The Shows to See During New York Pride

On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, the shows to see around the city that contend with LGBT culture and political history

On the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, the shows to see around the city that contend with LGBT culture and political history

‘Art After Stonewall: 1969–1989’

Leslie-Lohman Museum and Grey Art Gallery

24 April – 20 July 2019

This sweeping exhibition, split between two compact venues, traces the artist responses to the Stonewall Riots of 1969 and the various convulsions of queer politics up to the darkest years of the AIDS crisis. The starry presentation at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery features Andy Warhol’s portrait of transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson and Greer Lankton’s bewitching femme puppets, as well as a wealth of ephemera from the health campaigns of ACT UP, from the infamous ‘Silence = Death’ t-shirt to Keith Haring’s painting of mutual masturbators, Safe Sex (1988). For me, though, nothing beats Martin Wong’s Big Heat, painted that same year: two Bronx firemen kiss, clad in their black rubbers, as a rainbow begins to blush on the precisely rendered bricks of a tenement behind them – a powerful scene of love amidst the ruins of the 1980s.

Wong’s penmanship is showcased at Leslie-Lohman, where his poster drawing for The Cockettes, the legendary drag troupe, shows a hippopotamus belching the stars of the Chinese flag. The works here, mostly from the 1970s, trace the initial exuberance of the riots, in a sparkling 1969 assemblage by Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, to the feminists’ break with the male-dominated Gay Liberation Front, embodied by the piercing gaze of Kate Millett, author of Sexual Politics (1970), in a 1970 painting by Alice Neel. Millett’s own monumental sculpture, Approaching Futility (1976), nearly reaches the gallery’s ceiling; a fabric figure scales a ladder in a wooden cage, but cannot ascend high enough to escape her prison. Women are still fighting for the same thing.

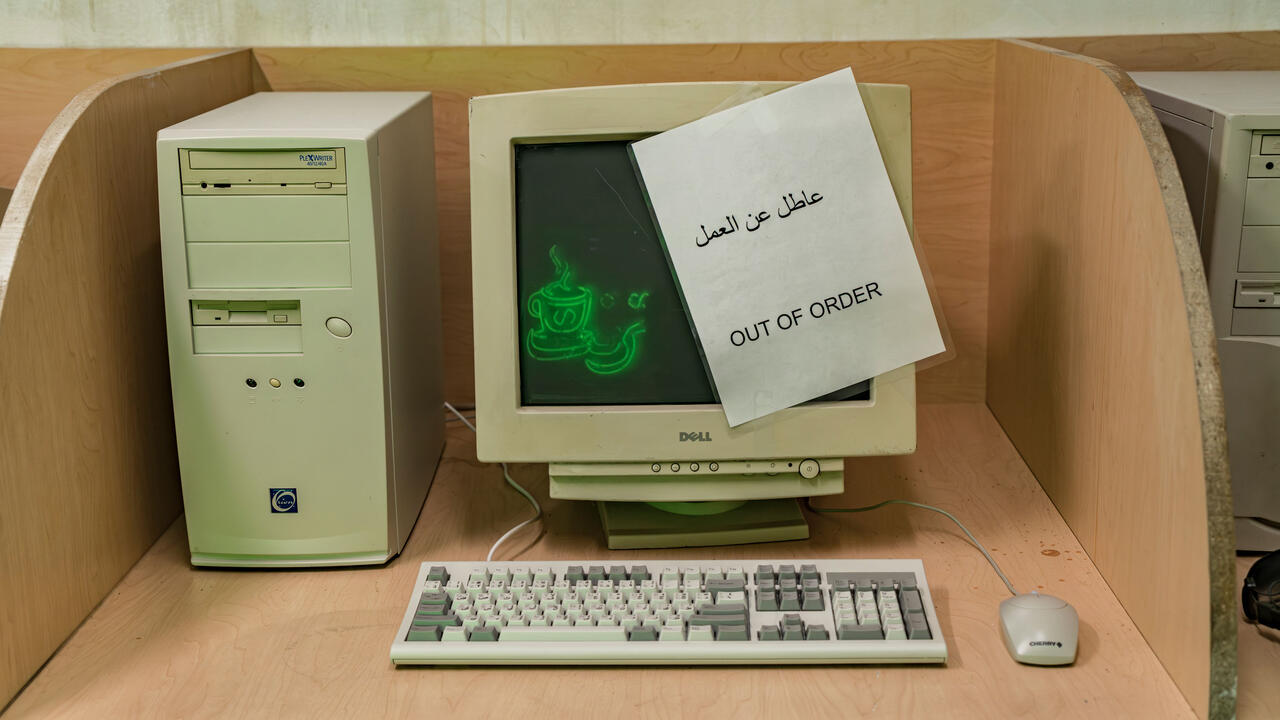

‘Letting Loose: LGBTQ Nightlife Before and After Stonewall’

New York Historical Society

24 May – 22 September 2019

Before the riots, the Stonewall Inn was owned and run by the mafia, who tolerated the queers that congregated there, but made no effort to curb police raids. (In the ’80s, Stonewall was briefly a bagel shop; it is now a National Monument.) It’s fitting that the LGBT revolution began at a gay bar, when dives and clubs were the only places queers could meet and be themselves, safely away from the public eye. This show at the New York Historical Society features a number of surprising artefacts from pre-Stonewall nightlife, such as a matchbook from the Sea Colony, a 1950s working-class lesbian bar in Greenwich Village, as well as a wealth of disco-era ephemera, from merchandise sold at gay male sex clubs like the Anvil and the Ramrod, to the sign for Paradise Garage, where DJ and producer Larry Levan is widely credited with inventing house music.

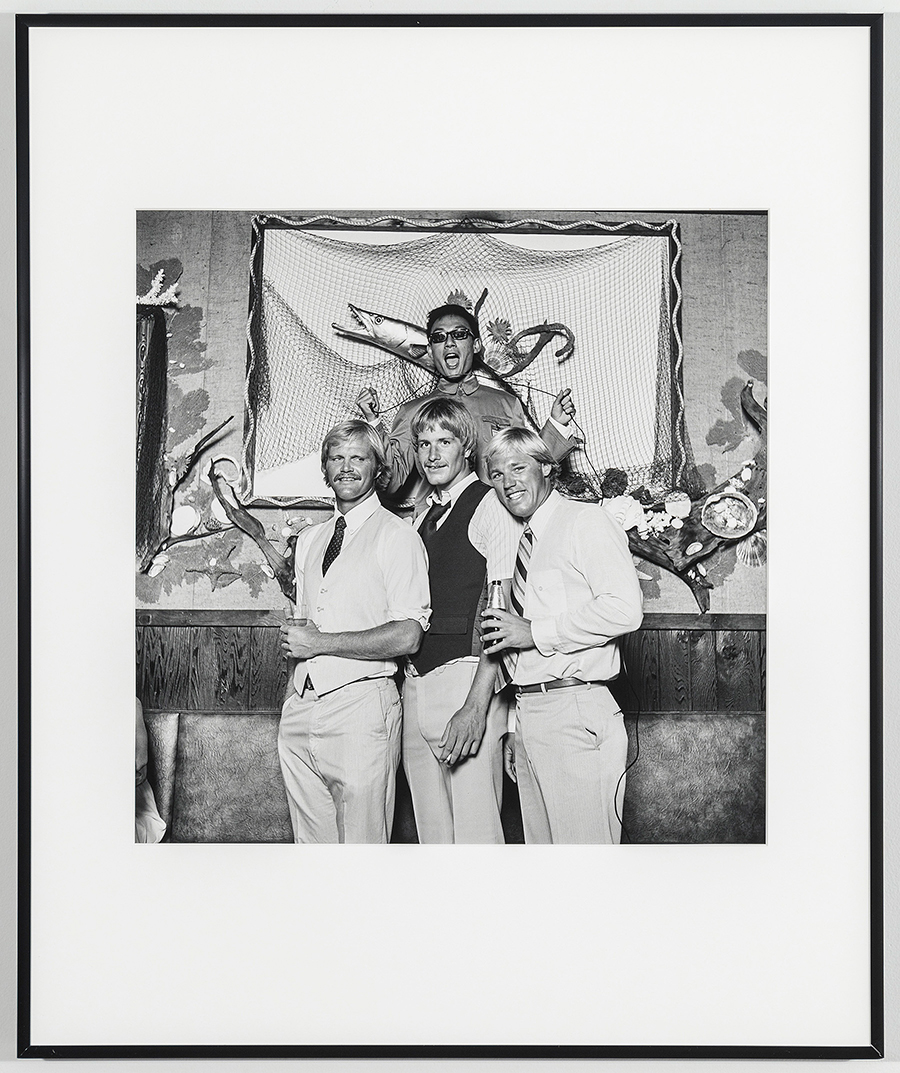

‘Summer of ’82’

Johannes Vogt

5 June – 5 July 2019

Browsing ‘Summer of ’82’, you can almost hear the thump of Taana Gardner’s ‘Heartbeat’, one of Levan’s signature tracks, released just a year before. The show, which examines the early efflorescence of the downtown and East Village art scenes, includes many queer artists, from Martin Wong to David Wojnarowicz and Luis Frangella, who often cruised the crumbling West Side piers for sex and surfaces on which to paint. Tseng Kwong Chi’s wry Lifeguard Ball Wildwood New Jersey (1981) show the Taiwanese artist in Maoist drag — a stereotype of the Chinese tourist before most Chinese had the means to travel abroad — crashing a party of mostly white male beach bums. Marcia Resnick’s 1982 portraits of Klaus Nomi, meanwhile, depict the avant-garde performer just a year before he became one of the first artists to succumb to AIDS.

‘Them’

Perrotin

20 June – 16 August 2019

There’s a spirit of downtown in ‘Them’, a presentation of young queer painters mostly living and working in New York. It opens with Doron Langberg’s Zach and Craig #1-4 (2019), a suite of canvases loosely brushed in pink and orange depicting two men having sex. The show, which aims to showcase ‘sensitive depictions of romance and the poetry of contemporary quotidian queer life’, is strongest when it toys with the notion of the gaze: in Jenna Gribbon’s luminous portrait of a woman, Watching me paint (2019), her stylish suit jacket opened to reveal bare breasts; or Jonathan Lyndon Chase’s Winter Embrace (2017), in which a couple wearing the same bulging parkas, like a pair of poodles, blissfully stare back at us. In two emerald paintings by Salman Toor, young men resemble the figures of late Goya; and in The Bar on East 13th Street (2019), one of them slices a lemon for a cocktail in a reprise of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882). (I couldn’t work out which bar on East 13th, but my bet is on The Phoenix.) Then there’s the show-stopping Fire Island Moonrise (2018), T.M. Davy’s monumental 3.4-metre shoreline pietà, a portrait of the artist and his partner drenched in moonlight so deliciously clear you could drink it like a glass of milk.

‘Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall’

The Brooklyn Museum

3 May – 8 December 2019

Davy’s work also appears in ‘Nobody Promised You Tomorrow’, which features work by artists born after 1969 – though a number of them were born after ’89. Growing up in a climate of increasing acceptance for gay people, these artists examine the ways racism, misogyny and transphobia can intersect with expanded notions of sexual identity. L.J. Roberts’s Stormé at Stonewall (2019) is a monument to the lesbian performer who is credited for first inciting the riots, despite the failure of publications such as The New York Times – quoted here with an erratum that ‘at least one lesbian was involved’ – to acknowledge her contributions. In a nearby assemblage by Juliana Huxtable, a magnetic button announces Africa as ‘The Resting Place of the Gay Agenda’, a nod both to the entrenched racism of many gay men and the colonial-era anti-gay laws still in effect throughout much of the continent. Elle Pérez’s tender portraits of trans and genderqueer friends make fitting company for Felipe Baeza’s tapestry ...el mundo grande (2018), in which an indigo man embraces another whose skin has turned blood red, as a tree sprouts from his open mouth. The work that will haunt me for some time to come, though, is Sasha Wortzel’s This is an Address I, II (2019), a split-screen documentary portrait of homeless queers being slum-cleared from the West Side of Manhattan in the 1990s and early 2000s. According to the Williams Institute, 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBT, a fact worth noting as the Pride March ends this year in the cold shadow of the Hudson Yards.

‘Walt Whitman: Bard of Democracy’

The Morgan Library & Museum

7 June – 15 September 2019

‘Give me interminable eyes – give me women – give me comrades and lovers by the thousand!’ wrote Walt Whitman in 1867. ‘Give such shows – give me the streets of Manhattan!’ We can expect such a scene on Fifth Avenue next weekend, and yet there’s little in New York today that Whitman would likely recognize. (In his time, Hell’s Kitchen was mostly hog yards.) This exhibition looks at the poet who articulated a patriotic ideal perversely interwoven with homoeroticism, most famously in his Leaves of Grass (1855), a first edition of which appears on view here. The show also includes Whitman’s ink-splotched notebooks, and a letter of gushing praise from Ralph Waldo Emerson.

‘Camp: Notes on Fashion’

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

9 May – 8 September 2019

Whitman was much admired by Oscar Wilde, but the two men share very little in style. The latter was a pioneer of ‘camp’, the exaggerated, often ironic, form of expression used as an indiscreet code by gay men for over a century. You may have already heard of this show, which gave this year’s Met Gala its theme – best embodied, perhaps, by Billy Porter, who arrived as Cleopatra on a golden litter, carried by six shirtless men – or even of ‘Notes on Camp’, the 1964 Susan Sontag essay its title references. ‘The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance,’ she wrote, and there’s plenty of that on display: from a pink flamingo Schiaparelli headdress from 2018 to the Marjan Pejoski swan dress famously worn by Björk to the 2001 Oscars. Predictably, there’s plenty of Jeremy Scott, from his obnoxiously branded ballgowns to the cheekier speckled-green leather chaps of a 2012 cowboy ensemble; though more fitting are decadent, voluminous dresses by Vaquera and Paloma that would be at home in the court of Marie Antoinette. Extravagant, too, is the display, which poses each get-up in a glass window, lit with soft pink, as though in a shopfront – a literal gesture of exhibitionism.

Andy Warhol, By Hand: Part II, Drawings 1950s-60s

Sperone Westwater

25 April – 19 July 2019

On the heels of the Whitney Museum’s expansive Warhol survey, this precious show focusses on the most under-appreciated aspect of the Pop icon’s practice. A wealth of drawings here showcases Warhol’s singular draftmanship, but also his acute sense of humour. New to me are life drawings of Angkor Wat and Cambodian weavers from his 1956 trip to Southeast Asia – his first outside the US – with an unrequited crush, Charles Lisanby. New, too, are the delightful drawings of naked feet, arranged balletically amongst vases of flowers, he made in the early 1960s, as though staging his more famous I. Miller shoe ads. Campy portraits of friends in drag – their wigs stacked with flowers and fruit, à la Carmen Miranda, or necks decorated with pearls – are evidence that Warhol enjoyed a vibrant queer life in the late 1950s and early ’60s, despite being publicly in the closet. ‘Whew something happened I’ll never forget’, Warhol has inked above a pair of male profiles that come almost close enough to kiss. He wryly adds: ‘Wait just a minute I’ll think of it yet’…

Main image: Diana Davies, Untitled (Marsha P. Johnson Hands Out Flyers For Support of Gay Students at N.Y.U.), c.1970, digital print, 27.9 × 35.5 cm. © The New York Public Library/Art Resource, New York; photograph: Diana Davies