A Story of Love and Hate: Netflix’s Wild Wild Country

This new docu-series on a cult established in Oregon in the 1980s is a timely exercise in tolerance and a fascinating insight into extremism

This new docu-series on a cult established in Oregon in the 1980s is a timely exercise in tolerance and a fascinating insight into extremism

Once again, we’re infatuated with cults, nearly half a century since the headline groups of the late 1960s and ’70s – The Family International, The Manson Family, Heaven’s Gate and Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple – gave the term the weight of an inevitable, dirty mistake. Now it seems that we’ve reached peak nostalgia for that era, where the horrors perpetrated by the above have passed into history books and we can pretend their actions are that of another society. Just like fashion and music, vintage beliefs eventually become charming.

The last few years have seen an uptick of cult-focused media: podcasts such as Cults (2017–ongoing), You Must Remember Manson (2017–ongoing), a best-selling novel (Emma Cline’s 2016 The Girls) and a spate of television shows on the subject, including Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (2015–ongoing), Waco (2018) and now, Netflix’s Wild Wild Country (2018), a six part documentary miniseries about the Rajneesh movement and their brief but controversial residency in America in the 1980s.

Compared to other groups, the Rajneeshees, named after their founder, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, or ‘Osho’, have been a footnote of cult history. This is surprising, considering that its 7,000 followers (sannyasins) – best known for dressing exclusively in orange, pink, red and maroon uniforms – erected a fully functional, incorporated city on farmland in rural Oregon, the Rajneeshpuram; committed one of the largest bio-terror attacks in American history (infecting 751 people with salmonella in an attempt to curb voter turnout in a local election and aid their own candidate) and plotted to assassinate a US Attorney. Most likely, this story lingered in the shadows of cult history because of the Peoples Temple’s 907-person mass suicide via poisoned Kool Aid in 1978, which occurred only a few years before the events in Oregon. (Interestingly, the daughter of Representative Leo Ryan, who the Peoples Temple assassinated shortly before their mass suicide in Guyana, was a Rajneeshee.) Enter Netflix.

Told using a combination of new and vintage footage of both ex-Rajneeshee and conservative Oregonians, by brother-directors Chapman and Maclain Way, Wild Wild Country is masterful at manipulating its audiences’ alliances, never settling into a fixed perspective on the situation. In the beginning, the Rajneeshees seemed headed toward utopia. Sure, they were naive and isolationist, but their project was a distinctly American one: find a plot of land and make your own world. It seems hard to fault them for this mission, with its core appeal to the ‘American dream’, and yet, this is exactly what the citizens of the local town of Antelope, 18 miles away, do.

This tiny town of less than 60 conservative retirees are disgusted by the social experiment occurring up the road from them. They are unapologetically xenophobic and remain difficult to sympathize with. When they conclude that the Rajneeshee pose a threat to their way of life, they greet them with guns. In reaction, the Rajneeshee arm themselves ten-fold, introduce gun-wielding patrols and eventually turn to real estate thuggery and direct violence in order to occupy Antelope. As they see it, they are victims in a long lineage of religious persecution, and brute force is their only course of action. The viewing experience is a relevant, timely exercise in tolerance, and a fascinating treatment of the most extreme relationships that arise in the great American diversity experiment.

Usually, the coverage given to cults succeeds at depicting controversy and fails to convey that most fundamental phenomenon constitutive of any sect: a deep faith in the leader. I have to assume that all these figures had some kind of charisma – Manson’s gaze, Osho’s ‘presence’ – but it’s a difficult quality to capture on film. The result often leaves the viewer alienated and unable to sympathize with either the followers or the leader, transforming a cult’s devotion into a ‘McGuffin’, a meaningless plot engine.

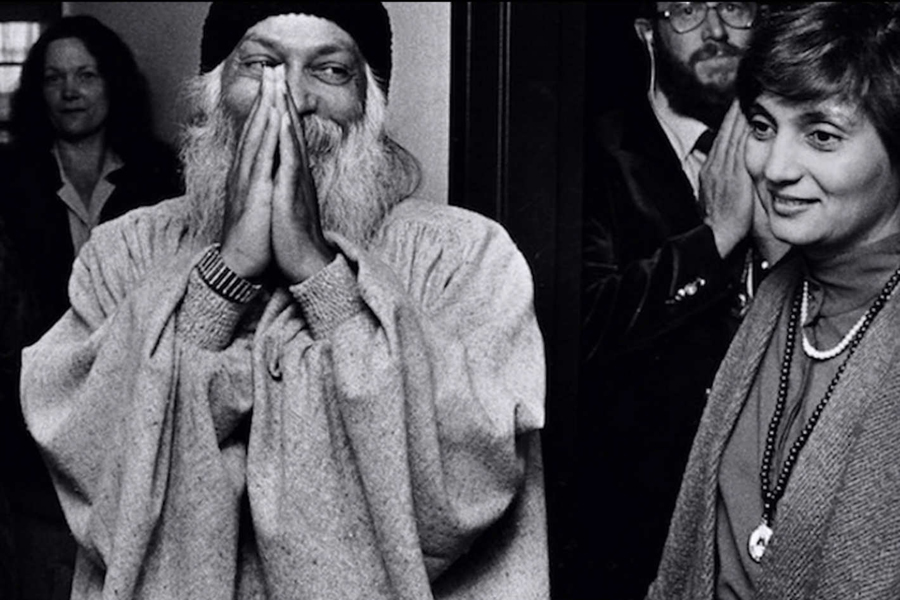

For most of Wild Wild Country, Osho is a worthy blank slate. After years of charismatic public speaking in India, he takes a vow of silence, and so does the film toward him, offering little about his motivations and principles. He is a passive figure while his ‘disciples’, particularly those in the leadership committee led by his secretary, Ma Anand Sheela, become increasingly proactive in steering the direction of their intentional community. (In fact, this is what ultimately saves him from punitive legal action.) The most we come to know about Osho is that he rejects marriage, fetishizes shiny things (most famously the Rolls-Royce he used for his daily ‘drive-bys’ through Rajneeshpuram) and holds his hands in prayer position any time a camera is aimed in his direction. But through silence he gains gravitas, and enough mystery to allow for the possibility of his enlightenment. Later, when he does speak after Sheela’s sudden departure following a murder attempt on Osho’s doctor, this possibility deflates – he is full of spite, malice and sexism for his former secretary; he denounces her to the world by calling her names and suggesting that she operated without his consent. Beyond that, nothing he says has the slightest whiff of wisdom. For me, this was the moment, the film turned on its subject.

Retrospectively, however, all the actions of the Rajneeshee dissolve into a cautionary tale. To further emphasize this, the series includes a few clips from the German documentary, Ashram in Poona, secretly shot by Wolfgang Dobrowolny in 1978 on the sannyasins in India. The film depicts a bearded Rajneeshee (not Osho) presiding over a group of pretty, young, fully-nude acolytes, encouraging them to attack and scream at each other in tongues. It’s shocking, and when the film was screened in Oregon during the height of Rajneeshpuram, it fuelled local paranoia. Watching the video now, the exhortations look like an extreme version of the cathartic protests happening all across the world at the time. But perhaps the effect of the video is somewhat muted in our current moment when extreme exercise routines and vomit-inducing ayahuasca ceremonies are in fashion, and yoga studios and retreats (many with their own questionable leaders and alt-Hindu ideologies) are within a stone’s throw of every quaint American town.

Main image: Chapman and Maclain Way, Wild Wild Country, 2018, film still. Courtesy: Netflix