Studio Ghibli’s ‘Grave of the Fireflies’: A Devastating and Timeless Tale of the Second World War

Isao Takahata’s landmark 1988 anime, which now receives its US theatrical release, crafts a dark moral universe through moments of poignant stillness

Isao Takahata’s landmark 1988 anime, which now receives its US theatrical release, crafts a dark moral universe through moments of poignant stillness

While the dates of wars are fixed by declarations and cessations, the boundaries of conflicts are much more porous for those involved. Terrible ripples occur before and after. The Rape of Nanjing took place four years before the Pacific Theatre of the Second World War began. Jewish civilians were murdered in a pogrom in Kielce by fellow Poles in 1946, having only recently survived the Holocaust. The brutality and trauma of war long outlive the armistice. They are there as mines in the earth and the sea, toxins in the rubble and air, wounds in bodies and grief in hearts. History neatly brackets each conflict and moves on, even when people struggle to.

Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), which is only now receiving its US theatrical release, refuses to take such an approach. Beginning with a dying figure in Kobe’s Sannomiya Station, in the aftermath of Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, it is a film innately and brutally wed to that conflict. It was adapted from a 1967 short story, of the same name, by the writer Akiyuki Nosaka. This tale was based on Nosaka’s own bitterly-regretful adolescent experiences when, after Kobe had been firebombed by the US airforce, he had tried and failed to keep his younger sister alive. Both the stark realism and elegiac quality were brought to vivid life in the anime version directed by Takahata and his animators at Studio Ghibli.

Takahata’s own eerily-similar childhood experiences during wartime bombing raids fed into the film. One night, in the summer of 1945, 100,000 incendiary bombs were dropped on the Japanese city of Okayama. The 9-year-old Takahata had run outside with his sister, in their nightclothes, and became separated from their mother in the panic of the crowd as the city burned around them. His sister was injured in an explosion, but he struggled on with her until they reached the relative safety of a river. Half the city was destroyed and over 1700 people died during that night, including those who took refuge in the air raid shelter near Takahata’s now-incinerated home. These were scenes from memory translated into the Grave of the Fireflies, and the fates of the film’s young brother and sister protagonists, Seita and Setsuko.

The emotional weight of Grave of the Fireflies owes much to Takahata’s mastery of place and character. Even the most jaded viewer, immune both to sentimental schmaltz and posturing brutality in cinema, finds their resistance slipping away as they watch. Many cite it as one of the most beautiful and devastating films they’ve seen, and it has become something of a cliché to say it’s a film you cherish and never want to see a second time because of its impact. There are scenes of horror from the apocalyptic wreckage of an obliterated city to the sight of a loved one burned and bloodied, being fed on by flies. For what is ostensibly a children’s film, it pulls no punches.

Yet the real devastation comes from how entrancing the film is. The small details are crucial in this. In recurring shots of a tin can of Sakuma fruit drops carried by Seita and Setsuko, the film finds a symbol of hope and lost normality in a world falling apart. A sense of stillness occurs again and again (Takahata’s own particular take on the Japanese concept of mono no aware), especially in the midst of horror – a silent alleyway surrounded by an inferno, a leaf floating in a water tank. Takahata’s framing and pacing are immaculate. Tram windows accelerate by. Bomber planes pass over cityscapes. Yet we come back continually to tiny fleeting child-sized sanctuaries of calm, all the more precious because of their transience. For anyone with a young child, the movement, curiosity, charm and vulnerability of the little sister Setsuko (voiced by Ayano Shiraishi) is rendered with almost-unbearably poignant accuracy. For any young person who has ever struggled to know what to do or how to live in perilous circumstances, Seita (voiced by Tsutomu Tatsumi) likewise resonates.

Takahata long denied that Grave of the Fireflies was an anti-war film (though it self-evidently is) partly to prevent it being pigeonholed as a worthy moralistic tale. It is far more than that. It is a work of art and history that resists simple interpretation and encourages multiple perspectives. It is a story about the perils of childhood in an adult world, with war being, among other things, a profound betrayal of children. It is about the incomprehension that comes when the human is confronted with disaster on an inhuman scale; an entire city turned into smoke on the horizon. It is about how dangerous succumbing to inertia or living in delusion can be, how casual and self-justifying adult cruelty can be, and what happens when society turns away from the vulnerable. It shows us how easy it is to become abandoned: not just the callous aunt or the jaded passers-by who turn away from the pair, but in terms of becoming lost in the simultaneity of life. There are always other untold stories going on in the backdrop of Takahata’s film.

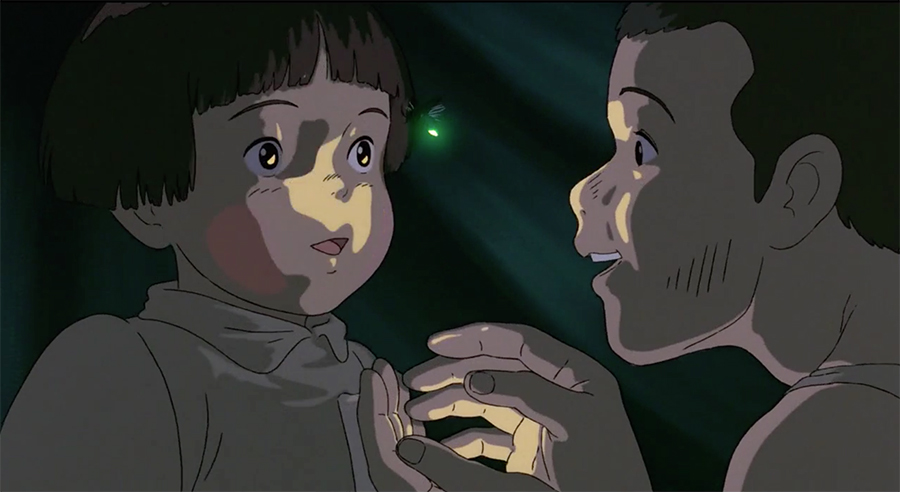

The film tells these stories, not through lectures, but by images of indifference and pathos; the workers at the beginning, for instance, sweeping up junk and bodies alike. It balances these with kindness, empathy and a small but ecstatic sense of awe – a boy trying to distract his distraught sister by swinging on horizontal bars, a girl offering her brother the meaningful and meaningless contents of a child’s purse, the brief incandescent lives of fireflies that illuminate briefly what is hidden in the dark.

Grave of the Fireflies is devastating because it suggests that the moral universe may not bend towards justice as we reassure ourselves, but that the good and innocent die regardless and even their fates are disregarded. Like any truly honest tale of beauty, it is discomforting. It asks something of us, which is why many do not return for a second viewing. It is a tale then not just of the Second World War and its aftermath but our times and those to come.

Main image: Isao Takahata, Grave of the Fireflies, 1988, film still. Courtesy: Studio Ghibli, Studio Canal