Barbara Bloom Goes Through the Looking Glass

The artist discusses her use of mirrors and their ‘destabilizing’ effects

The artist discusses her use of mirrors and their ‘destabilizing’ effects

Evan Moffitt: Mirrors recur throughout your work. What interests you about them?

Barbara Bloom: I’m constantly working in both two and three dimensions, back and forth. Mirrors are two-dimensional objects, but they reflect the third dimension. When a person looks at a mirror in an artwork, they see themselves looking at the work. I’m trying to call awareness to the active sense of looking.

EM: Is your understanding of active looking informed by modernism, which centres on the way artworks situate the viewer?

BB: I’m interested in worlds within worlds, references within references – Charlie Kaufman, Jorge Luis Borges. The first artists who interested me were those making phenomenological work about the nature of seeing, like Robert Irwin and Eric Orr. When you look at Irwin’s dot paintings and then look away, they leave an afterimage. I remember reading Lawrence Weschler’s description of painting as ‘blushing’ in Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees [1982] and thinking: ‘My God, that’s what I want to do!’ But I meant it in the psychological sense of your having such an intimate relationship with an artwork that you could make it blush by looking at it.

EM: Did that inspire The Reign of Narcissism [1989], your installation of a period museum dedicated to people – yourself included – looking at themselves?

BB: I set out to make something cringingly embarrassing after The Gaze [1986], in which viewers lifted up curtains to look at images. There was something very intimate and prurient about that. In the mid-to-late 1980s, I started thinking about artists who were known for their runaway egos, and I had just been to Italy, where I’d seen cameo portraits, which I loved.

EM: You made The Reign of Narcissism at the tail-end of a decade dominated, in the US, by a celebrity huckster president. It seems like a critical reflection on a cultural moment that has now returned in full force.

BB: Yes, absolutely – although no one could have predicted the infinite regress of where we were headed. I don’t think I could make that work now, because I wouldn’t feel comfortable reproducing its level of irony. I still find it haute creepy.

EM: Oftentimes, when you use mirrors, they’re partially occluded or pitched at odd angles, bringing a degree of instability to the spaces in which they’re installed.

BB: I try to make beautiful things that include some element of confusion. The artist David Salle once described me as a cruel hostess: I make people feel comfortable, but then I do all kinds of destabilizing things to them. This is also true of surrealism and the novels of Haruki Murakami; the membrane between parallel realities is so porous.

EM: The Rendering (HxWxD), your 2018 installation at the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Oberlin, didn’t incorporate any actual mirrors, but you treated artworks from the museum’s collection like mirrors, because the two-dimensional depictions of architecture within them were projected sculpturally into the gallery.

BB: I made that work in response to the museum’s 1977 extension, which was designed by Robert Venturi. It’s the most ridiculous, ego-driven Architecture with a capital A. The collection contains a number of works dealing with architecture: for instance, a beautiful 19th-century Indian print of a garden rendered in an impossibly complicated two dimensions. I wondered what would happen if these images of architectural space reverse-rendered themselves off the wall and into the space. In a way, this is the opposite of a mirror, which renders a three-dimensional object in two dimensions.

EM: Venturi’s building seems reverse-rendered. It looks much better on paper.

BB: It does!

EM: Can you tell me about your project for the Liberace Mansion in Las Vegas?

BB: As Dave Hickey wrote in Liberace: A Rhinestone as Big as the Ritz [2005]: ‘Bad taste is real taste, and good taste is the residue of someone else’s privilege.’ Las Vegas seemed like the perfect place to think about that. Most of Liberace’s original possessions are in his former homes in Palm Springs or Los Angeles, so the current owners of his Las Vegas house have been buying stuff that looks like it belongs there. Now, it’s a simulacrum of Liberace’s taste.

I discovered that there had been a piano-shaped pool in the backyard. The area now houses an events space featuring a copy of Liberace’s mirrored piano. I thought if I put three black baby grand pianos behind this star piano, like backup singers, they’d stand in for all the famous Las Vegas acts, like Gladys Knight & The Pips or Smokey Robinson & The Miracles.

EM: Behind the candelabra, as it were. You’ve used mirrors and images of celebrities in other recent works, like Joan Crawford in Vanity [2017]. Does the mirror in that work flatten the star into a sign, or does it offer us a greater sense of her vulnerability?

BB: The Eve Arnold photograph of Crawford that I used in Vanity is a depiction of what it means to concentrate on something. Crawford has her hand on her head, and she’s looking in a compact mirror. That’s the crux of the photograph. It’s like Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker [1880], with his fist on his chin. I used a vanity mirror as a framing device, working again with two and three dimensions: the sculptural and the flat surface. These works are primers on how I read an image.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 216 with the headline ‘Infinite Regress’.

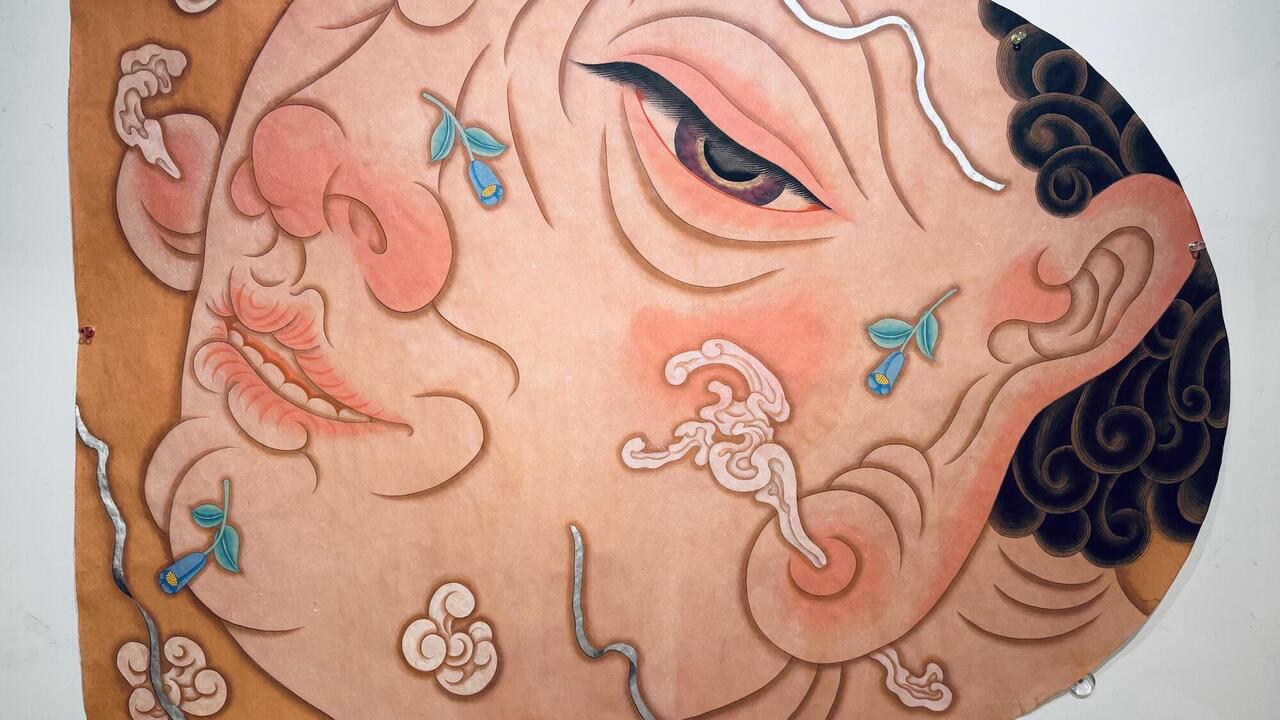

Main image: Barbara Bloom, Envy, 1987/2018. Courtesy: the artist and David Lewis Gallery, New York