Strike a Pose

The consistently inconsistent career of Scottish artist Bruce McLean

The consistently inconsistent career of Scottish artist Bruce McLean

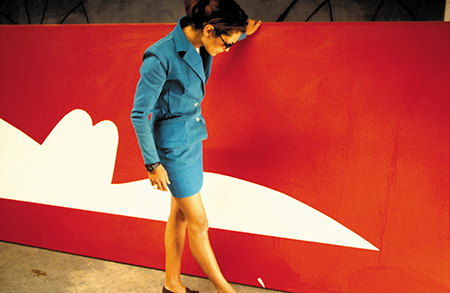

Bruce McLean has spent half a century trying to attain the perfect pose. He frequently stars in his own photographs, videos and paintings, lounging on plinths or dressed in snappy suits – as if to suggest that the artist is an unbearable egotist, a poseur. McLean – who in person is affable, easy-going and self-critical – parodies social preening through hyperbolic posturing, yet also makes it look supremely cool and effortless. I can think of few works that explore this dynamic as effectively as Urban Turban (1997), a three-screen video work with a stentorian soundtrack by Dave Stewart (of the band Eurythmics). Recently exhibited as part of McLean’s retrospective at Firstsite in Colchester, Urban Turban re-imagines the art world as a parade of inane stances and outlandish headwear.

Although Urban Turban lacks anything as obvious as narrative, McLean’s film is nominally about an artist who gives it all up to become a banker; a reversal of the plot of Tony Hancock’s feature film The Rebel (1961). We witness a series of tightly edited vignettes: three men in assorted national headgear (sombrero, fedora, fez) admire a grey-toned painting by McLean of roundels of brie (The Cheese Players, 1983); a sharply turned out curator pouts beneath a towering piece of millinery resembling an inverted Wellington boot; McLean, dressed in a mac and a bowler hat, enters and exits the glass doorway to the former Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London (which represented him at the time). Superimposed over these images at random intervals are capitalized, nonsensical pronouncements such as ‘CURATOR DISCUSSES BRONZE BOWLER ACROSS STATUES' and 'INTERNATIONAL CURATOR IN SAUSAGE FOR STETSON SWITCH'.

Urban Turban reprises motifs from several protean decades of artistic production: the anarchic formlessness of McLean’s early Post-minimal, Conceptual and Land art pieces of the 1960s; the social satire of his performance work in the 1970s (notably with the ‘pose band’ Nice Style); and his improbable success in the steroidal Neo-Expressionist painting scene of the 1980s. (He is a colourist with a punchy graphic sensibility.) McLean appeared in canonical exhibitions of the late 1960s and ’80s (‘Op Losse Schroeven’ at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, and ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ at Kunsthalle Bern in 1969; ‘A New Spirit in Painting’ at the Royal Academy, London, in 1981; ‘Zeitgeist’ at Martin-Gropius-Bau, in Berlin, 1982), and had his first solo show at Konrad Fischer’s influential gallery in Dusseldorf in 1969. He is one of the major figures to have emerged from the sculpture department of St Martin’s School of Art in London, and his peers include Jan Dibbets, Barry Flanagan, Hamish Fulton, Gilbert & George, John Hilliard and Richard Long. For better or worse, his anti-establishment humour also had a huge influence on the generation of artists to emerge in the UK in the 1990s.

The anxiety of influence has long been a point of critical engagement for McLean, never more so than in relation to his peers in the us. He first encountered us Minimalism and Conceptualism in the 1960s, and reacted to the absurd machismo and seriousness of the photographs of Robert Morris and Walter De Maria published in the catalogue for ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ with two 16mm film works – In the Shadow of Your Smile, Bob (1970) and A Million Smiles for One of Your Miles, Walter (1971). The first features McLean discussing his intentions as a sculptor; the second shows McLean lying face-forward on the white lines of a football pitch, as if knocked-out by Mother Earth. While these videos have conventionally been understood as poking fun at their protagonists, I see them as backhanded homages. Both reveal a sense of uncertainty and self-questioning – of working ‘in the shadow’ of Morris and De Maria. McLean also made another film about a peer whose reputation was solidified early on in the US: The Elusive Sculptor Richard Long (1970) follows an interviewer strolling through a park in London asking passers-by if they have seen the famous ‘walking artist’. Unfortunately, this work has been lost, although McLean tells me he still hopes to find it in some dusty corner of his attic.

McLean’s humour is aligned with a particular anti-establishment way of looking at the world typified by British comedians of the 1950s and ’60s, including Tony Hancock, Peter Sellers and Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Their comedy was carried by the groundswell of the 1960s counterculture, and founded on an almost Oedipal impulse to reject or undermine figures of authority. McLean was not the only subversive to emerge from St Martin’s. Gilbert & George’s early performances explored national and artistic identity through parody and camp (McLean collaborated with the duo in the performance Interview Sculpture, 1969). In 1966, John Latham undertook his infamous Still and Chew action with students from St Martin’s, in which a copy of Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture (1961) was masticated, spat out and left to ferment before being returned to the school’s library in a vial. (Latham’s teaching contract was not renewed.)

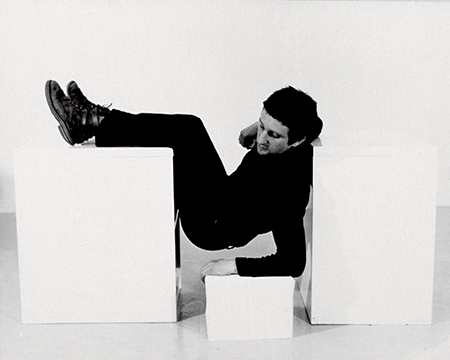

A number of McLean’s early works subvert the high-minded self-image of the ‘New Generation’ sculptors who taught at St Martin’s (including David Annesley, Philip King and Isaac Witkin) and who prided themselves on the not-so-spectacular feat of freeing sculpture from the plinth, allowing their works to sit directly on the floor. In his exhibition at Situation Gallery in London in 1971, McLean presented a series of plinths on which were exhibited images ripped from magazines of desirable consumer products (a hair dryer, shoe tree, food mixer, etc). He subsequently had a series of photographs taken of himself balancing awkwardly on the same plinths (Pose Piece for Three Plinths Work, 1971), as if to suggest comical versions of Henry Moore’s figures. In retrospect, this would be a defining move into a deep exploration of the pose – replacing his early formless found materials with his own body.

The apotheosis of McLean’s laconic interest in art-as-posture is the performance group Nice Style1, ‘The World’s First Pose Band’, formed in 1971 at Maidstone College of Art with members including Ron Carr, Gary Chitty, Robin Fletcher and Paul Richards. Lasting until 1974, Nice Style was a ‘band’ only in the loosest sense – they had the postures and the costumes but played no music. Their first ‘gig’ was as an opening act for The Kinks at Maidstone College of Art on 26 May 1971. Early pictures of the group show them in dazzlingly naff Glam Rock outfits, but they quickly began to examine other variations of the pose, wearing formal dinner suits and bowties alluding to aspects of social climbing in Britain’s class-rotten society. Their acts drew from the semaphore of Renaissance art, in which the acute angles of limbs, chins and brows indicated faith, power or subservience. The band’s later performances confronted anxieties about domestic status embodied in House and Garden magazine’s obsessive depiction of well-arranged pot plants and adverts for freezers and irons – what Mel Gooding has called ‘problems of preparing the home as the setting for the perfect pose’.2 Deep Freeze (1973) featured the troupe on stage at the Hanover Grand dressed in white tuxedos, opening and shutting a series of chest-shaped freezers in orchestrated actions. Nice Style’s defining performance was also one of their last. High up on a Baroque Palazzo (1974) featured the group performing synchronized actions ‘training’ to get the ‘perfect pose’ – climbing ladders and ropes, repeatedly opening and shutting doors on the purpose-built set in response to commands shouted from off-stage.

Underpinning McLean’s work is an ethics and politics that is both pressing and hard to define. Gooding has noted that McLean is part of a ‘guerrilla campaign’ in the ‘art war’, defined somewhat broadly as ‘the use of art for illegitimate purposes of personal and national promotion’.3 (In terms of the latter, note the appearance of trilby hats in drawings and paintings from the early 1980s, such as 1982’s Going for God; these are a reference to Joseph Beuys, whose cultish reception in Germany McLean found particularly unsavoury.) While the precise battle lines of this ‘war’ are often unclear, it is evident that McLean’s works use humour in order to prompt the viewer to be more keenly aware of the darker machinations of contemporary art. He has done this by making works that undermine art as being immutable or mystical, and at a structural level by frequently working outside of the gallery system. Nice Style performed largely in theatres and art colleges, and McLean has more recently collaborated with architects such as Will Alsop and David Chipperfield and, following an invitation from a businessman working to develop the site of Fulham Pottery in London, produced a series of bold and colourful ceramics.

McLean grew up in Glasgow, with a father and grandfather who both had a penchant for the dramatic and surreal. His grandfather, for example, liked to set the budding young artist the task of drawing either ‘a potato against a black background, or a scone off a plate’. Consequently, one of McLean’s favoured motifs is the potato, the subject of his recent painting, A Carefully Peeled Golden Wonder against a Dark Background (2014). As a child, McLean would go on holiday to the Isle of Arran, off the west coast of Scotland. He returned to the island in 1969 to make a series of works using huge rolls of paper that wryly addressed both painting en plein-air and contemporary Land art (Seaskapes, Shoreskapes, Rockskapes, Treescapes, and Watercolour Under Water). Each piece was a futile attempt to capture the ineffable – for example, by draping craggy seaside rocks with paper sheets and trying to reproduce hues of the covered rock in watercolour. It is also significant that, since 1965, McLean has lived in Barnes – a leafy, unfashionable corner of south west London. Most of his early works were made in or around the area, lending them a quiet, eccentric air that is markedly different to the heroism of the Land artists who ventured into deserts and mountains to make their work.

For all McLean’s freewheeling energy and desire to be inconsistent, his work has shown a remarkable continuity in its engagement with the practice and history of sculpture. While he has always painted on paper or canvas, he repeatedly claims that he is ‘not a painter’, and even his performance works are sculptural in their intricate, well-built set design. One of his more recent paintings, The generation game of sculpture, cuddly toy, a … no I’ve said that (2010) references both this weighty inheritance and a long-running British TV show (The Generation Game, 1971–2007) in which contestants had to memorize consumer goods placed on a moving conveyor belt to win them as prizes. The painting features a parade of sculptures, arranged much like the objects in the TV contest – a Constantin Brânçusi, a figurative work (possibly a Moore) and an abstract piece (possibly by Anthony Caro). Other paintings address major sculptors of the 20th century in familial terms – Tony and Barry (2010) features outlines of works by Caro and Barry Flanagan; Two Henrys, two Barrys, a Constantin and a Chair (2012) nods again to Flanagan as well as to Moore and Brânçusi.

Moments before the opening of his recent retrospective at Firstsite, Colchester, McLean told me that he has plans to make a new body of sculptural work. He won’t expand on exactly what form this will take, but promises it won’t look like ‘anything you’ve seen before’. I am unsure whether he’s telling me that it won’t look like sculpture at all (which would hardly be surprising), or whether he is on the cusp of a full-scale return to a form of material practice he’s spent half a century dodging. Perhaps that would be the ultimate gesture in a lifetime of seeking the definitive pose.

1 McLean tells me that the name is derived from the slogan ‘British Airways: The World’s Favourite Airline’; Paul Richards claims that the name is from Ron Carr who ‘used to walk around saying he was from Castleford in Yorkshire and that he would always say “nice style” – as in, “That’s got nice style.”’

2 Mel Gooding, Bruce McLean, Phaidon, London, 1990, p. 67 3 ibid., p. 121

Bruce McLean is an artist based in London, UK. His solo exhibitions in 2014 have included: 'Another Condition of Sculpture', Leeds Art Gallery, UK, and 'Action Sculpture Potato Painting', Bernard Jacobsen Gallery, London. The major retrospective 'Bruce McLean: Sculpture, Paintin, Photography, Film', runs at Firstsite, Colchester, UK, until 30 November and is accompanied by a monograph edited by Michelle Cotton. On 15 October, Brucle McLean will give a performance/lecture at Frieze London as part of Frieze Talks.