What the Instagram Age Learned from Robert Rauschenberg’s Choreographic Pieces

Performed images in contemporary art and everyday life

Performed images in contemporary art and everyday life

Everyday performance abounds. On bridges and pavements, at airports, aboard planes, at congresses and protests, social and cultural events, in the mirrors of communal toilets. Performers angle towards lenses implanted in phones, installed with image-sharing applications. Images are taken to move across media platforms. There are myriad factors attributable to this propagation, but it’s facilitated by developments in technology and changes to the economy. People self-position, build profiles, accrue followers – sums married, reputedly, to opportunity.

A new wave of choreographic strategies in galleries and museums reflects these activities, the compulsions behind them and the cultures that foster them. Exhibition architectures afford visitors a different depth of perspective than the arm’s length between smart screens and users’ eyes. Artists choreographing images-in-circulation adumbrate one great contradiction of our time: a creeping sense of social exclusion despite proliferating platforms for self-representation. We are divided.

Ties between accelerated technological change, image distribution and political disorder have precedent. The 1960s saw huge advances in the quality, rapidity and range of broadcast technologies and print media, which enabled the swift relaying of images of labour strikes, protests and the civil rights movement, alongside those of the war in Vietnam. Different domains of social unrest became interconnected. There was great change in art, too, and the media artists adopted to make sense of it all. ‘MY FASCINATION WITH IMAGES OPEN 24 HOURS,’ wrote Robert Rauschenberg in a short, idiosyncratic note in 1963. Technological excitement jostled with unease about the future as he moved towards performance, a medium that suited his appetites: media-curious, information-hungry, image-responsive, nocturnally active and fiercely, perhaps gnawingly, social. For a time, performance allowed Rauschenberg what ‘the loneliness of painting’ could not.

Influenced by his experiences at Black Mountain College in 1949 and 1951–52, with its assimilation of Bauhaus principles and ‘stage studies’, Rauschenberg worked for many years with Merce Cunningham, John Cage and the Judson Dance Theater as a set, costume and lighting designer. He performed with the Parisian kineticists Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle and collaborated with the Bell Laboratories electrical engineer Billy Klüver as part of Experiments in Art and Technology. His 11 choreographic pieces from 1963–67 (others remained undocumented, unfinished or were collaborative) display some key qualities we see in major works of performance today, where dance is treated less as an inherited or rigorous set of movements or principles than as a means of activating or inhabiting patterns of image circulation and absorption.

Dancer and choreographer Steve Paxton recognized Rauschenberg’s own unique qualities as a choreographer. ‘Movement can be generated in a variety of ways,’ Paxton wrote in a catalogue essay for Rauschenberg’s 1997 Guggenheim Museum retrospective, ‘and [Rauschenberg] generated his by couching people within images and then allowing images to coexist, collide and follow one another.’ Distinct from Judson’s task-orientated movements plotted for non-proscenium environments and the moderately interactive arrangements of Happenings, Rauschenberg’s was a dynamic, nonnarrative image performance oiled, but not defined, by dance. His compositions of overlapping and co-existing images responded to a new density of media visuals filling up the living spaces of the 1960s.

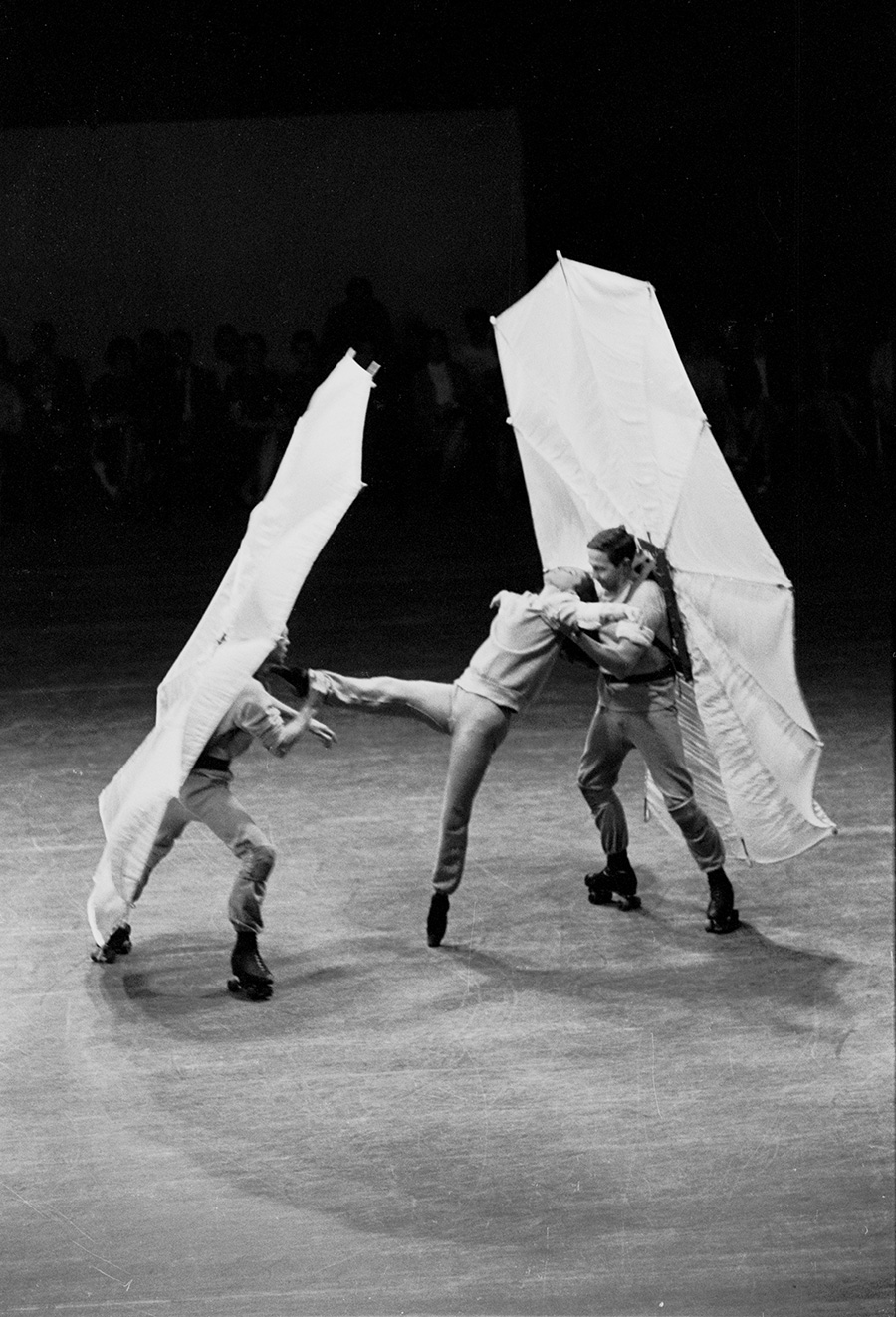

Image combinations were evocative. In Pelican (1963), Rauschenberg and Per Olof Ultvedt glided on roller-skates, stilted parachutes attached to their backs, swooping like odd-winged creatures around Carolyn Brown’s elegant balletic phrasings. This was accompanied by a sound collage of telephones, car horns, crickets stridulating, pop songs and classical music, a combination that, Paxton recalled, ‘sounded like it was being broadcast in a parallel universe’. Dedicated to the Wright Brothers, the piece interlaced different human attempts at flight in an ode to technology.

In Urban Round (1967), in front of an enormous, silk-screened backdrop featuring the introductory colourbars of a film or videotape, and dispersed photographic images transferred from various news sources, performers were carried around and through the seated crowd on brightly coloured stretchers. They read aloud, backwards, from selected newspaper articles, performers switching places after every article, on rotation. Garbled information, like the performers themselves, was in constant circulation.

Approaches by a number of contemporary artists correspond fascinatingly with aspects of Rauschenberg’s output of this period. In Anne Imhof’s recent body of work (Sex, 2019, Faust, 2017, and Angst, 2016), performers appear as, or within, images, while new technologies mobilize images and sounds within the locomotion. These methods also appear in Ligia Lewis’s minor matter (2016), albeit in ways critical of how images-in-circulation have worked to objectify or exclude black bodies, using lighting to illuminate and estrange her dancers’ interactions. Boris Charmatz, like Imhof and Lewis, seems acutely aware of the potential reach and damage of widely circulated images and, in Danse de nuit (Night Dance, 2016), explored their function in crimes of terror. Imhof and Charmatz manipulate their viewers’ lines of vision while dancers purposely disperse crowds around ever-expanding stages. Finally, all have collaborated with different artists of compatible resolve, working across media with movement, sound and light. Rauschenberg presented a choreography of image circulation, long before this strategy.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 206 with the headline ‘When Images Move’.

Main Image: Eliza Douglas in Anne Imhof, Faust, German Pavilion, International Art Exhibition – La Biennale diVenezia, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York; photography: Nadine Fraczkowski