Five Writers Celebrate the Work of Sarah Lucas

A retrospective at Tate Britain showcases the YBA who defied good taste and mocked sexual norms

A retrospective at Tate Britain showcases the YBA who defied good taste and mocked sexual norms

Hettie Judah

‘Bunnies’ (1997–ongoing)

A nylon tumult of lust, vulnerability, assertiveness, polygendered anatomy and a confusion of fuck-me/don’t-touch-me vibes, Sarah Lucas’s ‘Honey Pie’ opened at Sadie Coles HQ just as the world shut down in early 2020. A sculpture show, yes, but also an installation teasing taste, class and the politics of design. Arranged on four sides of a raw concrete divider stationed in the middle of the gallery (so butch!), contorted lady-shapes knotted from stuffed and painted hosiery writhed and sprawled around modernist chairs. The chairs were classic, collectible, bland good taste. The Saturday night shoes worn by the hosiery sculptures (which carried titles like SUGAR or DORA LALALA) looked like they’d been picked up at a south London street market.

Here, Lucas’s ‘Bunnies’ (1997–ongoing) had evolved by way of her tangling ‘NUDS’ series (2010) and the troupe of plaster-cast female body parts that populated her British Pavilion installation ‘I Scream Daddio’ at the 2015 Venice Biennale. In its tits-out anxiety, both brazen and bashful, ‘Honey Pie’ was a slouching chorus to the sexual politics of the moment. This was fresh after #MeToo, when grown-up female sexuality didn’t quite know where to put itself, but the night tubes were full of young girls in toe-crushing platform shoes, raven lashes and contouring.

The previous year, Lucas had designed a tribute to Franz West at Tate Modern. She invited his spirit into ‘Honey Pie’: he’s there in the unyielding, artificial colour of the plinths – Capri-Sun orange, Hubba Bubba pink, Aquafresh blue. He’s there, too, in the wink-wink obscenity – the lumpen turdy cock forms rearing out of diminished hosiery crotches. If West is the show’s dirty daddy, Louise Bourgeois is its wicked mama: Lucas’s soft sculptures (and their cast-bronze sisters) bristle with many breasts in an ancient abundance. The accidental isolation and emptiness of ‘Honey Pie’ was curiously appropriate: Lucas’s sculptures look as though they’re waiting for us, on display, like working girls in the world’s loneliest brothel.

Daisy Lafarge

The Old In Out (1998)

In Sarah Lucas’s The Old In Out (1998), an otherwise immaculate cast of a toilet bowl is imperfected by a series of messy drips at the back: the traces of resin-pouring moonlighting as beatified piss. It was shown among a fleet of nine resin toilets, their tones ranging from mild dehydration to UTI to liver disorder. They lack plumbing but, being vessels, they are kenotically begging to be filled. I think of them as bodies, of the body’s faulty plumbing. I also think of the late American poet Hannah Weiner, who spent a week sitting in a sink to experience the mystical economy of pissing and drinking simultaneously. In Love’s Work (1995), philosopher Gillian Rose described shit as ‘the hourly transfiguration of our lovely eating of the sun’, and Lucas’s sculptures gleam with this solar intensity. To my eyes, they are creaturely, snail-like, beautiful.

I wish I’d seen this work when I most needed it, which was in 2011, the year I started art school. Like most first-year students, I had a toilet phase: I loved Helen Chadwick’s Piss Flowers (1991–92) and the video Pipilotti Rist installed in the toilets of her solo show at London’s Hayward Gallery in 2011. I was reading Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye (1928) and Angela Carter’s The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography (1978). Lucas’s work escaped my attention because, by that point, anything adjacent to the young British artists (yBa) – with the exception, perhaps, of Rachel Whiteread – had become something of a slur in art school. It was an aesthetically challenging time. Relational aesthetics had come and gone, and all the hotshot boys in my year amused themselves by marionetting its corpse. The result was a kind of artisanal pun-based conceptualism, which found its textual equivalent in alt lit.

In art history, I learned that female yBa artists were the disobedient, feminism-rejecting daughters of the second wave, so I obediently rejected them in turn. Now I see that blanket treatment as a disservice. The Old In Out lifts its title from a slang term for sexual intercourse. In Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange (1962), it’s a term for rape. Lucas’s toilet series is sharp and unsentimental, grappling with gender and class violence while also eliding any easy bond of solidarity with a second-wave sisterhood.

Ten years on from art school, this disjuncture still interests me. Although I’m less compelled by art-historical redressals that amount to adding an overlooked artist back in, Lucas’s work was more overly looked-at than overlooked, resulting in the lack of nuanced engagement that hypervisibility often entails. I still hope to see this work in the flesh, and to watch the light animate its stained-glass creatureliness, since animals are the only ones, really, who know how to handle their shit.

Princess Julia

Oral Gratification (2000)

In February 2000, I walked into Sarah Lucas’s ‘The Fag Show’ at Sadie Coles HQ on Heddon Street in London. Now, I loved a cigarette in those days; in fact, I was as obsessed as the actress June Brown, who was known for her chain-smoking portrayal of Dot Cotton on EastEnders (1985–ongoing). June once told me she wanted to stage a pro-smoking march across the Millennium Bridge in 2007, when the smoking ban was introduced in UK workplaces. Obviously, I was roped in. Just like June and me, Sarah liked a chuff and, since the age of nine, she apparently coveted those decadent and highly addictive smokes with fervour. Just like fags themselves, I was instantly hooked on Sarah’s take, but it was the ciggie-encrusted tits of Oral Gratification (2000) that really struck me. At ‘The Fag Show’, the sculpture was placed against a wall papered with floating repetitions of the cigarette orbs attached to Oral Gratification’s chair. That chair. It’s just a chair, isn’t it? Yet, once Sarah adds appendages to her chairs, everything comes to life. The ciggie tits resonated with me; they made me laugh, but they sort of made me cry, too. Sarah gave up smoking around this time. There are a few variations on the theme in the show, but Oral Gratification feels stark, confrontational in comparison to the earlier black bra-clad version of the sculpture, Cigarette Tits (Idealized Smokers Chest II) (1999). In an interview with the curator James Putnam, she said: ‘There is this obsessive activity of me sticking all these cigarettes on the sculptures […and] obsessive activity could be viewed as a form of masturbation.’ I get that, actually: smoking is obsessive. Smoking has always been marketed as an alluring activity. Addicted to fags, addicted to sex; the two went hand-in-hand. Oh, and that post-coital puff! Well, I did do a stint at Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous. I’m getting all these parallels, now that I’m really thinking about it. Do you think that’s what Sarah wanted to address? I’ll have to ask her…

Rye Dag Holmboe

Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Freud) (2000)

A red futon mattress hangs by a strap from a metal clothes rail, its side pierced by a fluorescent tube. A lightbulb glows orange in a tin bucket, above which two more lightbulbs dangle from a coat hanger, like eyes out of their sockets. Alongside lies a cardboard coffin, lit from within. How readily the installation changes register! Ordinary things turn menacing, erotic. A visual pun can be amusing, but the way the work pulls household objects into a less differentiated, more bodily space is also disquieting. You laugh because you are anxious. Lightbulbs turn to eyes turn to testicles or breasts and back again; the tin bucket becomes a belly with a bulb-baby inside it; a fluorescent lamp morphs from the holy lance to a finger to a penis. A mattress-Christ pierced through his side. The great masochist. I think of Pontius Pilate. Of Saint Lucy, with her eyes on a plate. Of the incredulity of Saint Thomas. I also think of the work of Marcel Duchamp, Tracey Emin, Dan Flavin. And, of course, of Sigmund Freud, in whose bedroom Lucas’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Freud) (2000) was first installed. You wonder what animates the interior of the cardboard coffin, what sets the dream in motion. For Freud, what resided ‘beyond the pleasure principle’, as he noted in his 1920 essay, was death. Desire, always in excess of need, is underpinned by the compulsion to repeat. To live is to die, too, and all of us, according to Freud, yearn to return to the inertia of inorganic life. If desire is preceded by the loss of the original object and the experience of frustration then, in the unconscious, death is nirvana: an undifferentiated space where desire is abolished because it is definitively fulfilled. Lucas’s installation draws you closer to the ground of infantile sexuality and its polymorphic, quasi-hallucinatory nature. It also brings you closer, not to death, exactly, which is unimaginable – like a dream, art must always assume a symbolic form – but to the life-in-death of inanimate things and the death-in-life of animate things.

Jack O’Brien

Perceval (2006)

I have a strange relationship with Sarah Lucas’s Perceval (2006). I first encountered the work in my early teens, after my family moved to Suffolk. Garishly glossy and monumental, this life-size bronze replica of a horse and cart – the artist’s only public sculpture – has appeared across the globe, from Central Park in New York to Aspire Park in Qatar. However, my Perceval stood on the quiet grounds of Snape Maltings Concert Hall, not far from where Lucas herself now lives.

I hadn’t given much thought to this work until a few months ago, when I stumbled upon a miniature cart with gold-trimmed wheels lying amongst a pile of trash and domestic debris outside my London flat. This porcelain ornament – featuring a shire horse pulling a wooden carriage, often laden with miniature barrels or other paraphernalia – was once a popular knick-knack in British homes. It served as the inspiration for Lucas’s sculpture, in which the horse and carriage are accompanied by two of her signature giant concrete marrows.

For some, Perceval is a beloved character from ‘the good old days’ who might induce nostalgia for a bygone era of a less modern Britain. For others, that same era was one of class division and racism to which they wouldn’t seek to return. Watching benevolently from the side-lines, Perceval – named after a knight from King Arthur’s legendary court – has witnessed the decline of New Labour under former prime minister Gordon Brown, followed by the rise in 2010 of austerity measures under David Cameron’s Conservative coalition. He is a relic from the pre-Brexit era, from the decade before division, disillusionment and precarity spiralled out of control. The Britain that the ornament stood for is fading fast.

Like the little carriage I found discarded in the trash, time rolls on. Yet, Lucas finds a way to make us stop and reflect. She created a monument that, lumbering under the weight of its concrete marrows, remains stoic. Through elevating this forgotten ornament into the realm of contemporary art, Perceval is Lucas’s way of deconstructing class. For an artist whose practice has often and boldly embraced metaphors of sex and death, this perfectly likeable work might appear somewhat tame. Yet, it is Perceval’s connection to a place and time that no longer exists, and perhaps never did, that makes it as evocative as any of her sculptures.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 238 with the headline ‘Crash a Fag’

Sarah Lucas’s ‘Happy Gas’ is on view at Tate Britain, London from 28 September until 14 January 2024

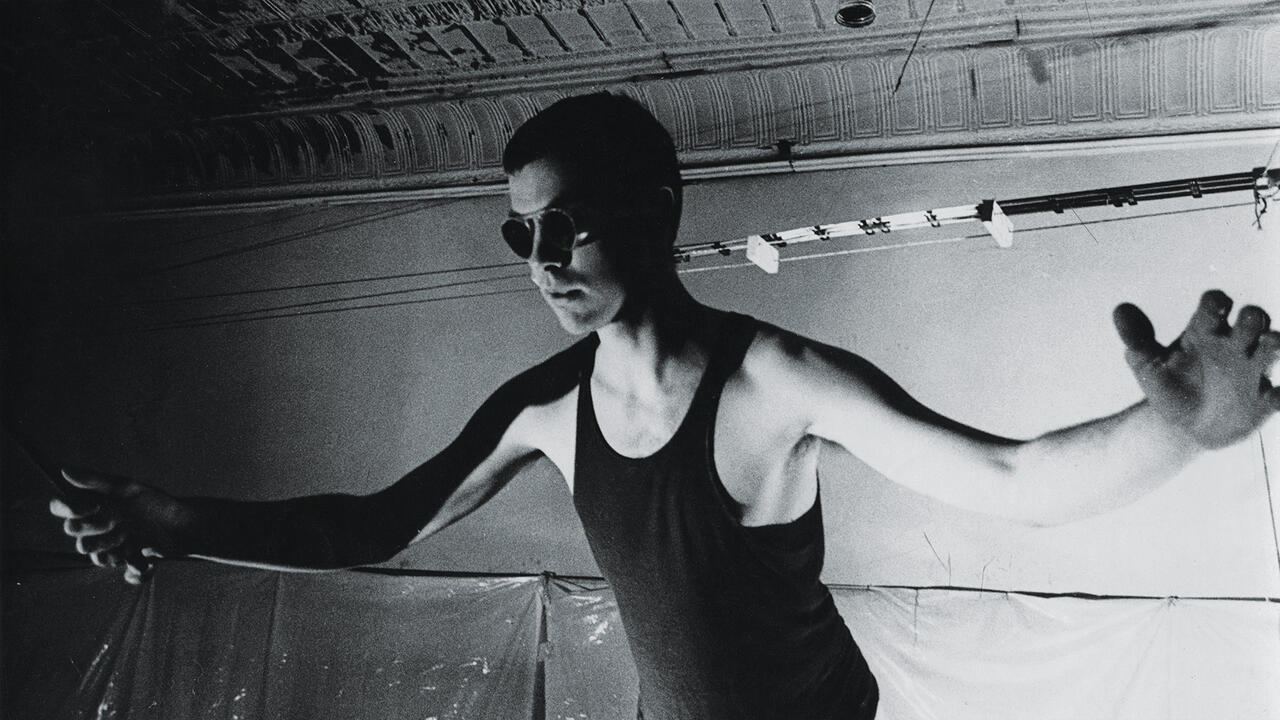

Main image: Sarah Lucas, I SCREAM DADDIO, 2015, installation view. Courtesy: © Sarah Lucas, British Council and Sadie ColesHQ, London; photograph: Andrea Rossetti