Thomas Schütte

Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany

Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany

‘Speak as if you were speaking to yourself. MONOLOGUE NOT DIALOGUE’, Robert Bresson instructed his actors in his seminal 1975 book Notes on the Cinematographer. The French auteur’s directive is applicable when considering the ‘models’ of Thomas Schütte, whose sculptural figures, theatrical mock-ups and architectural prototypes flaunt an opacity that seems to delimit a similarly self-generating conversation. From the cheery startle of Schütte’s series of metallic monster-like figures, ‘Große Geister’ (Big Spirits, 1995–2004), to the Modernist architectural models of ‘Ferienhäuser für Terroristen’ (Holiday Homes for Terrorists, 2002), the German artist has long pursued a multivalent practice that – though it grew out of the Minimalism and Conceptualism of early 1970s Dusseldorf, where Schütte studied under Gerhard Richter and Benjamin Buchloh – has spoken mostly to itself. That conversation, broaching biggies like power, modernity and monument-making, carries forth with an internal humour that the viewer readily identifies but cannot entirely understand. Obscure or not, it’s this humour – dry, dark, a bit jumpy – that ties together Schütte’s wide-ranging oeuvre, as was testified to by the Haus der Kunst’s survey of some 100 of his works from the past three decades. If the ensuing ‘monologue’ didn’t quite kill, it did do what the best comedy does, imparting flashes of cognition of the acerbic beauty found in the human condition.

Schütte’s ‘Große Geister’ series stalked the entrance to the show, foreshadowing the exhibition’s partial focus on the figure and the artist’s ambivalent relationship to it. Melty, molten and reflective, these aluminium figures evince both menace and levity: part Darth Vader, part Pillsbury Doughboy. Outsized, they put the viewer at a disadvantage, an auspicious start to Schütte’s lecture on power relations. The central hall was impressively appointed with more of his subversions of the figure-as-monument. Großer Respekt (Large Respect, 1993–4) and Kleiner Respekt (Small Respect, 1994) feature a daringly depressing kind of mock war memorial: a trio of hobos tied together, back to back, in a circle. Hung near the ceiling, Schütte’s ‘Innocenti’ (1994) portraits gazed down on them. Evoking both Francis Bacon’s tortuous facial blurring and recent imagery of face-transplant patients, the luminescent black and white photographs seemed to follow one’s movements across the gallery, leading to the show’s centrepiece: a nearly six-metre-high plaster model of Mann im Matsch (Man in Mud, 2009), a bronze sculpture recently installed in the artist’s hometown of Oldenburg, Germany.

In the early 1980s Schütte began a series of small sculptural works depicting men stuck in mud. The metaphor was obvious: the hero rendered helpless and immobile. Gradually the works became larger. In this new model, the figure has the quality of a Socialist Realist everyman. As an anti-monument, the work could not be better situated than in the museum Adolf Hitler built to glorify the Third Reich with exhibitions of ‘great’ German art. But despite this set-up, the work fails in its very effort to ‘fail’. Its meaning is at once too obvious, its necessity too opaque, the joke too familiar. Far more effective was a work found in one of the side galleries, 14 Skizzen zum Projekt Großes Theater (14 Sketches for Large Theatre, 1980), which comprises a series of photographs of theatrical models featuring Princess Leia action figures striking various poses in front of banner-like fragments: ‘Freedom’; ‘In the Name of the People’; ‘Pro Status Quo’. The vague pronouncements evoke the contaminated doublespeak of corrupt regimes (National Socialist and Democratic). What the towering Mann im Matsch is unable to achieve – its critique cancelled out by its own grandiosity – this early work did effortlessly.

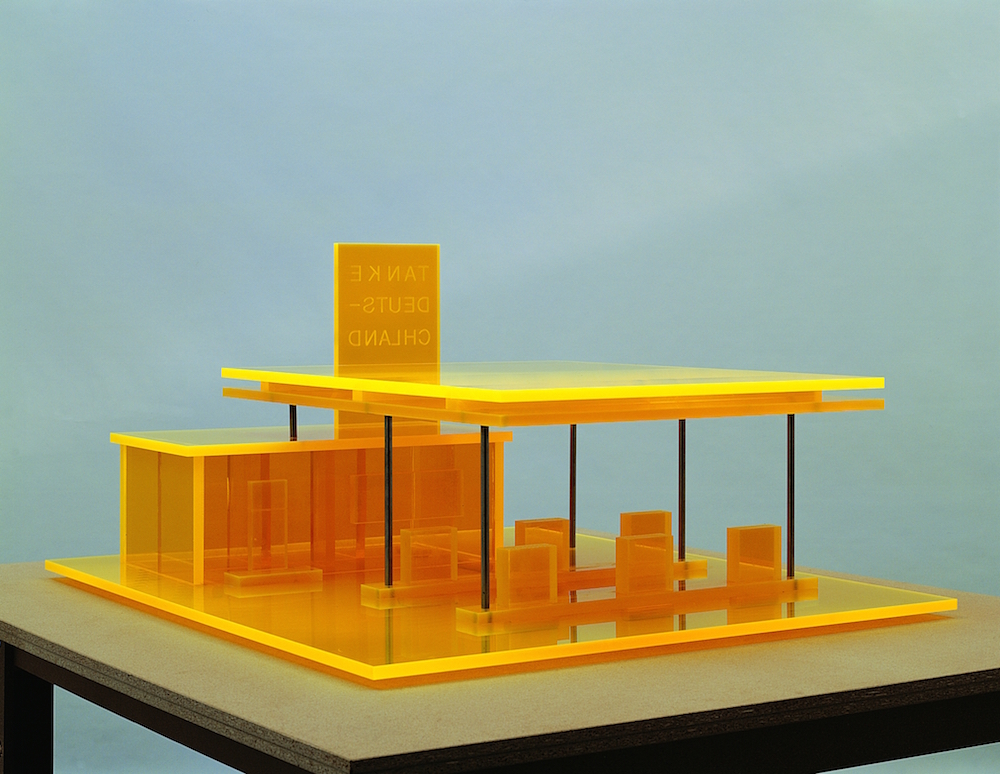

The surrounding galleries attested to Schütte’s range – tapestries, drawings, architectural models and sculptures abounded – and his reprisal of familiar forms: the Modernist female nude, the floral watercolour, the figurative bust. ‘Frauen’ (Women, 1998–2006), a sculptural series of large, reclining women, are a pastiche of sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso, with their lumpy, sensual curves rolling above rusty steel tables (though one of the robust thighs features a handle for easy lifting). Deprinotes (2006–8), Schütte’s watercolours of flowers and figures, are expert but the statements written across them, such as ‘I GOT WORMS’, can fall flat. The ‘Kreuzzug Modelle’ series (Crusade Models, 2002–6) features architectural models made in the wake of 9/11; despite the sensational title, the works are austerely beautiful and give little away. More generous, and at the same time more mysterious, is a new series on view for the first time: ‘Klotzköpfe’ (Blockheads, 2008), 12 small, ceramic, squished heads given a golden glaze. Their blurred features (achieved after the artist drops them on a table) and slight stature deftly play off the shimmer of their surface. Abused and then dusted in gold, this process seems to mirror their maker’s famous ambivalence, be it about icons, art-making, justice or beauty. The diminutive, glittering models – formed from Schütte’s wellspring of bright doubt and blackest humour – dazzled.