Salon Selectives

How open are open calls?

How open are open calls?

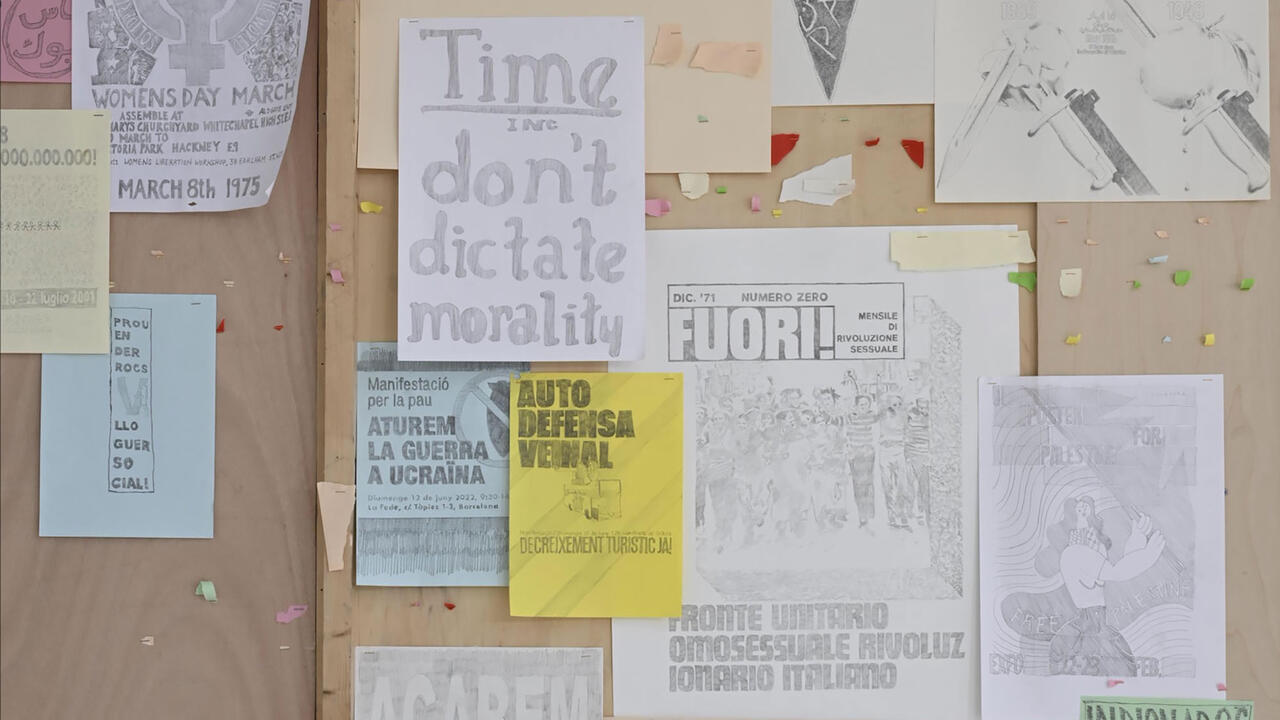

The open call for artists has been used as a procedure for convening exhibitions for centuries. The Salon de Paris became a public event in 1737 and London’s Royal Academy of Arts has held its Summer Exhibition every year since 1769. In other words, the juried competition long predates the mid-20th-century emergence of institutional artistic direction and curatorial authorship as templates for the selection of artists and the choosing of works of art for public display. Yet, as the submission of paper portfolios and 35 mm slides has given way to PDF entries and file-sharing, the skeuomorphism of the salon format and its panoramic approach has had an uneasy transition into the present. In the UK, for example, witness the skittish evolution of the Whitechapel Gallery’s 1932 East End Academy into the current London Open triennial exhibition, or the reheating in various guises of New Contemporaries, which dates back to 1949.

Meanwhile, in the field of architecture, the last few decades have seen the open call mutate into an administrative instrument of daunting reach. With persuasive assertions about open-to-anyone opportunity and the rewarding of aspiring-yet-undiscovered talent, the call for proposals is the go-to mechanism by which publicly funded projects show themselves to be diligently transparent and privately backed commissions promote themselves as meritocratic. Yet, for all its pains to be apolitical and to counter perceived favouritism, the open call is often a procedural masquerade.

While competition organizers typically trumpet the volume and cosmopolitanism of applications received as an ebullient endorsement, others may rue the sheer amount of collectively wasted effort made by the also-rans. (In Spain, Bilbao-based studio Taller de Casquería estimated that the hours involved in the 1,715 submissions received for the Guggenheim Helsinki open call for designs represented over €18 million worth of speculative work.) In Gary Hustwit’s 2011 documentary film, Urbanized, Rem Koolhaas stated that such competitions were a ‘complete drain of intelligence’, inviting mass creative thinking with the guarantee that the vast majority of it will be discarded. This addiction in the field of architecture appears to be gaining traction in contemporary art as a means not only of generating exhibitions but of programming institutions.

A notable example: in 2013, the Qatar Museums authority and Fondazione Prada launched Curate, a global curatorial competition – with a jury including Koolhaas, Hans Ulrich Obrist and former Moroccan athlete Nawal El Moutawakel – that tellingly offered an architectural metaphor as it announced that three selected exhibition proposals had won the ‘chance to break new ground’; none have yet begun. On a different scale, since 1998 the New York non-profit stalwart apexart has invited applications for what it curiously refers to as its Unsolicited Exhibition Program. The open call attempts to stymie any doubts about the transparency of the way in which the resultant exhibitions are selected by, in recent editions, taking the process to an administrative extreme. Short submissions are anonymized and ranked by a crowdsourced jury of several hundred people.

Meanwhile, Antwerp’s Extra City Kunsthal has recently replaced its director-curator, Mihnea Mircan, in favour of a programme for 2017–19 that will be entirely realized on the basis of proposals that have been submitted to an open call. Likewise, writing as I am from the perspective of Barcelona, the Fabra i Coats Centre d’Art Contemporani – which was established in 2012 – has never had an artistic direction team; instead, the curating of its galleries is put out to tender each year. This mission creep of the open call from being an episodic incentive to a wholesale tool of institutional rationalization might seem benign. In Antwerp, there is doubtless a well-meaning desire to have a neighbourly institution. In the Barcelona context, the particular enthusiasm that art centres have for open calls may, in some respects, be an overcompensation for the spectre of cronyism and string-pulling that lamentably haunts the awarding of public works contracts in Spain.

Yet, pondering more generally, and setting aside what are often positive outcomes, the crude tool of the open call can result in alarmingly unexpected systemic consequences. There is a danger of downgrading the artistic or curatorial direction of art institutions to the mere meting-out of funding in a remote demonstration of reasonable-ness, charity and perpetual presentism, in which long-term research, fieldwork and collegiate relationship-building are degraded.

The open call mechanism might actually exacerbate the precarious situation of the artists and curators it is supposed to assist, as they dedicate more of their labour speculatively in the hope of success. Of course, everyone chosen from an open call actively wanted to be a part of the competition. Yet, there is a whole gamut of artists who – no matter how important their work, and for myriad reasons – cannot or do not want to join in. The open call can only receive compatible information and, for all its intentions to be an instrument of opportunity, is often a deleterious habit that excuses short-sightedness and, counterintuitively, creates a closed loop. If this paradox of the open call suggests it is a rudimentary operating system, then it should be all the easier to hack.

Main image: Felicien Myrbach-Rheinfeld, Candidates for Admission to the Paris Salon, c.1900. Courtesy: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.