Shows to See in the US This August

From Alix Vernet’s street casts at Helena Anrather, New York, to Myrlande Constant’s mystical tapestries at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles

From Alix Vernet’s street casts at Helena Anrather, New York, to Myrlande Constant’s mystical tapestries at Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles

Alix Vernet

Helena Anrather

7 July – 11 August

Through the second-storey window of Helena Anrather gallery, Alix Vernet’s exhibition ‘Street Casts’ looms over this bricolage. Vernet’s art draws on the city’s rich architectural vocabulary, as in a series of stoneware sculptures cast from mouldings that have survived the urban renewal, which the artist recombines as friezes. Three works reproduce lintels from decorated tenements – mass housing that immigrant architects personalized with ornamentation, granting the working-class buildings a sense of dignity, resiliency and charm – on Saint Marks Place. The artist befriended the buildings’ tenants before mounting their fire escapes to capture the embellishment in latex. Beneath each lintel is a brief poem that doubles as a title: ‘ERECTED / ALSO / AS A / SHADOW / SHE / WOULD / CURSE’, for instance, or ‘BEGIN HERE / CLOSE / TO HOME / SO CLOSE / THEY / CANNOT / BE SEEN’ (all works 2023). Written in letters cast from memorials around the city, the poems read as eulogies for a New York that more proudly wore its history. Glazed in an opaque quicksilver, the sculptures gleam dully like distorting mirrors, as if haunted by a melancholy nostalgia. – Will Fenstermaker

Erika Verzutti

Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College

24 June – 15 October

The more than 60 sculptures in ‘New Moons’, Verzutti’s current exhibition at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, emphasize the ways in which the cross-pollination of references and modes of making can scramble logic and complicate meaning. Wax looks like brie cheese in the wall relief Gober (2016), while the lumpy Turtle (2015) more closely resembles a modernist coffee table than the eponymous reptile. In the newly commissioned wall work Crisis of Sculpture (2023), veiny limbs ending in brass moons sit on a gouged celestial surface that you desperately want to stick your fingers into. Constant play with materials both ‘high’ (bronze, wood, porcelain) and ‘low’ (clay, Styrofoam, papier-mâché) underlines the performativity of Verzutti’s objects: heavily tactile bodies evoking plants, animals, cosmic formations or a slightly confusing combination thereof. – Mariana Fernández

Myrlande Constant

Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles

26 March – 27 August

Thirty years ago, when Haitian artist Myrlande Constant quit the foreign-owned wedding dress factory where she’d worked with her mother as a teen, the Vodou practice of drapo (flag-making) was still utilitarian and male dominated. Constant’s mother taught her how to sew; the factory honed her technical hand and aesthetic eye. Soon after, Constant acquired an airy studio atop Port-au-Prince, surrendered to the spirits and began working her magic with fabric, sequins and beads.

‘The Work of Radiance’ at the Fowler Museum at UCLA encapsulates, celebrates and hints at the further potential of Constant’s innovations like a lone sequin throws multi-directional light. The first institutional survey of a contemporary Haitian woman artist in America, the show blooms across five thematic sections: a shimmering extravaganza fit for Constant’s conceptually mystical and formally theatrical approach. – Vittoria Benzine

Pacita Abad

Walker Art Center

15 April – 3 September

I had to resist the urge, walking through Pacita Abad’s retrospective at Walker Art Center, to wrap myself in one of the artist’s colourful, hand-embroidered, canvas and fabric trapunto works. I wanted to be engulfed in their puffy, shimmering surfaces – at once maps, bodies and repositories. Foothill Cabin (1977), one of Abad’s earliest paintings, seems to echo this sentiment: the central figure – the artist’s husband – lies in bed, almost subsumed by an enormous patchwork quilt. Hovering above him are a series of yellow squares depicting lively figures inspired by Indigenous American art, while a swath of phulkari (Punjabi embroidery) stretches across the canvas like a textile sky.

Born in the Philippines in 1946, Abad lived a politically inflected life: photographs in the exhibition catalogue depict her participating in student protests in Manila during the 1960s and San Francisco’s countercultural movement of the 1970s. The central galleries house a broad selection of her social-realist paintings, including the four-and-a-half metre ‘portable mural’ Flight to Freedom (1980), whose matter-of-fact depiction of Cambodian refugees verges on National Geographic photojournalism. Though admirable, these works left me with the sense that the most interesting aspects of the artist’s interaction had occurred off canvas. – Simon Wu

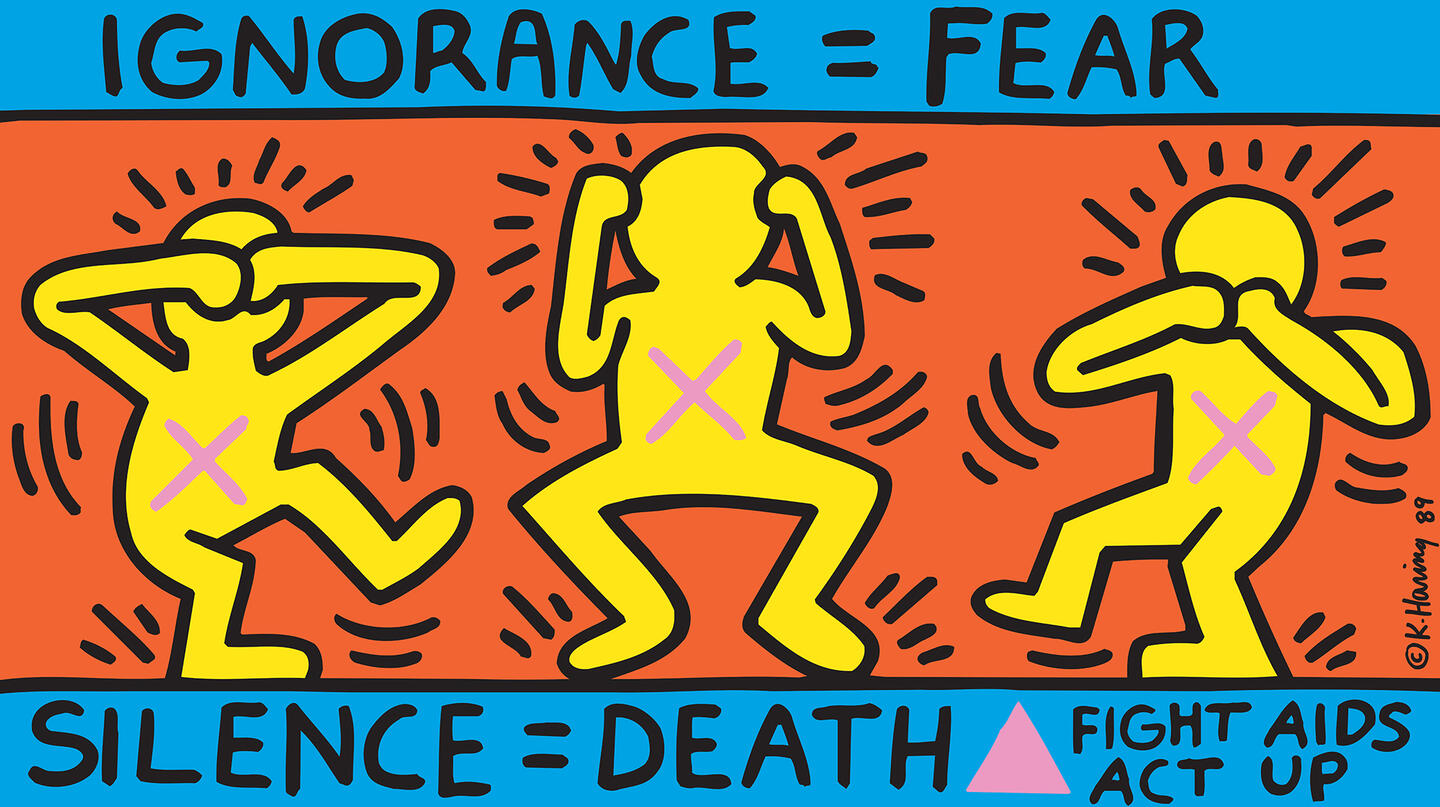

Keith Haring

The Broad, Los Angeles

26 March – 8 October

I predict few will linger long enough to absorb the four paragraphs of potted biography on the neon yellow wall welcoming visitors to ‘Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody’, before surging onward into the first gallery, which is painted with fluorescent pink and orange stripes. The green and orange Statue of Liberty (1982) commands the room, graffitied to high heaven by Haring and his then-15-year-old collaborator, LA II (Angel Ortiz). Nearby is a Corinthian column, similarly improved, while on the walls hang Haring’s Day-Glo paintings on muslin, aluminium and Formica.

So it begins. ‘Art Is for Everybody’, the first museum exhibition in Los Angeles of Haring’s work, is a deep dive that takes us from this part re-creation of the black-lit basement in Haring’s breakout 1982 show at Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, through to his (intentionally) Unfinished Painting (1989), done months before his death from AIDS-related illnesses. The entire span of the show – which includes early works on paper from 1978, when Haring was just 20 – is just 11 short years; the enormity and impact of Haring’s output is awesome. Despite the relative consistency of his style and subject matter, it is also – perhaps surprisingly – never boring. – Jonathan Griffin

Main image: Pacita Abad, Old Dhaka,1978, oil on canvas. Courtesy: Pacita Abad Art Estate; photograph: Rik Sferra