The Turner Prize & Identity Politics

A response to some of the responses

A response to some of the responses

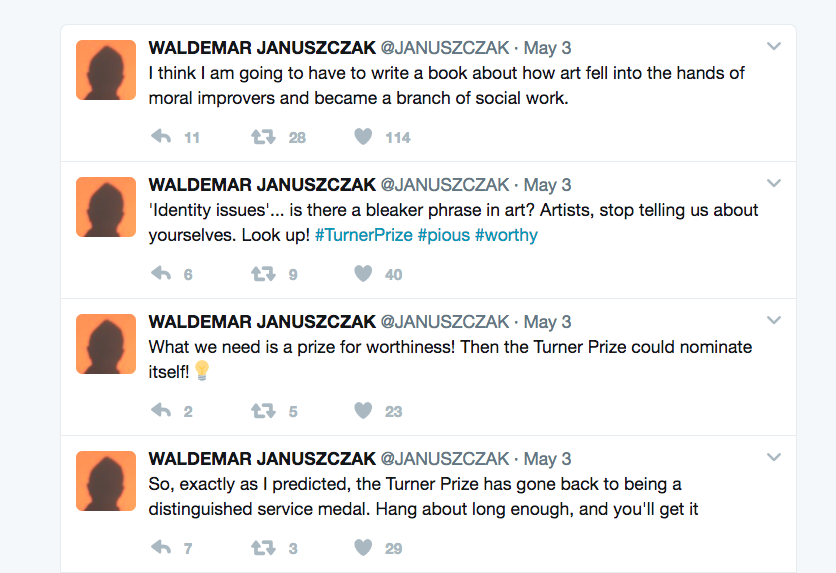

‘“Identity issues” – is there a bleaker phrase in art? Artists, stop telling us about yourselves. Look up! #TurnerPrize #pious #worthy’ So wrote art critic and broadcaster Waldemar Januszczak in one of a series of tweets in response to the announcement of this year’s Turner Prize shortlist. He’s not the only one to have made a troubling comment on the role of identity politics in the nomination of artists Hurvin Anderson, Andrea Büttner, Lubaina Himid and Rosalind Nashashibi (full disclosure, my colleague, frieze co-editor Dan Fox, is one of the prize judges). The online arts publication ArtLyst also chose an outrageous headline for their article on the nominees, running: ‘Turner Prize Shortlist Reveals Obscure Multicultural Pick & Mix’.

I’ll tell you what I find bleak – this kind of complacency around diversity and worthiness in the arts. Though the ArtLyst article includes fairly innocuous descriptions of each artist, indicating that the headline is probably unintentionally ham-fisted, its framing remains problematic in its reference to identity. To liken the selected nominees to a ‘pick & mix’ evokes the image of a mixed bag of goods or confectionary. In its most troubling potential reading, the phrase depicts the artists as an assortment of shapes, colours or flavours, all of which carry associations of racial ‘types’. It’s a headline that implies that the artists were primarily selected for their cultural variety, not their long and rich careers as artists, that their ethnicity is the salient factor behind their nomination, rather than the quality of their work. To label them as obscure is silly. Each has had at least one major local or international exhibition in the last year, all have work in important public collections and are, or have been, represented by influential commercial galleries. Himid, who one could argue out of all the nominees is the least well-known, has had, this year alone, two retrospective exhibitions in UK public institutions (Modern Art Oxford and Spike Island), and her work was included in another large group show, ‘The Place is Here’, that just closed at Nottingham Contemporary. Nashashibi’s films are currently on view in documenta 14 in Athens; Büttner will have a solo show later this year at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles; Anderson recently had a solo show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada. They are not household names, for sure, but if that’s what counts as obscurity then I need to call my agent pronto!

But whilst the article discusses these artists as 'unknowns', the headline may be read as implying more than their relative public profiles. It yokes together the concepts of multiculturalism and obscurity, suggesting, intentionally or not, that the one idea necessarily entails the other. Multicultural politics are often seen as the concern of marginalized ethnic groups, those most in need of better political or social representation. According to this NIMBYist logic, beloved of neo-conservatives, multiculturalism is obscure because it is unimportant to the cultural majority and unhappily imposed upon them by the few. Multiculturalism also carries the taint of liberal elitism and so implies intellectual, academic or economic removal from the realities of everyday life.

The assumed obscurity of the multicultural thus pulls in two different directions: on the one hand it represents the culturally insignificant, on the other, those who are too culturally significant, because they are privileged by the powerful. In the context of the Turner Prize nomination, the phrase ‘obscure multicultural pick & mix’ oscillates between these two ideas, suggesting both the minority backgrounds of the nominees and the rarefied concerns of the judges. At the risk of sounding rather rarefied myself, these polarized meanings put me in mind of Roland Barthes’s parody, in 1957, of the conservative critic who complains about a difficult play: ‘I don’t understand, therefore you are all stupid’. According to Barthes’s imagined malcontent, whatever can’t be readily understood or doesn’t conform to my interests, is dumb, even if that’s because it’s too sophisticated, or simply unfamiliar. Either way, the problem can never be with the one who feels challenged. In regard to the Turner Prize responses the phrase might be: ‘I don’t feel represented, therefore this is irrelevant’. Given these highly charged associations, the pairing of multiculturalism and obscurity is unfortunate.

Let’s take a moment to unpack Januszczak’s tweet. Well, first of all, what kind of person would take to Twitter to make sweeping remarks on urgent and sensitive socio-cultural issues? I’m drawing no obvious comparisons, as I don’t want to encourage Jancuszczak to enter politics.

His singling out of the phrase ‘identity issues’ is an incredibly reductive response to a shortlist of four very different artists. Whilst it’s true that identity does factor into the work of each nominee, some place more emphasis on this than others and each approaches the subject in distinct ways. Himid, perhaps the artist most explicitly associated with identity politics, was at the vanguard of the black British arts movement in the 1970s and ’80s, and was nominated for figurative paintings exploring the impact of colonialism on displaced individuals. Quite differently, Anderson approaches black British identity in his paintings through abstraction, interiors or landscapes. Büttner, to the extent that she could be said to explore identity at all, has done so through her work with Carmelite nuns and displays of native plant life, although the judges singled out her use of anachronistic techniques such as woodcutting as amongst the reasons for her nomination. Nashashibi is a filmmaker whose nominated video, Electrical Gaza (2016) uses animation and live footage to play with truth and falsehood in the Arab-Israeli conflict, a context suffused with identity issues, but not necessarily the primary topic of the work.

Januszczak’s argument seems to be that in dealing with identity artists are fundamentally falling into the trap of narcissism. Are ‘identity issues’ so easily reduced to artistic navel gazing? At the risk of stating the obvious, identity politics are primarily concerned with widespread social and structural issues of inequality, even where they are expressed through the personal. Racism, misogyny, homophobia and class identity are all collective rather than singular struggles and any attempt to draw on biography often serves to situate the individual in relation to their social context.

More than that, artists exploring identity have done much to displace the role of the individual: far from confirming narcissism, the idea that identities are culturally constructed, relative and discursive, would seem to have much more to do with them looking at the broader world of visual culture. Think of Cindy Sherman drawing upon cinema tropes to explore representations femininity, or Himid’s images of colonial history, dress and custom: these aren’t self-portraits in any ordinary sense, but journeys into the history of art, cinema, economics and literature. And, turning back to my phrase ‘I don’t understand, therefore this is irrelevant’, isn’t Januszczak’s own narcissism the spectre haunting his tweet? Identity issues bore him because they are not his primary concern and therefore he finds no urgency or interest in such work. As the young folk say, ‘check your privilege’.

There’s also a striking irony in his complaint about worthiness (#worthy). Whilst Jancuszczak implies that the list has a joyless focus on political reform, isn’t he the one making the much more overt and distinctly sour call for cultural change? Where’s the joy in his bad-tempered tweets? His hashtag invokes the received opinion that art about social issues is, necessarily, dry and dull and presents a picture of cultural progressives as party-poopers. These are such well-worn conservative clichés that they’ve even inspired attempts to reclaim them: for example, in her blog Feministkilljoys, Sara Ahmed encourages her readers to embrace the stereotype of the humourless women’s libber. The implication behind the accusation of worthiness is that happiness and pleasure depend on maintaining the status quo, never mind that this involves a great deal of unhappiness and neglect for others. Anyway, I see a huge amount of playfulness in Himid’s celebrations of black creativity, beauty in Anderson’s paintings and mordant humour in Büttner’s trays of wilting Welsh moss. And if you want art with vitality, you could do worse than grappling with the life and death questions raised in the films Nashashibi made in Gaza. Jancuszczak also tweets that these do-gooders have nominated certain artists (clearly Anderson and Himid) simply because of their age and longstanding commitment to issues of identity, indicating that they are undeserving other than because of their longevity.

Of course, it’s difficult not to hear echoes of Brexit Britain and protectionism in these responses. In the call to turn away from identity issues, isn’t there just a hint of sticking to what we know and recognise? Doesn't the mention of moral improvement sound an awful lot like lazy complaints about political correctness? Adrian Searle certainly seemed to anticipate this scenario when he enthusiastically described the shortlist as a ‘cosmopolitan rebuff to Brexit provincialism’. Cosmopolitans are also, of course, a delicious cocktail and certainly taste better and bring more joy than all these sour grapes.

Main image: Lubaina Himid, Navigation Charts, 2017, installation view, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy: the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London