Wael Shawky Takes on the ‘Dinosaur’ of US Imperialism in the Gulf

The artist’s fantastical sculptures and bas reliefs, on view at Lisson, New York, combine prehistoric creatures with oil barons and kings

The artist’s fantastical sculptures and bas reliefs, on view at Lisson, New York, combine prehistoric creatures with oil barons and kings

A follow-up to ‘Cabaret Crusades’ (2010–2015), his widely-exhibited trilogy of films narrating the Crusades from an Arab perspective, Wael Shawky’s latest exhibition, ‘The Gulf Project Camp’, focuses on the history of the Arabian Peninsula since the 17th century. At the show’s entrance, a hand-drawn map depicting historical regional powers, such as the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal empires, sketches out its geographical scope. If ‘Cabaret Crusades’ traced the origins of European colonialism in the Levant, Shawky’s latest work tackles the American imperialism that followed the discovery of oil there.

A series of large bas-reliefs draw their visual cues from the art and visual culture of the period: from the famous miniatures of Mir Sayyid Ali, active during the mid-1500s at both the Safavid and Mughal courts, to other frequently illuminated medieval texts such as the ‘Khamsa’ of Nizami (12th century) or Jami’s ‘Haft Awrang’ (c.1468–1485). Shawky deftly transforms the characteristic flattened perspective of these vignettes of court life and palace intrigue into interlocking jumbles of richly patterned planes hand-carved out of antique wood or cast from translucent glass. In his monumental painted panel The Gulf Project Camp: Carved wood (after ‘Hajj (Panoramic Overview of Mecca)’ by Andreas Magnus Hunglinger, 1803) (2019), he eerily empties the view in an 1803 panorama of Mecca of its people, situating it in a time before or beyond history. The only sign of life is a dinosaur surveying the site, its long slender neck emerging from a mountain that also stands in as its body. Appearing throughout these works, such fantastical beasts are benign presences, their thickly lashed eyes closed demurely as if lost in thought or reverie. When such creatures are absent, Shawky cleverly renders the craggy terrain surrounding his cityscapes in a manner that suggests scaly reptilian skin, sublimating the mythic into the natural. This monstrous fusion of animal, architecture and landscape is most successful in the accompanying sculptures (four in bronze, one in luminous lavender glass), which suggest scenes from a post-apocalyptic future as much as some primordial past. The sculptures are displayed on an enormous zig-zagging wall, whose crenellations and faux-stucco surface recall the region’s dusty architecture while its teal colour adds another touch of otherworldly whimsy.

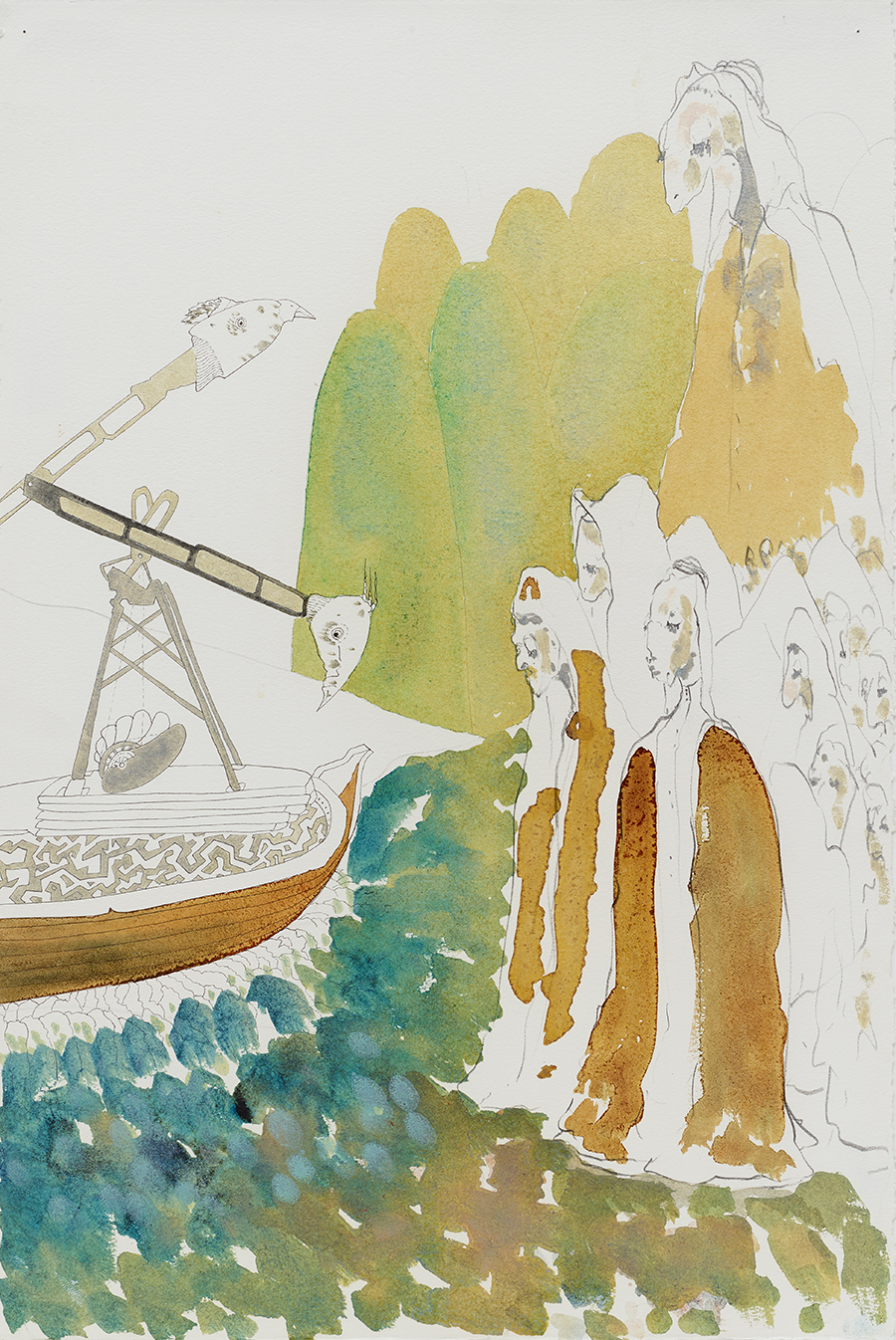

In the back room, a series of wonderfully playful mixed media drawings (‘The Gulf Project Camp: Drawings’, 2019) feels like exploratory sketches for the objects or, perhaps, a mood board for a forthcoming film. Here, historical references are more overt, featuring images of key power players who have shaped the Gulf – from the nineteenth-century Ottoman general Ahmed Mokhtar Pasha to more familiar faces, such as Ayatollah Khomeini, Richard Nixon and King Faisal. The machinery and infrastructure of oil extraction and transportation also appear: a tanker filled with cylindrical vats, a wrecked oil truck, various boats, airplanes and even a submarine. In Abdelrahman Munif’s epic Cities of Salt (1984), one of the few literary texts that narrate the effects of oil’s discovery on the region’s desert-dwellers (a copy of which sits on the gallery’s front desk), the natives regard such monstrous modern intrusions with fascination and fear. Shawky visualizes this apprehension: the bobbing ends of derricks are transformed into beaked avian heads, while camels in cowboy hats and suits caricature American oilmen.

In interviews, Shawky has discussed his use of myth, metamorphosis and the monstrous as strategies for challenging the authority of history. In these surreal drawings satire emerges as an effective mode of critique in a region where history continues to be heavily contested and is often dictated by the state. They also capture the absurd speed and scale by which the oil boom jolted nomadic communities into futuristic urbanization. Shawky brilliantly illustrates this transition – which profoundly scrambled traditional ways of living in and understanding the world throughout the Gulf region – as a chair swing ride that resembles a mechanized palm tree, or a supersized cheeseburger mysteriously floating out at the sea.

Wael Shawky, ‘The Gulf Project Camp’ continues at Lisson Gallery, New York, USA, through 16 October 2019.

Main image: Wael Shawky, The Gulf Project Camp: Desertscape # 1, 2019, oil on carved wood, 575 × 290 × 18 cm. Courtesy: © Wael Shawky and Lisson Gallery