The Whole Truth

Many artists today recognize that environmentalism needs to embrace political, social and economic factors as well as ecological ones

Many artists today recognize that environmentalism needs to embrace political, social and economic factors as well as ecological ones

‘You don’t need a Ph.D. in linguistics’, write US political strategists Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus (authors of the 2004 report The Death of Environmentalism), ‘to see that there’s something funny about the concept of “the environment”. If the concept includes humans, everything is “environmental”, and it has little use other than being a poor synonym to “everything”. If the concept excludes humans, it is scientifically specious (not to mention politically suicidal).’1 As if shadowing Shellenberger and Nordhaus, a number of recent artistic projects also suggest that the literal sclerosis embedded in antiquated concepts of ‘environmental issues’ and ‘nature’ isn’t up to comprehending the ecological – and thereby political, social and economic – territories of our time.

Why is housing for indigenous species, for example, an ‘environmental issue’, whereas housing for humans isn’t? Jeremy Deller is perhaps best known for his re-staging of a violent clash during the 1984–5 miners’ strike (The Battle of Orgreave, 2001), the fall-out from so much more than the ‘environmental issue’ of burning coal. Yet his practice has long been concerned with other marginalized communities, notably urban cyclists – and bats. For his Bat House Project (2006–ongoing) he is collaborating with The London Wetland Centre to run an architectural competition to realize a bespoke accommodation facility for clients of the flying mammal variety. The artist treats quality accommodation, decent living standards and urban space as areas of concern for both the human and the non-human residents of the capital. Projects such as this naturally have their precedents – artists have long engaged with issues of ecosystem restoration and with collaborative or ameliorative practices. But just as the provincial sentiments that gave birth to the popular environmental movement could never have anticipated Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth (2006) – never mind the rather blithe reaction to the 50/50 prospect of catastrophic global systemic meltdown predicted by the likes of the Stern Report – the rules of engagement for artists and all other citizens today involve an entirely different, far more insidious and pervasive ecological theatre.

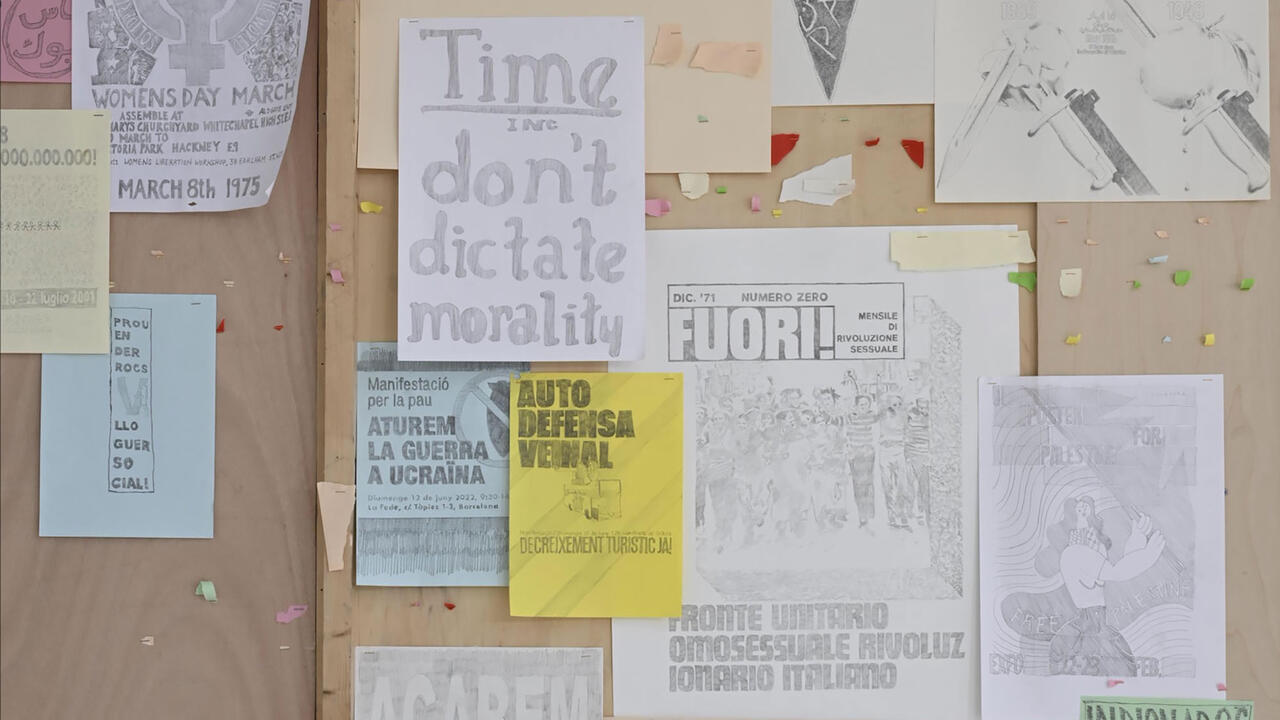

Since emerging in the early 1970s, American artists such as Helen and Newton Harrison and Alan Sonfist have been making work about ideas concerning the rehabilitation and remedy of habitats. Yet it’s fair to say that, unlike the warming globe, the broader reception of work identified as ‘eco-art’ or ‘environmental art’ has always been somewhat cool. Meanwhile in the UK the countryside romanticism brand of knitted twig or snowball sculptures by artists such as Andy Goldsworthy – although, somewhat ironically, hugely popular as ‘dead tree edition’ coffee-table books – has largely marginalized itself by tacitly enforcing a rural nostalgia. On the one hand, as with other liminal areas of art practice (‘live art’ would be another case in point), the commercial and institutional art system’s seeming reluctance would be interpreted by some as a metropolitan conspiracy. On the other hand, that self-proclaimed environmental artists tend towards a practice of glorified landscaping or aestheticized surveying – or, dare I say, a certain lumbering Kumbaya-ism at its extremities – would lead others to conclude that it’s simply part of a distinct creative lineage. As a familiar argument goes, laudable motives, burdened by guilt about making the ‘correct’ ethical choice or holding onto a vision of virgin nature, are often only fleetingly successful as art. Above all this, however, is the simple fact that the narrow environmental imperative that gave birth to such art practices surely has limited traction in today’s world. The notion of environmental art apparently has little clout as environmentalism either. Despite, or because of, the fact that many of environmentalism’s key achievements, such as clean air acts, wilderness preservation or endangered species legislation, have since been gutted by the likes of the Bush administration, acting as a special interest group is no longer a strategy that makes sense. So what might post-environmental art be?

One expansive creative lineage might be tracked back to the early ‘systems’ works of Hans Haacke or the ongoing practice of Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Ukeles has been working with The City of New York Sanitation Department and around the Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island since the mid-1970s and has developed an approach that shares performative and documentary elements with a social and political dimension. Admiring the classical American Earthworks but troubled by their ‘unfortunate un-public aspect’ – often being isolated or on private land – Ukeles instead turned her attention to the monstrous Fresh Kills dump, both as a ‘50-year-old social sculpture that we have all produced’ and as a way of exploring the massive municipal system of disposal of what the city has thrown ‘away’ and hoped to forget. For her ‘Touch Sanitation’ (1978–80) Ukeles spent 11 months following garbage truck crews in every borough of New York, personally greeting each of the city’s 8,500 sanitation workers with a handshake and the salutation: ‘Thank you for keeping New York alive.’ By exploring the operational function and channels of the city as an organism – encroaching on both human and non-human alike – works such as ‘Touch Sanitation’ show a capacity to trace previously hidden pathways and ‘up-cycle’ meaning, if showing the habitual industrial mechanisms for the literal burying of resources in the world’s biggest dump. On 13 September 2001, having been shut down and slated for remediation just months earlier, Fresh Kills was reopened for the burial of debris from the World Trade Center following 9/11 – incinerated human remains now share a graveyard with rubbish. So is terrorism an ‘environmental issue’?

The reality of today’s ecological front line is that the major battles are being lost (and occasionally won) not in woods and marshes but in courtrooms, boardrooms, war rooms and international protocols – and, of course, within psychology and language itself. (Attempts to discredit global warming favour the use of the term ‘climate change’ because ‘people like change’.) The fact that the battle-lines have become increasingly asymmetrical, abstract and more concerned with processes and issues that aren’t black or white – or hair-shirt Green – makes research-based or speculative, documentary-like modes of address in practice more keenly equipped than ever to intervene and infiltrate. And additionally, after decades of image-led, wilderness-obsessed forms of ‘environmental’ consciousness (all polar bears and soft-focus sequoias), practices with a Conceptual basis offer a more relevant traction in a perhaps not unfamiliar new eco-territory where so-called carbon ‘offsetting’ or corporate green-washing, for example, suggest a far more immaterial agenda. Take a recent work by Tue Greenfort, Exceeding 2 Degrees (2007), made for the recent Sharjah Biennial. The artist asked the conservators at the museum venue to modify the air-conditioning and raise the temperature by two degrees Celsius for the duration of his exhibition – such a rise being the threshold for an increase in global average temperatures beyond which, according to the EU and the Stern Report, lie drastic consequences. The resultant work simply consisted of a polythene-sealed barrier that made the ‘breathing’ of the air-conditioning visible as it swelled and contracted. Next to it, a thermohydrograph and its paper plotter documented the AC system and calculated how much electricity, and thus money, would be saved by the venue. The resultant net energy saving would then be used to purchase of an area of rainforest in Ecuador, a gesture that knowingly acknowledges both futility and responsibility.

Similarly, the work of Simon Starling has frequently traced the ebb and flow of value and energy within both natural and cultural ecosystems. In Kakteenhaus (Cactus House, 2002), for example, Starling dug up a cactus from the Tabernas desert in Andalucía, Spain – drylands that are getting bigger as a result of global warming. He then drove the plant in his Volvo estate car to Portikus in Frankfurt am Main, where the cactus (a highly energy-efficient organism) was potted in the gallery and the car’s marooned petrol engine (a highly inefficient system) was kept running in the space. Connected by all the necessary pipes and wires to the Volvo idling outside, the engine heated a circuitous temporary hothouse. The exercise was made even more absurd by the knowledge that the Tabernas was the desert where Sergio Leone filmed many of his spaghetti westerns, and the particular cactus species, a native of the Americas, was probably brought back by a conquistador many centuries earlier.

Christina Hemauer’s and Roman Keller’s current project, A Moral Equivalent of War: A Curiosity, a Museum Piece and an Example of a Road not Taken (2006–7), also concerns a manifestation of power and, like the work of Greenfort or Ukeles, offers itself not as a didactic polemic but as a reordering of energies, resonance and Conceptual nutrients. The project revolves around the artists’ search for the solar panels that former US President Jimmy Carter had mounted on the roof of the West Wing of the White House. Installed in 1979 during an apparent moment of awareness of the dangers of the US’ dependence on foreign oil at the peak of the so-called second energy crisis – at a time when Carter called for 20 percent of American energy to come from solar power by the year 2000 – the panels and all they symbolized were torn down under the Reagan administration in the 1980s. They eventually found their way to a dining-room roof at ‘America’s Environmental College’, Unity College in Maine, but are now long defunct. Hemauer and Keller strapped one of the panels to the roof of their car and drove from Maine to the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum in Atlanta, filming a documentary along the way, meeting Carter himself, transforming the panel into a museum exhibit and reopening a dialogue about present energy policy.

In a very different way Brazilian artist Maria Thereza Alves – who co-founded Brazil’s Partido Verde (Green Party) in 1987 – is also concerned with the past’s commentary on the present and with actions that reawaken dormant human history. As is the case with waste, a weed is not something that natural ecosystems understand – both are entirely man-made inventions. Alves’ particular interest lies in the phenomenon of so-called ‘ballast flora’, a marginal area of botanical study that she herself has effectively pursued under the auspices of an artistic enterprise and which encroaches on mercantile histories and colonialism, global commodities trading and displacement. Today modern cargo ships take on water as ballast to stabilize an unloaded vessel, but in previous eras of maritime trade sailing ships would use earth, stones or sand as ballast if their load of colonial goods was too light – material that could easily be discarded to free up the ship to pick up profitable slaves. Consequently over thousands of years tonnes of this filler material and its attendant seeds and organic matter from the new world was dumped ashore on arrival around the major port cities of Europe. For her ‘Seeds of Change’ projects in Marseille, Liverpool, Exeter, Bristol, Dunkirk and other sites – always where no previous studies of ballast flora have been undertaken – Alves sought the location of ballast spoil sites through old maps, port records and rumour, taken earth samples and endeavoured to germinate whatever archaic seeds have been lying dormant in the substrate. The resultant presentations have gathered the textual and photographic evidence – as well as the plants themselves – and often involved the collaboration of local residents. Gardeners near the Finnish port of Reposaari, for example, had apparently been proudly tending unknown exotic plants for years. In other instances there was so much ballast coming into port that, as is the case in Liverpool, it was often used to build the foundation for new roads – hence plants from Asia, Africa and the Americas can still be found sprouting from cracks in undeveloped niches of the city. Thus since the ‘discovery’ of the New World – a very short amount of time in botanical terms – there has been an exponential increase in non-native, ‘alien’, ‘invasive’ flora arriving, surviving and thriving unofficially in Europe, and an embedding of the colonial project as an overlooked, displaced botanical legacy in the ground. All of which prompts the questions: could slavery be described as an environmental issue?

By conceiving of ‘materials’ – bats, landfill, cactus, engine, solar panels, air-conditioners, weeds and so on – synchronically, as instantiations embedded in space and time, wrapped in a daze of trophic process and streams of history, the profoundly ecological work of art may approximate a design-object scenario that Bruce Sterling has christened the ‘spime’: no longer an artefact or a product ‘the spime is a set of relationships first and always, and an object now and then.’2 Nevertheless, whatever else these aleatory projects may have in common – not least the assertion of the human species’ place in ecological thinking – it’s clear that for them previous parsimonious ideas about what is ‘environmental’ can never be sustainable.

1 Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus, ‘Death Warmed Over’, The American Prospect, vol. 16, no. 10 (September 2005), p. 30

2 Bruce Sterling, Shaping Things, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2005, p. 77