Thought Maps

Gianfranco Baruchello’s long career encompasses painting, sculpture and film as well as farming and psychoanalysis

Gianfranco Baruchello’s long career encompasses painting, sculpture and film as well as farming and psychoanalysis

I would have to be as good as Gianfranco Baruchello is at creating miniature worlds to keep within my 2,500-word limit for this essay. In a career spanning more than 50 years, Baruchello has lived through numerous historical, political and cultural eras; engaged with sculpture, painting, drawing and amalgams of all three; produced experimental films, performances and happenings; undertaken essay-writing and artist’s books, economics and psychoanalysis, farming and politics. Indeed, he hasn’t merely ‘engaged’ with these numerous subjects: Baruchello has produced hundreds of paintings and objects, each of which is populated by hundreds of figures, images, words and phrases. Not content with these achievements, however, the artist also founded Artiflex in 1968, a company for the ‘merchandising of everything’, Agricola Cornelia S.p.A. (Cornelia Farming) in 1973 (which ran until 1981), dedicated to land cultivation and, in 1998, launched his own Baruchello Cultural Foundation. He has been friends with philosophers, writers and poets: Marcel Duchamp, for example, with whom he discussed his work and ideas, and Jean-François Lyotard, who dedicated a book to him. Many more have written about him: Dore Ashton, Nanni Balestrini, Italo Calvino, Umberto Eco, Alain Jouffroy, Edoardo Sanguineti and Tommaso Trini, amongst others. He has had solo exhibitions in well-known galleries and participated in numerous biennials and landmark group exhibitions.

Yet despite his prestigious CV, Baruchello’s work remained relatively unknown beyond the confines of a small circle of aficionados until fairly recently, when a new generation of curators and artists – including Maurizio Cattelan, Massimiliano Gioni, Jens Hoffmann and Hans-Ulrich Obrist – sparked a revival of interest in his work, which culminated in a retrospective curated by Achille Bonito Oliva at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome, in 2011–2, and the artist’s participation at last year’s documenta(13), as well as in the upcoming 55th Venice Biennale, both in the Italian Pavilion and the main exhibition curated by Massimiliano Gioni. Why, then, is Baruchello’s name missing from conventional art-historical accounts of the past few decades? And what has led to this recent resurgence of interest in him? The reasons that prevented the initial recognition of his work are, I feel, most likely the same ones that have paved the way for this current revival.

Before we can answer these questions, however, we need to consider the unique trajectory of Baruchello’s career. Born in Livorno, Italy, in 1924 to a lawyer father, the artist grew up under fascism. He studied law at university, but on graduating decided to found a bio-chemical research company, which he ran until 1959. Interested in both poetry and literature, Baruchello was a self-taught artist who, by the early 1960s, had turned his passion into a career. His early works, which date from the late 1950s, combine elements of Surrealism with found objects and materials typical of New Realism. By the beginning of the 1960s, however, Baruchello’s visual vocabulary drew on Pop’s new mythologies as well as on New Dada, from which he derived not only sarcasm and irony but also the use of white (as Piero Manzoni and Robert Rauschenberg had done before him). But his form of appropriation was critical and political rather than formal: in some works from 1962, he covered his assemblages of objects, books and newspapers in Vinavil (a white, milky glue) to transform them into graveyards of memories, memorials to culture and information.

What differentiates Baruchello from Manzoni or Rauschenberg, however, is that for him the use of white is not an anti-narrative, Modernist end in itself, but a starting point to use the white plane again, to write and paint upon it – that is, to return from the negating gesture of pure white to a more affirmative, narrative idiom. In an early work on canvas, Primo alfabeto (First Alphabet, 1959–60), Baruchello depicts a series of symbols and ‘characters’ that create a visual language combining a cartoonist’s line with a primitive vernacular. In the years that followed, the artist transferred these and other ciphers onto paper – as in The Hypothalamic Brainstorm (1962), shown at dOCUMENTA(13) – wooden tables (from 1962) and aluminium (from 1966). For a brief period after 1964, Baruchello also applied his ‘characters’ to sheets of transparent Perspex that he stacked on top of one other to create an impression of physical depth.

The artist’s later works are vast expanses of monochrome canvas populated, through this process of miniaturization and fragmentation, by a multitude of objects, shapes and characters from history, politics and culture, often linked by a narrative. Many paintings are up to two metres wide; one measures eight metres and contains more than 3,000 images. Baruchello described these works as representing the process of thought,1 the space of the mind, the evocation of myriad correlations between the figures. One could say that each painting is a potential map of the brain or the visualization of a dream.

Aware of the impossibility of comprehending the infinite complexity of the information age that emerged during the 1950s and ’60s, Baruchello visualized a series of miniature universes. Seemingly exploded from an original nucleus of characters and stories, these innumerable fragments circulate in decentralized, non-hierarchical and non-Euclidian space. Mapping a new mental geography – which might be termed a ‘neuro-geography’ – Baruchello’s paintings raise questions about the hierarchies of history, politics and culture. In fact, despite their cartoonish appearance, they often speak of the political and historical tragedies of the time. In Jungkapital, Gesellenkapital, Maschinenkapital (Young Capital, Bachelor Capital, Machine Capital, 1975), for example, both politics and pornography have their part to play in an image depicting the workings of the capitalist economy. Likewise, Öyvind Fahlström employed Surrealist fantasy and a Pop aesthetic to address political topics ranging from the Vietnam War to anti-capitalist protests.

Those who have written about Baruchello’s work have often commented upon its narrative underpinnings. Trini, for instance, compared the artist’s creative process to ‘a fantastical journey that goes beyond the visual’ and observed how his subjects are endlessly mythologized.2 Personalities from history, the arts and current affairs are transformed into the protagonists of epic tales, where ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture are in constant flux, and where political and historical authority are continually being challenged. ‘This epic tale of the imagination is what counts,’3 Baruchello declared. History is fragmented and transformed in these works into myriad stories in which anachronistic events are fused to create an entirely new version of the past. Many years later, the philosopher Jacques Rancière wrote: ‘The real must be fictionalized in order to be thought.’4 He could so easily have been talking about Baruchello.

A seemingly boundless creative energy drove Baruchello to collate words and images almost without pause. Looking at one of his paintings is rather like reading Ezra Pound’s Pisan Cantos (1948) or T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland (1922), or listening to Bob Dylan’s ‘Desolation Row’ (1965), in the liner notes for which Dylan wrote: ‘I accept chaos. I am not sure whether it accepts me.’ Like the singer, Baruchello accepts the chaos of life and places it centre stage. In a painting such as Diego-Kid al servizio di sua maestà (Diego-Kid Serving his Majesty, 1974), for instance, the viewer finds Diego Velázquez’s 1656 masterpiece Las Meninas has been transformed into a commedia dell’arte containing a riot of details appropriated from the original painting. Viewers do not so much look at a Baruchello painting as travel through it, armed with infinite patience and, ideally, a large magnifying glass.

Duchamp observed that Baruchello’s works should be viewed ‘from close up over the course of an hour’.5 Baruchello’s paintings require the audience’s active participation, both physically and mentally: to read one of these works it is necessary to get close to it, to allow the eye to wander in different directions across the surface, seeking out details and connections. The artist challenges his viewers: seducing them, inviting them in, but ultimately frustrating their desire for uncomplicated stories. Constantly railing against story-telling and conventions of communication, Baruchello creates montaged worlds of fragmented associations.

The artist adopted a similar approach to the experimental films that he began to produce in 1963, the most famous of which is Verifica incerta (Disperse Exclamatory Phase, 1964–5). In collaboration with the filmmaker Alberto Grifi, Baruchello salvaged around 150,000 metres of celluloid that had been destined for destruction and spliced together clips from various Hollywood films to create a series of absurd and amusing shorts that undermine the conventions of traditional American cinema. Narrative linearity, the search for sentimental and dramatic effect, the celebration of heroism and other such myths of the spectacle become objects of derision in Baruchello’s work. Every so often, a cigar-smoking Duchamp makes a fleeting appearance: his calm demeanour ostensibly advising the viewer to slow the pace of unrelenting thoughts and observations, to introduce an intellectual pause into the rhetoric of cinematic artifice.

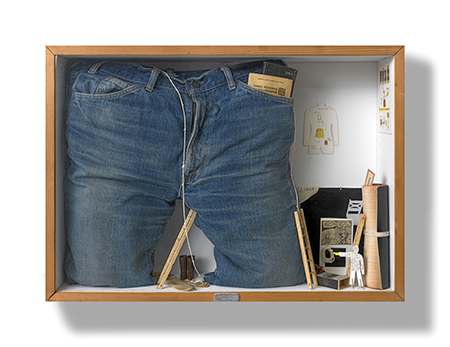

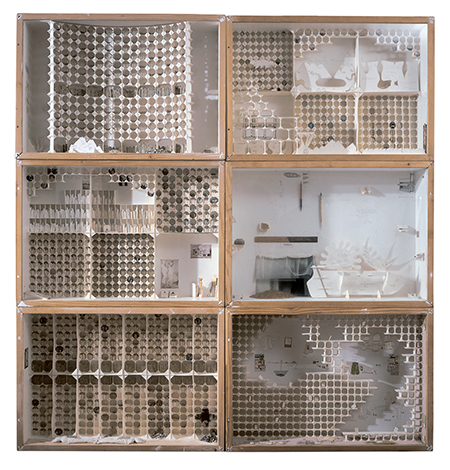

During the mid-1960s, and then again from 1973, Baruchello worked on a series of wooden cabinets in which he explored classification and archives. With a less fluid structure than the paintings, and revealing an almost obsessive approach to cut-out and collage, the cabinets centred on the accumulation and ordering of dates, images and stories to create theatrical or televisual mises-en-scène. While the cabinets constitute a different strand in Baruchello’s practice, they are still connected to the paintings, which he once described as having been conceived ‘as television programmes which I could do if […] I had enough power to command a television transmitting station. I too transmit hypotheses, news, advertising, music, poetry, and I entertain …’6

Towards the end of the 1960s, in common with many other artists of the period, Baruchello began to take a more direct approach to the political situation and abandoned his earlier technique of using creative fantasy as a form of mediation. Instead, the ironic and Surrealist nature of his practice manifested through his appropriation of production and distribution methods used in industry, which he employed as a means of scrutinizing art-world conventions. In the series ‘Happenings a distanza’ (Happenings from a Distance, from 1966), for instance, he sent art works directly from his studio to the recipients’ homes, thereby circumnavigating the usual route of using a commercial gallery as intermediary. Perhaps the best-known piece from this series is Multipurpose Object (1966), a contraption reminiscent of a repeating rifle’s reload mechanism, which Baruchello designed to help ‘relax’ us forces in Vietnam. Having followed stringent official procedures, the artist submitted the object to the Pentagon for approval, only to have it returned with a letter declining his proposal.

In 1968, Baruchello launched Artiflex, a company that produced a variety of items of dubious utility – survival rations for shipwrecked castaways, for instance, or a ‘half-jacket’ comprising only the left-hand side – and provided fiscal and business services through its financial wing, Artiflex Finanziaria. One such service involved sending a ‘Theatre Pack’ to anyone who requested one: the packs, however, contained items that would cause the recipient to have an accident.

Following the failure of the 1968 protest movements in Italy, the population became disillusioned, tensions grew and violence escalated. The situation prompted Baruchello to abandon the more direct form of action he had been pursuing and to seek an entirely new way of life and a fresh approach to his art. So, in 1973, he moved out into the countryside near Rome, took possession of some uncultivated land that had been intended for speculative property development, and founded Agricola Cornelia (Cornelia Farming). Defined as a ‘pseudo-political happening’,7 Agricola Cornelia was not least Baruchello’s response to the aesthetic aloofness of much Land art. His exploration of the rural lifestyle and agricultural economy led him to experiment not only with land cultivation and crop production, but also inspired numerous actions, films, paintings and cabinets.

Two further projects, which 20 years later would have been called ‘relational’, also evolved from this farming period: Il Giardino (The Garden, 1973), for which a part of the farm land was reclaimed and transformed into a natural environment that might be considered to be ‘ideal’; and the Fondazione Baruchello (Baruchello Foundation), a kind of think tank involved in cultural research and exhibitions. Moving beyond the scope of traditional art work and, ever more decisively, from the private domain to the public arena and from criticism to participation, Baruchello forged alternative systems that were no longer merely imaginary, but based on fruitful relationships between individuals, and between individuals and the environment. Baruchello replied to Duchamp’s call for silence by – quite literally – getting his hands dirty.

Why, then, is Baruchello’s name missing from the art-historical canon? Despite enjoying collaborations and friendships with some of the most important intellectuals of the postwar period, Baruchello always maintained a unique approach to his art and – perhaps as a result of his somewhat atypical education – remained at a remove from the most significant movements of the last 50 years. His take on the mediated society that was emerging in the 1960s, for instance, didn’t fall into line with the iconic aesthetic of Pop art; while issues such as the individual’s role within the new mass-media society and within the mass-production model of the Fordist economy were addressed in a manner quite at odds with the Minimalist and Conceptualist neo-avant-gardes, which reduced its intricacies to pared-back systems. Baruchello’s approach was closer to that of a narrator who flirts with chaos, who can handle complexity without evading it or reducing it to mere symbols or easily communicable systems. In many respects, his position is that of a Postmodernist before Postmodernism.

And how to explain the recent resurgence of interest in Baruchello’s work? I believe this relates directly to a revival of story-telling in art, after the anti-narrative, abstract stance of much Modernist art of the 20th century; and to how the digitized world in which we now live is predicated on the constant flow and exchange of information, words and images. Typically, Baruchello’s works propose a narrative structure and suggest complex systems of relationships, with labyrinthine associations linking disparate details. Our current ‘fluid modernity’ has witnessed a widespread return to the art of story-telling in fields that are not usually associated with it – such as marketing, journalism, politics and contemporary art. Likewise, the ways in which Baruchello constructs and populates the visual plane in his works, particularly his paintings, is emulated by how we now see words and images in unexpected, and at times absurd, combinations during our now-daily online searches.

More than 30 years ago, Gilbert Lascault wrote of Baruchello’s work: ‘Adventures are offered for the eye and for the senses, for princes and vagabonds alike […] There is no longer a centre; there are no longer boundaries, nor a path to guide you. Each one of us must lose ourselves before finding ourselves again. Each one of us must discover our own itinerary.’8 For anyone today with Internet access, doesn’t that sound familiar?

Translated by Rosalind Furness

1 Gianfranco Baruchello, Breve storia della mia pittura (Short Stories about my Painting), Edizioni Peccolo, Livorno, 2003, p. 5

2 Introduzione a Baruchello. Tradizione orale e arte popolare in una pittura d’avanguardia (An Introduction to Baruchello: Oral Tradition and Popular Art in Avant-Garde Painting), Galleria Schwarz, Milan, 1975, p. 18

3 Ibid, p. 50

4 Jacques Rancière, ‘Is History a Form of Fiction?’, The Politics of Aesthetics, Gabriel Rockhill, London, 2006, p.38

5 P. Cabanne, Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Interviews with Marcel Duchamp), Èditions Pierre Belfond, Paris, 1967, p. 193

6 G. Baruchello, Supericonoscopio. Una conversazione tra Gianfranco Baruchello e Arturo Schwarz, Galleria Schwarz, Milan, 1968, p. 3

7 Carla Subrizi, ‘Piccoli sistemi’ (Small Systems), in Introduzione a Baruchello, op. cit., p. 77

8 Gilbert Lascault, Baruchello ovvero del divenire nomadi (Baruchello, or Becoming Nomads), Il Chiodo arte contemporanea, Mantua, 1977, in Subrizi, op. cit., p. 75