Searching for a New Intimacy at London Contemporary Music Festival

When musical signifiers for sex so often become sonic pornography, LCMF 2017 showed alternative ways of marrying sound and body

When musical signifiers for sex so often become sonic pornography, LCMF 2017 showed alternative ways of marrying sound and body

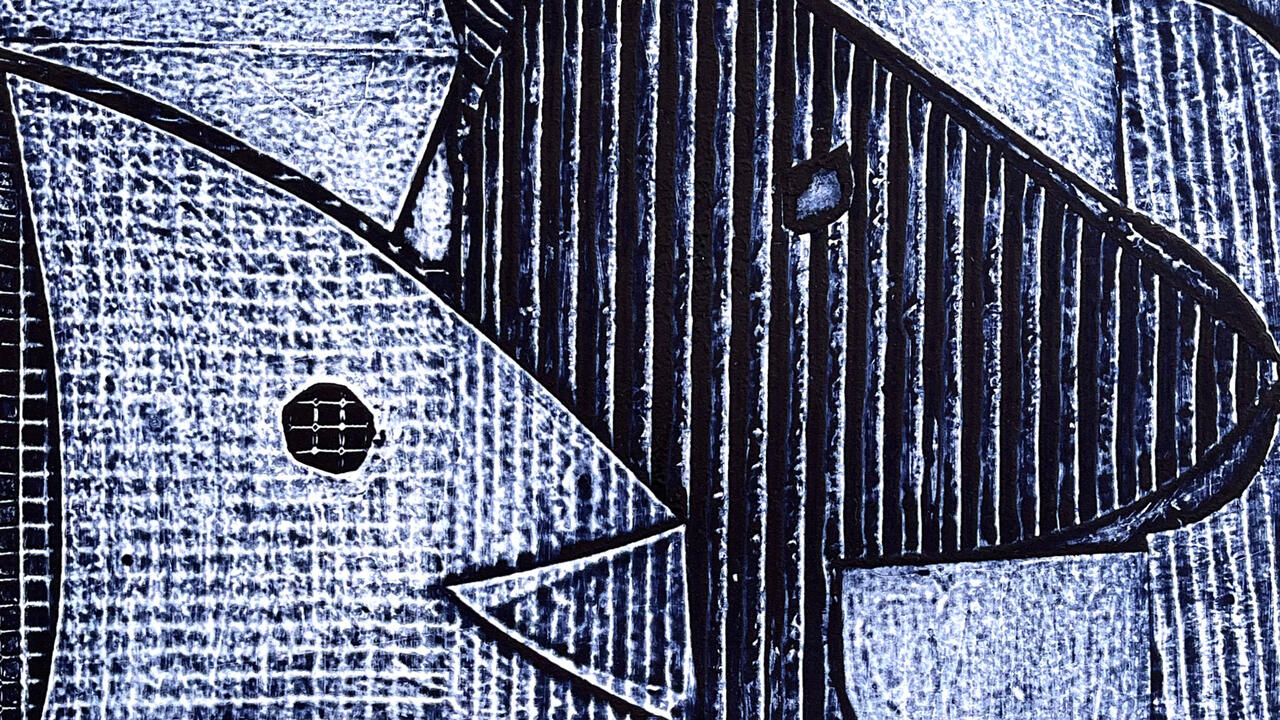

During a screening at this year’s London Contemporary Music Festival of a 1967 film, Fuses, in which the composer James Tenney has sex with his wife the artist Carolee Schneemann, some very old assumptions about new music were upended. Modern composition is sexless, cerebral and privileges arithmetic over melody. I don’t like new music because where’s the passion – where is the emotion? That narrative too often prevails. But Fuses inaugurated a sequence of concerts at the LCMF – collated under the banner ‘The New Intimacy’ – that set out to prove otherwise.

Since its founding in 2013, the LCMF has thrashed around looking for an identity. But the festival surely came into its own last year with a special focus on the New York experimental composer Julius Eastman. LCMF shone a spotlight on the all too brief career of an enigmatic figure whose boundary-pushing open-plan scores and their loaded titles (such as Gay Guerrilla, Crazy Nigger and Nigger Faggot) riled against a new music mainstream that he considered white, middlebrow and palpably lacking in ambition. This year, the LCMF’s artistic director Igor Toronyi-Lalic pieced together an uncompromising programme that unpicked another secret history of new music. Sex, as we know, sells. But dropped into the cavernous space of Ambika P3 at the University of Westminster, audiences were made to think again about composers and their relationships to sex and intimacy.

Toronyi-Lalic’s programme note argued that by ‘seeking universals, abstracts, objectivity’, musical modernism largely rejected the body, which is arguably a sweeping statement. Luciano Berio’s 1961 electronic classic Visage manipulated voice recordings of his wife – the singer Cathy Berberian – and hearing her groans as anything other than orgasmic is impossible; the nervy, twitchy vocal utterances of György Ligeti’s music-theatre pieces Aventures (1962) and Nouvelles Aventures (1965) were essays in bodily energy; and the composer Sylvano Bussotti relished baiting sexually repressed new-music types with explicitly erotic settings of the Marquis de Sade. Bussotti, it is said, had Pierre Boulez in mind – a composer whose music, rightly or wrongly, has become synonymous with the idea of a dispassionate modernism.

Experiencing Carolee Schneemann’s film Fuses (1967) left some intriguing questions hanging. Had the participants not been a composer with a fascination for intricate tuning systems (Tenney) and a visual artist (Schneemann) whose work offered a feminist critique of modernism (which, she thought, was embarrassed by female sexuality), would the film be pornography, pure and simple? Some of the metaphors, five decades on, feel decidedly quaint. Nude bodies, buttocks bouncing, run into the sea; close-ups of Schneemann’s pubic hair merge into soft-focus footage of the couple’s cat, Kitch. But lingering camera shots of Tenney’s erect penis, and of the inside of Schneemann’s vagina, proudly parade the pair’s lack of concern about taboos.

The screening of Fuses was followed by Tenney’s 1978 string quartet Saxony, performed with fingertip sensitivity by the new music ensemble Apartment House, led by cellist Anton Lukoszevieze. The concept governing Tenney’s quartet – notes slipping away from the standard way string instruments are tuned to generate a hovering, trembling whirr which grows in intensity without ever hitting a point of climax – locks the listener into a state of unbroken bliss. The Second String Quartet by the Swiss composer Jürg Frey, which he completed in 2000, also focuses the ear on sounds so tactile and sculptural that you could reach out and touch them. Except that Frey embeds a teasing twist: his sounds play hard to get by bordering on inaudibility. Only by listening with increasing levels of concentration can the listener enter into an intimate communion with the fluctuating nuances of his notes.

LCMF’s ‘New Intimacy’ series also saw the composer Pauline Oliveros – who visited the festival in 2015 and died last year – represented with The Sluts and Goddesses Video Workshop – Or How To Be A Sex Goddess in 101 Easy Steps, a 1992 film by the artist Annie Sprinkle and Maria Beatty (described as a ‘feminist porn pioneer’), which Oliveros scored with pumping and throbbing drones. Elsewhere, the UK premiere of Kajsa Magnarsson’s Testet-Vinklar (2013), billed as a piece about sexual objectification and identity, felt woefully lightweight because the squelchy sonic consequences of Magnarsson bopping around in fetish rubber lacked substance. But Tape Piece (2012) by Maya Verlaak and Andy Ingamells achieved something meaningful for both ears and eyes as these two composers rolled around the floor, ripping sellotape off each other’s (clothed) bodies. The falsetto squeals of the sellotape launched fragmentary melodies into the air. This piece was witty and fun.

Nothing, perhaps, defines a new music geek like someone who, when confronted with pornography, worries about the nature of musical material. But the concentration on sound these concerts presented told us that those usual musical symbols for sex – chord sequences hurtling towards climaxes crowned by cymbal crashes, like so many corks popping out of Champagne bottles – can, in the wrong hands, be a sort of sonic pornography in itself, leaving sound objectified and caricatured. Work by Tenney, Frey and Oliveros all demonstrate other ways of marrying sound and body. Now sound isn’t symbolic of anything beyond itself and its reverberating majesty can transform the chemistry of your body – if you’re prepared to give it the chance.

Main image: Carolee Schneemann, Fuses, 1964-1967, 16 mm (colour, silent), original film burned with fire and acid, painted, and collaged, 29:51 min, film still. Courtesy: Carolee Schneemann, Galerie Lelong & Co., and P•P•O•W, New York; © Carolee Schneemann