Rosalind Brodsky Finds Herself Under the Hexen’s Spell

At CHELSEA Space gallery, Suzanne Treister’s alter ego delves into the murky world of the occult

At CHELSEA Space gallery, Suzanne Treister’s alter ego delves into the murky world of the occult

One theory has it that anyone can trace a connection to anyone else on the planet by no more than six degrees of separation. Depending on how you look at it, this can either be taken as proof of the comfortingly small world in which we live or give a vertiginous view of the infinitely overlapping networks of people and places that, in our understanding of the world, we struggle to keep separate. If everyone (and everything) can be so easily interlinked, an active imagination can quickly trace lines of causality that play fast and loose with orthodox historical narratives, finding conspiracy and shadowy sub-plots where previously there was only coincidence.

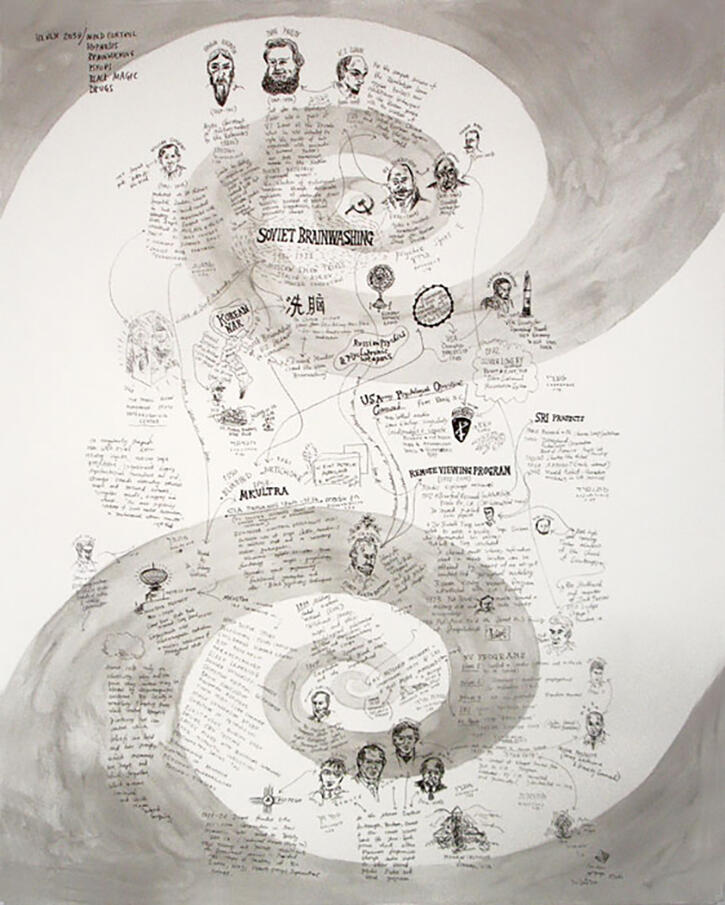

One such imagination belongs to Rosalind Brodsky, who believes herself to be a time-travelling researcher employed by IMATI, the Institute of Militronics and Advanced Time Interventionality. Another belongs to the artist Suzanne Treister, who invented Brodsky as her flamboyant alter ego in 1995 and whose latest project, ‘Hexen 2039’, comprises an exhibition, a website, a book, a film and interventions within the collections of existing institutions. The bulk of the project exists as series of drawings, which, along with a display case of associated ephemera, were displayed in CHELSEA Space gallery (moving to New Art Gallery Walsall this Spring). These works sought ostensibly to demonstrate Brodsky’s belief in the involvement of military intelligence and the entertainment industry in the murky world of the occult.

To give one example (a full account of Brodsky’s elaborate web of cross-references would fill pages), she notes that the US Military Academy at West Point provided the set for the witch’s tower scene in The Wizard of Oz (1939), accompanied by composer Modest Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain (1867) and released by MGM on the eve of World War II. The same piece of music was also used a year later for a sequence in Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940) featuring a creature called the Chernabog, originally a Slavic black god of death, who lent his name to the Ukrainian town of Chernobyl. Mussorgsky’s bald mountain is in fact Mount Triglav in Slovenia, which, according to pagan tradition, is the gathering place of Satan and his followers. Did I mention that Samuel Goldwyn of MGM was suspected, along with much of the Hollywood film industry, of involvement with Aleister Crowley’s occult group the Ordo Templi Orientis? According to Brodsky, so too were the US and British intelligence services.

These fascinating (if occasionally spurious) links recur in Treister’s (or Brodsky’s?) rangy and somewhat manic diagrams, which, in their overexcited urgency to persuade, also allow doubt to creep in. Unlike the confidently elegant drawings of fellow conspiracy theorist Mark Lombardi, it is in these works that the presence of our unreliable narrator is felt most strongly. Little biographical information is given about Brodsky; she serves primarily for Treister as an added layer of removal between the artist and the work, making it harder for us to gauge her faith in the material with which she is dealing. Treister’s ‘Graphites’ are a series of rather more matter-of-fact renderings of key points of reference. A small notice explains, however, that the drawings have been subjected to electrical currents which, with the aid of an ‘Electroencephalographic Current Converter’, are converted into inaudible ‘frequency groups for use in psychological operations equipment’.

Marginally more convincing were the ‘Remote Viewing Drawings’, made in the presence of Dr. John Dee’s ‘scrying crystal’, owned by the Science Museum in London. ‘Intelligencer’ to Queen Elizabeth I, Dee was a close associate of Sir Francis Walsingham, the notorious Elizabethan spymaster, but he was also a mathematician, alchemist, mystic and an influence on the young Aleister Crowley. Dee claimed that his crystal, given to him by angels, revealed images of spatially or temporally distant places and events in its semi-reflective surface. This technique, known as ‘scrying’, is now referred to as ‘remote viewing’ by psychics, mediums and the US military, who experimented with it as recently as 1995. Treister’s attempts at ‘scrying’ showed tentative outlines of buildings, faces and diagrams, which in their uncertainty achieved a sense of sincerity only slightly undermined by the occasionally preposterous subject matter (a cross-section of Samuel Goldwyn’s brain revealing palm trees and a rainbow, for instance). In the Science Museum itself, next to cramp-rings, a ‘prognosticator’ and a unicorn horn, Treister had inserted her own ‘Graphite’ of Dee’s crystal in place of the real thing, which, a label explained, had been removed for conservation.

‘Hexen 2039’ succeeds, like Dee’s device, by its semi-reflectivity. When Treister’s presentation of material becomes too transparent, it begins to falter, as with the video accompanying the project, in which recognizable art-world figures, posing as ‘experts’, are shown awkwardly over-enunciating unfamiliar and scripted dialogue. When, however, we find ourselves wondering about Treister’s investment in Brodsky’s speculations while simultaneously beginning to entertain them ourselves, we are under ‘Hexen’’s spell. After all, in an age when religious fundamentalism and alternative belief systems are on the rise and faith in post-Enlightenment progress is on the wane, perhaps Treister’s attention to old-fashioned arcana points to the nature of our not-too-distant future.

Main image: Suzanne Treister, Rosalind Brodsky in her Electronic Time Travelling Costume to rescue her Grandparents from the Holocaust ends up mistakenly on the set of Schindler’s List, Krakow, Poland, 1994, from the project ‘Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky’, 1997, digital print, 50 × 70 cm. Courtesy: the artist, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York