Why Manga Shouldn’t Pretend to Be High Art

The British Museum’s survey of Japanese comics plunges us into their strange, visionary wonderlands

The British Museum’s survey of Japanese comics plunges us into their strange, visionary wonderlands

‘What is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?’ Lewis Carroll’s Alice wonders just before she sees the White Rabbit, and her adventures in Wonderland begin. In Japanese culture, Isekai means ‘another world’ and refers to stories where the protagonists suddenly find themselves in a strange location, like Alice, full of trepidation and wonder. Manga is such a world.

Reputedly the largest exhibition of its kind outside Japan, the British Museum’s ‘Manga’ show aims to satisfy the committed comics veteran, without overwhelming the curious beginner. It is almost an impossible task. Great care has been taken however throughout ‘Manga’ to provide an authoritative tour of the medium. Given the subject matter is vast and teeming, the exhibition is rationalised into six sections with the first explicitly dedicated to understanding the artform; instructing the basics, like reading panels from right to left. There is even a White Rabbit guide called Mimi-chan (created by the mangaka Fumiyo Kōno). The invitation is, effectively, to descend into the rabbit hole, like Alice, and witness the strange world within.

Perhaps real magic can only occur in the half-light, and ‘Manga’ shines awfully bright on the art form. The best parts of the impressive exhibition are those when the map is momentarily lost and the viewer has a chance to explore and immerse themselves in the works themselves. It seems unfair to criticise ‘Manga’ for its depth and diligence but there is a subsequent sacrifice of impact. For once, more spectacle would be welcome. Where is the sense of awe you might feel chancing upon Hayao Miyazaki’s otherwordly Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1982-1994), the future-shock acceleration of Katsuhiro Otomo’s post-apocalyptic Akira (1982-1990), or the dark mystery of Naoki Urasawa’s thriller Monster (1994-2001)? There is no shortage of cinematic verve or heartfelt beauty in featured works like Takehiko Inoue’s shogunate swordsman epic Vagabond (1998-2015) and Akiko Higashimura’s semi-autobiographical Blank Canvas: My So-called Artist’s Journey (2012-2015) but I found myself, in more sedate and academic moments, longing for something unapologetically-Mecha (the giant combative robot genre of manga) to suddenly burst through the walls. There’s little doubt that ‘Manga’ is a superlative education, especially for those involved or interested in creating comics, but it seems indicative that when we come across the iconic figure of Astro Boy (1951-), Osamu Tezuka’s robotic boy wonder, he’s in a glass-case.

When it’s good, and especially if you enjoy an analytical approach, ‘Manga’ is excellent. The curator Nicole Rousmaniere has an eye for treasures that illuminate different aspects of the form. Jazz music is brilliantly visualised in Shinichi Ishizuka’s Blue Giant Supreme (2017-). Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms (2003-2004) by Fumiyo Kōno demonstrates how comics can tackle the darkest chapters of history (in this case the atomic destruction of Hiroshima) with profound emotional resonance. Golden Kamuy (2014-) by Satoru Noda is an exhilarating and intriguing story that touches on the lives of the Ainu people amidst a climate of violence and the harsh but beautiful environment of Hokkaido. Focusing on the passing of seasons and ultimately human life, Moto Hagio’s The Willow Tree (2007) is as bittersweet a meditation on time and mortality as that of any artform. There are surprises even for grizzled old comic book nerds; I had no idea of the cultural impact sports manga, like Yōichi Takahashi’s footballer Captain Tsubasa (1981-1988), have had. All of life is here it seems, even if the darker currents of manga culture, from the myriad forms of erotic hentai to the more alienated and alienating aspects of otaku culture (a term akin to ‘geek’ but often used in a more disparaging sense), are only referenced briefly. It’s frustrating that an exhibition that is clearly driven by the desire to engage with social issues should be tentative in delving too far below the surface.

One useful way of navigating is by using established artforms from the past as waypoints. The exhibition follows the many threads that led to manga from the astonishing satirical Scrolls of Frolicking Animals ‘Chōjū-giga’ of the monk Toba Sōjō, created, it is thought, in the 12th century, to the mythological creatures and stalwart heroes of the last great Japanese woodblock artist before the modern age, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. The genius of Hokusai looms large with his comparatively obscure illustrations being one of the revelations of ‘Manga’. As is the vivid Shintomiza Kabuki Theatre Curtain, by Kawanabe Kyōsai (whose irreverence was more proto-manga perhaps than the curtain), from 1880. So intriguing are these ancestors that the subject seems worthy of an exhibition in itself; the explosive dynamism of the samurai battles of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), for one, would call to mind the skirmishes of manga superheroes. For all the many precedents, it’s difficult to see manga being remotely the force it is without the existence of the singular visionary Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), who was inspired to create ‘stories where good always prevails over evil’ after witnessing the firebombing of Osaka, and later enduring a violent humiliating encounter with an American GI. As ‘revenge’ goes, it’s a beautiful, peaceful, hopeful one, fuelled by a humane indignation at its heart.

All in all, ‘Manga’ surveys a rich and complex art form comprehensively and with no shortage of passion for the craft and the power it has had to enrich lives. Though it is still a booming industry, worth billions, it faces challenges from societal and technological change. It will no doubt synthesise as it has always done (with cinema, anime, games, and so on), especially if the success of the augmented-reality mobile game Pokémon Go (2016) is anything to go by. The exhibition shows how the art form has become part of Japan’s soft power abroad and how it has permeated civic life within the country – for instance, in the form of ‘Let’s take the subway’ advertising from Kyoto. Whether manga’s actual creators can thrive, on the other hand, is a perpetual concern. The art form will no doubt continue to reflect and cater for all varieties of experience in Japan: the urge to escape and the need to belong, societal change and intransigence (Gengoroh Tagame’s My Brother’s Husband, 2014-2017, is a fine case in point, dealing subtly and profoundly with the costs of homophobia between loved ones).

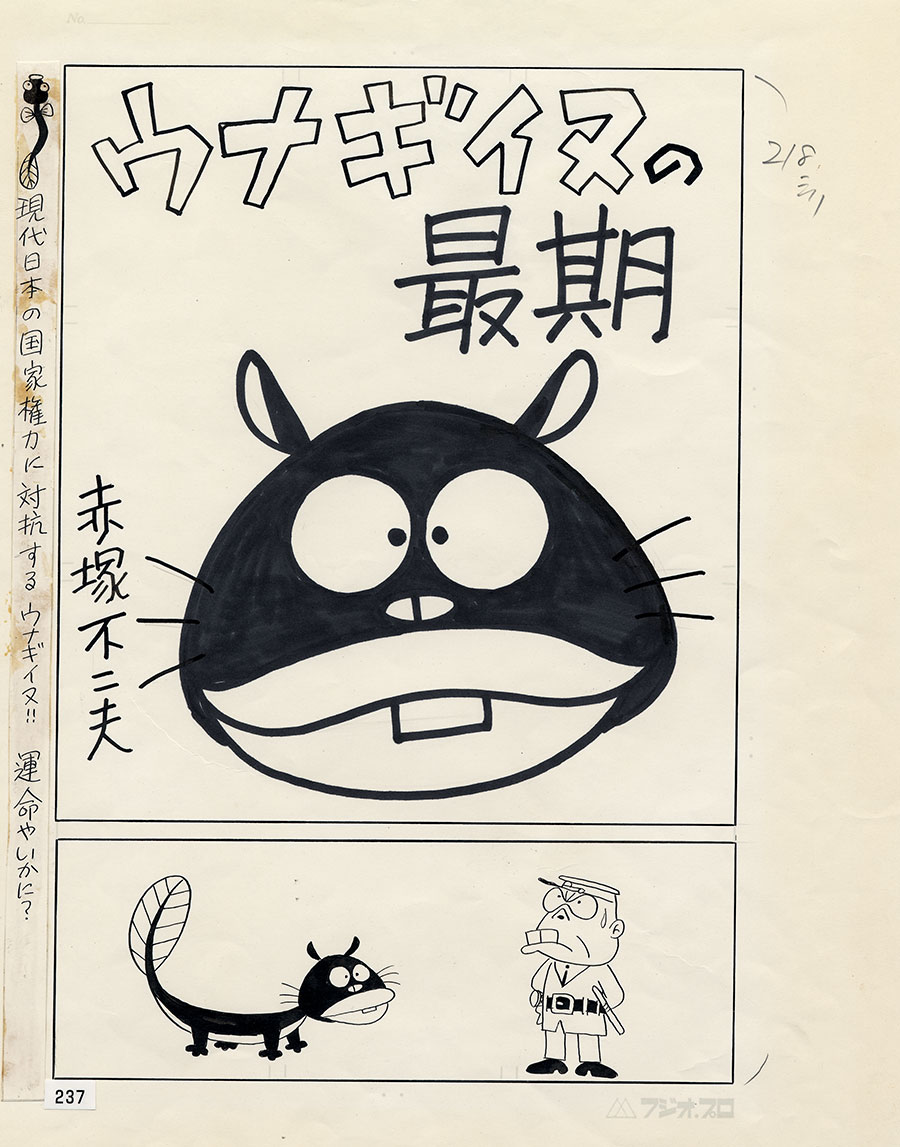

Critics will lament that such a disposable medium does not belong in an esteemed, if controversial, museum. Yet if you wish to remotely understand a place and time (and those who lived there), it is unwise to dispose of disposable things. They tell us a great deal. The temptation is to respond to derision or faint praise with claims that manga can rise to the level of great art, providing stunning examples such as the neo-Piranesi atmosphere of Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame! (1996-2003) or Moto Hagio’s exquisitely florid ongoing work, which reaches deeper into human souls than most of the practitioners of Art Nouveau or the Pre-Raphaelites ever did. This is to play the wrong game however; one that constricts while pretending to elevate. Manga doesn’t need to be high art. Manga is manga. It has different ways of being appraised. It has different functions, strengths and rules to fine art, as this exhibition studiously shows. Look how composed something as gleefully silly as Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball (1984-1995) is or how the childish comics of Fujio Akatsuka (1935-2008) can be gently instructive as well as anarchic. Comparisons with other art forms can be interesting diversions but diversions they remain. Manga is its own world, shown here not quite by plunging down the rabbit hole as we might have but rather reflected meticulously in the looking glass.

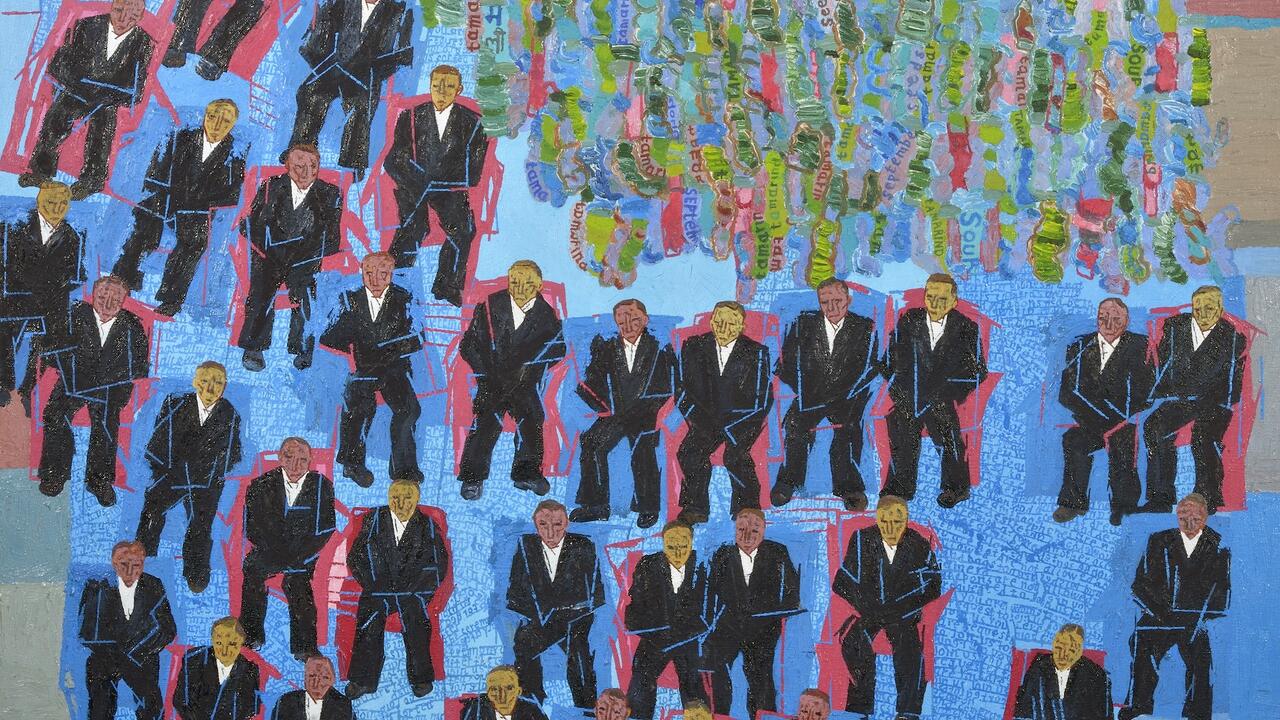

Main image: Kawanabe Kyōsai, Shintomiza Kabuki Theatre Curtain, 1880. Courtesy: Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University