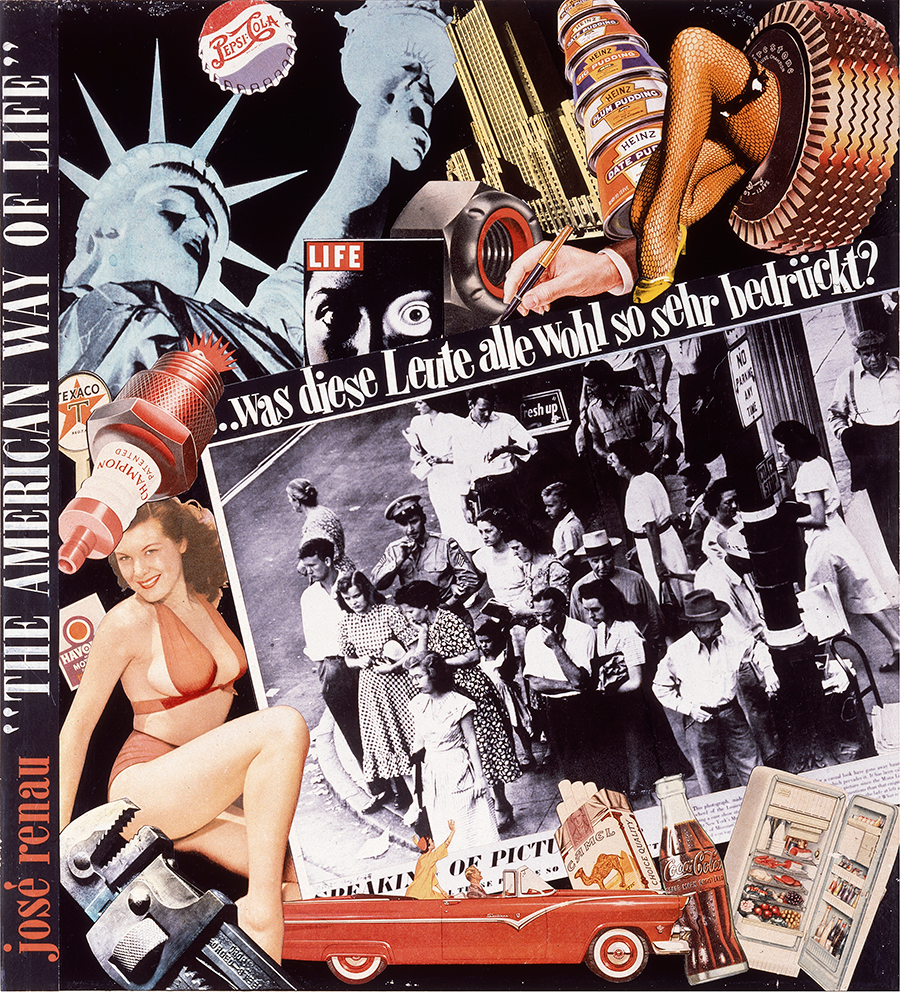

When I visited IVAM last spring, its anniversary-year programme was in full swing, and its forthcoming exhibition schedule was taking shape: future shows include presentations by Mona Hatoum, Gülsün Karamustafa and Zineb Sedira. The institution is manifestly striving to redress its historical gender disparity and, while its examination of its distant past overlooks its more traumatic recent one, it is striving to create new mythologies for its future. Comics – a practice with a strong tradition in the city – weave throughout the flagship exhibition, ‘Times of Upheaval: Stories and Microstories in the IVAM Collection’, and include Carlos Giménez’s 36–39 Malos tiempos (36–39 Bad Times, 2007–09), a graphic novel which follows the Spanish Civil War through the experiences of ordinary people. Moreover, juxtapositions between, for instance, Martha Rosler’s series ‘House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home’ (1967–72/2004–08) and ‘The American Way of Life’ (1966) by political propagandist and Valencia exile Josep Renau, both cut-and-paste representations of the commerce of violence, similarly demonstrated the collection’s distinctive capacity for igniting idiosyncratic dialogues that draw from the city’s artistic history.

Earlier this year, IVAM’s extensive exhibition ‘1989. The End of the 20th Century’ deployed artworks to represent a cross-section through what was a pivotal year for geopolitics, at least from a European perspective, which coincided with the museum’s founding. It was also a year that, in arguably marking the transition from the modern to the contemporary, also makes the M of IVAM permanently out of synch. In looking back over 30 years, past its own times of crisis and hiatus, the IVAM of the present is, counterintuitively, embracing anachronism and turning outmodedness into a productive, creative strategy. The anniversary programme is, therefore, not so much a celebration as a therapeutic intervention by which the institution is re-examining its origins, re-establishing an ethics of public service and cautiously positioning itself in the cultural landscape of renewal in which Valencia now finds itself.

Although IVAM’s watchwords often seem drawn from a 1990s discourse of globalization, Cortés explained to me that he thinks it makes little sense for him to aspire to run it as a global museum. One expression of this – his idea that IVAM focuses on the sociocultural topic of the Mediterranean – suggests that it will have to grapple with what has since become a tragic graveyard for migrants, wresting the narrative from sun-sea-and-sand, despite the tourists that flock to the city. Manuel Segade directs Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo in Móstoles, Madrid, one of the most recent additions to the landscape of public museums in Spain, which opened in 2008. ‘Valencia is a city with a huge population and a cultural scene that is very alive,’ he recently wrote to me. ‘IVAM blossomed in the 1990s because of that amazing context and it is happening again right now. It faces the challenge of transforming itself with new forms of institutionality, but the great thing is that a history is already there and a very important collection is already constituted.’

A recurrent criticism when IVAM opened was that the building was oriented in such a way that it ‘turned its back’ on the city centre. Císcar later turned it on its head. Looking to the future, Cortés plans to crown the anniversary year with the transformation of a conjoining square into a green space for the barrio. Jiménez Landa is among the commissioned artists. He brings his uncanny ability to connect farce and fable, disillusionment and hope, through a genial form of institutional critique. One of his works will consist of a lamp that will illuminate whenever someone opens the refrigerator of the IVAM staff kitchen: both a distress signal and a reassuring wink.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 207 with the headline ‘House on Fire’.