Women in the Arts: Mary Kelly

‘The biggest hurdle we had to overcome was psychological: the belief that there never had been, and never could be, great women artists’

‘The biggest hurdle we had to overcome was psychological: the belief that there never had been, and never could be, great women artists’

For our series celebrating the achievements of women in the arts, the Los Angeles-based artist shares her experience of ‘breaking the canvas ceiling’, the discriminatory division of labour and how women’s collaboration has changed the arts for the better.

What, if any, were the difficulties of embarking on a career in the arts as a woman?

Until the 1970s, the artist, by definition, was assumed to be a man. He could incorporate the feminine as a transgressive gesture, but to be an artist and a woman was like a double negative. Difference subverted the universal category of greatness and that was the biggest hurdle we had to overcome because it was psychological: the belief that there never had been, and never could be, great women artists.

What specific experiences have you had that shaped your understanding of gender in the workplace, the media and the arts?

Of course, when I was starting out, institutional discrimination was more visible and it was systematically challenged by feminist activists on many fronts. Women artists, for example, were preoccupied with what I suppose you could call ‘breaking the canvas ceiling’: things like representation in major museum collections, exhibitions and so forth that reflected the equal rights agenda at the time. Personally, I’ve experienced the weight of that ceiling and, occasionally, even made some small holes in it. My show at the ICA in London in 1976 was the first and only one by a woman in the lineup of conceptual artists presented at what was called the New Gallery then. In 1984, I was the first woman to receive the Arts Council Artists Residency at Cambridge University and, subsequently, this led to the founding of the first major collection of work by women artists in the UK. I think my course on Women and Art at Camberwell College of Arts in the early ’70s was the first of its kind in the UK, too. And, more recently, when I joined the faculty at UCLA in 1996, I was surprised to learn that I was the first woman to be appointed full professor in art, even at that late date.

But what really shaped my understanding of gender in the workplace, or ‘the social/sexual division of labour’ as we called it then, was what I learned while making the film, Nightcleaners (1970–75), the installation Women & Work (1975) and Post-Partum Document (1973–79). To make a long story a lot shorter, during conversations with the cleaners and factory workers, as well as from my own experience – I had my first child then – I came to realize that a woman’s role as mother underpinned her secondary status at work in two significant ways: one was obvious, that is, childcare meant restricted hours and lack of promotion, but the other, more subtle, was the internalization of that role that made the discriminatory division of labour seem natural and expedient.

As you were starting out in the arts, what were the possibilities for mentorship, collaboration and cross-generational engagement among women?

None.

What has changed today?

Well, that’s exactly what’s changed. Today, there are two generations of feminists who have been mentors for younger women and there is so much cross generational engagement within institutions, across institutions and outside of them. Many artists have collaborated with their students on major projects inspired by feminism including Carrie Mae Weems, Suzanne Lacy and myself, but this is the rule now, rather than the exception.

What are your thoughts about #Metoo and other initiatives to call attention to sexual harassment?

With the emergence of #Metoo, we’ve finally knocked the fraudulent prefix, ‘post-’ off feminism. In this respect, it’s a great moment for activism, solidarity and consciousness raising, but it’s occurring in a context of increasing political polarization. Actions informed by far right ideologies sometimes prompt essentialist counter arguments on the left. I think we need to take our cue from women of color here, those who are insisting on an ‘intersectional feminism’, which would include, but not be limited to, the issue of sexual harassment.

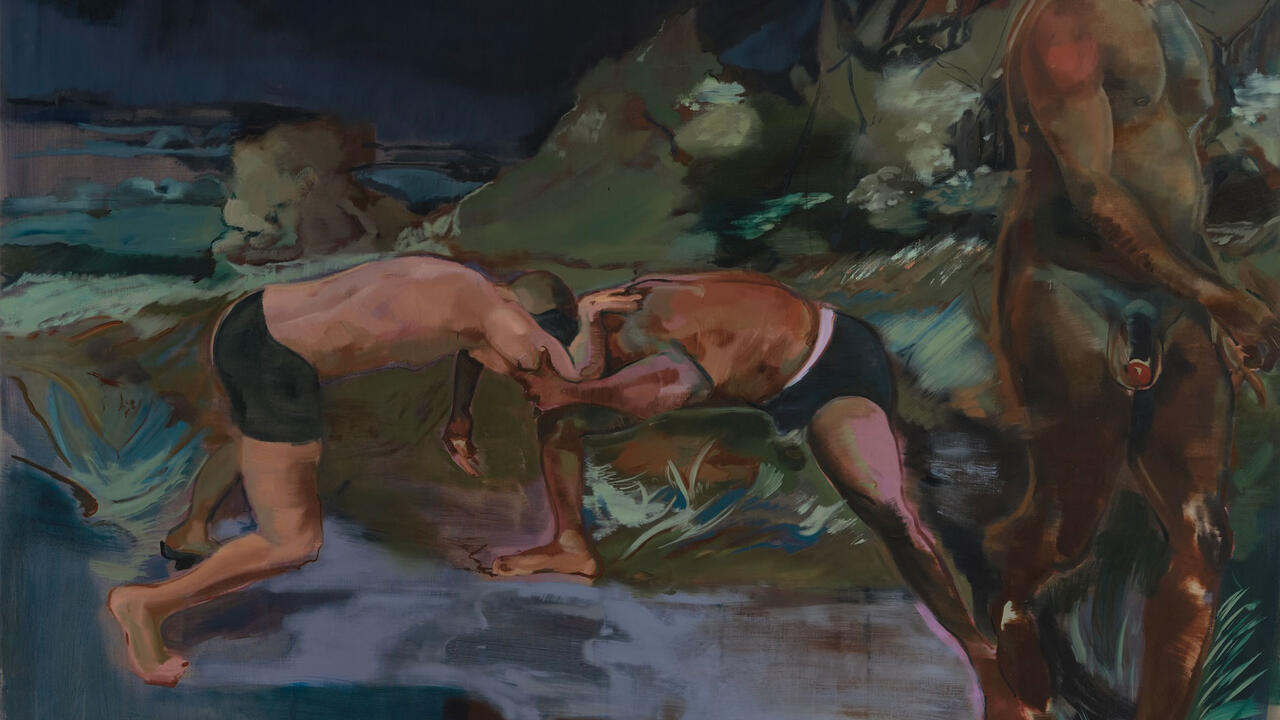

Mary Kelly’s work will be on view at Frieze London (4-7 October) with Pippy Houldsworth gallery as part of the themed section ‘Social Work’, highlighting the practice of eight women artists whose work emerged in response to the global social and political upheavals of the 1980s and ’90s.

Main image: Aasa Lunden, Portrait of Mary Kelly, 2018. Courtesy: the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London.