What Audre Lorde's Language of Self-Care Can Teach Us After #MeToo

At transmediale in Berlin, contesting exclusionary language from the alt-right to offshore finance

At transmediale in Berlin, contesting exclusionary language from the alt-right to offshore finance

In her keynote presentation at Berlin's transmediale last weekend, Lisa Nakamura noted how many speakers had quoted poet, feminist and civil rights activist, Audre Lorde, during the first three days of the festival. With a theme this year of 'face value', the art and media conference's programme of talks, screenings, performances and exhibitions interrogated the image of finance, scraping at the surface of how capitalism implicates bodies through labour and inequality. It was as much about the value of faces as taking things at face value. Lorde's language of self-care is in itself a political act, insisting on the enduring existence of vulnerable bodies; the burgeoning trend of quoting her poetry indicates the extent to which the egalitarian technological dream has failed. Post-Trump and post-#metoo, where digital culture has both exposed and produced polarizing inequalities, can Lorde's vocabulary of self-preservation help us reconnect with our bodies as a political weapon?

Digital media and race scholar Lisa Nakamura used Lorde to illustrate how closely 1980s 'women of colour feminism' speaks to the current era. WOC feminism shares its roots with the birth of the internet, which Nakamura argues is no coincidence: the utopian promises of both movements have differed in their success levels, yet life remains precarious for women of colour in 2018 both under Trump and on the internet. Nakamura's talk called for a 'speaking back' to the online spectacle of black pain (highlighting Google's VR 'immerse' experiences of a day in the life of their black female employees as a particularly misfired empathy device) – and for a rally against the excluding vocabulary of technologies (such as Nintendo's Game Boy and failed 1990s experiment Virtual Boy – where are the Game Girls?). Taking the internet users who compiled and disseminated a 'Lemonade Syllabus' to enable a wider understanding of Beyoncé's 2016 album as an example, Nakamura proposed that this language could open spaces for the complexities of womanhood to exist online.

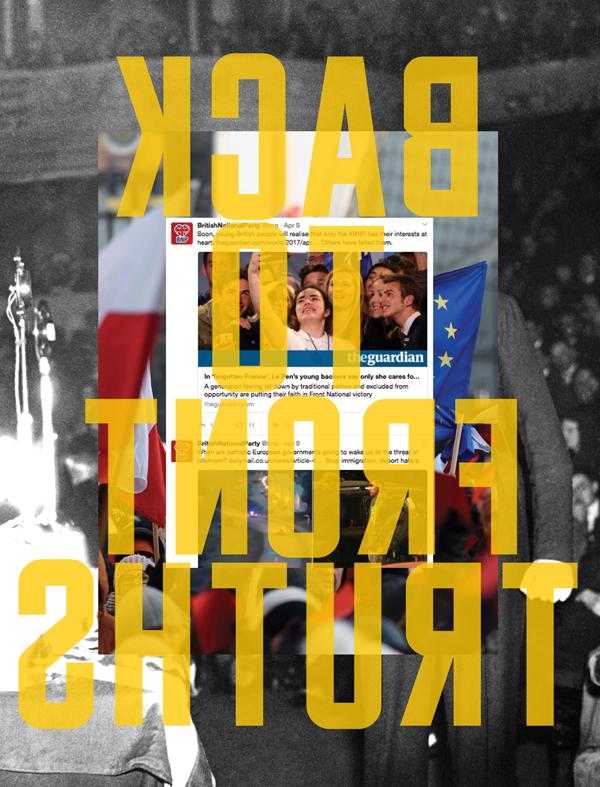

Where language took on a poetic role for Nakamura, it performed its incendiary capacities for Nick Thurston's Hate Library (2017), installed in the foyer of Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Produced over several years in collaboration with historian Matthew Feldman, the work reproduces the writing spouted by Europe's far right on online forums, printed as a wallpaper backdrop around a circle of orchestral music stands, upon which rest ring-bound books of further extremist conversations, arranged by country. Printed, bound and poised on a lectern, the work quite literally represents the performance factor of offensive rhetoric, underscoring the humanity behind the online troll and our close proximity to far-right viewpoints. Beyond merely embodying this language, Thurston's installation problematizes our spatial metaphor for the political spectrum, which implies a neutral centre ground that in reality is always shifting in relation to the extremes. Hate Library advocates for an increased literacy to contest the alt-right, yet, in constructing a library-as-artwork, perhaps some of this gets lost in the image-making process.

If a library can be an artwork, can Companies House be used as a gallery? Artist collective Demystification Committee's investigation-from-within of offshore financing structures playfully proposes the business registration service as such. Having registered a company in Brixton, London, the artists then entered the bizarre online forum world where users rate and review offshore proxy agents, eventually ending up with their business spanning three oceans through a number of puppet directors. Presented at transmediale through company certificates, letters, credit cards and the actual product, the Offshore Spring/Summer 2018 collection of 'beachwear', the artists co-opt and thus expose the peculiar vocabulary through which the hidden offshore world operates. Inherently secretive, with the companies' surface 'face value' acting primarily as a shield for its real operations, the most surreal aspect to Offshore Investigation Vehicle is its total legality, as we've seen through the revelations but lack of repercussions following the release of the Panama and Paradise Papers. When uploading their artistic documentation to Companies House's online portal, the registry was perfectly happy with the artists stating they were avoiding tax (not illegal, whereas evading tax is) – their only issue was that the text should be more legible on the page. This process of written correspondence ultimately becomes utterly divorced from the original company directors – the Demystification Committee – before coming full circle, proposing a swimsuited body sunning itself in paradise.

The continued abstraction of the financial world imagines and images it as a world of suited male handshakes, at a far remove from our daily lives. Yet contemporary art sits at the bleeding edge of capitalism, a commodity both complicit and contestable. For a festival dedicated to online culture, transmediale served to remind us of the offline bodies intrinsically bound up in capitalism – through slavery, labour, migration – and demanded that we activate our bodies by speaking up and out in resistance. At points throughout the sprawling programme, an enduring tendency to soundtrack moving image works with automated voices seemed outmoded, a naïve relic of postinternet art. This digital insularity has all too often magnified society's existing inequalities – rather, it is in dialogue with other humans where divisions might be crossed, transcended and broken, in a new politics of care.

Main image: Heather Dewey-Hagborg and Chelsea E. Manning, A Becoming Resemblance, 2018. Courtesy: transmediale, Berlin; photograph: Andreas Hirsch