After Kathy Acker

Chris Kraus’s biography of the first female ‘Great Writer as Countercultural Hero’

Chris Kraus’s biography of the first female ‘Great Writer as Countercultural Hero’

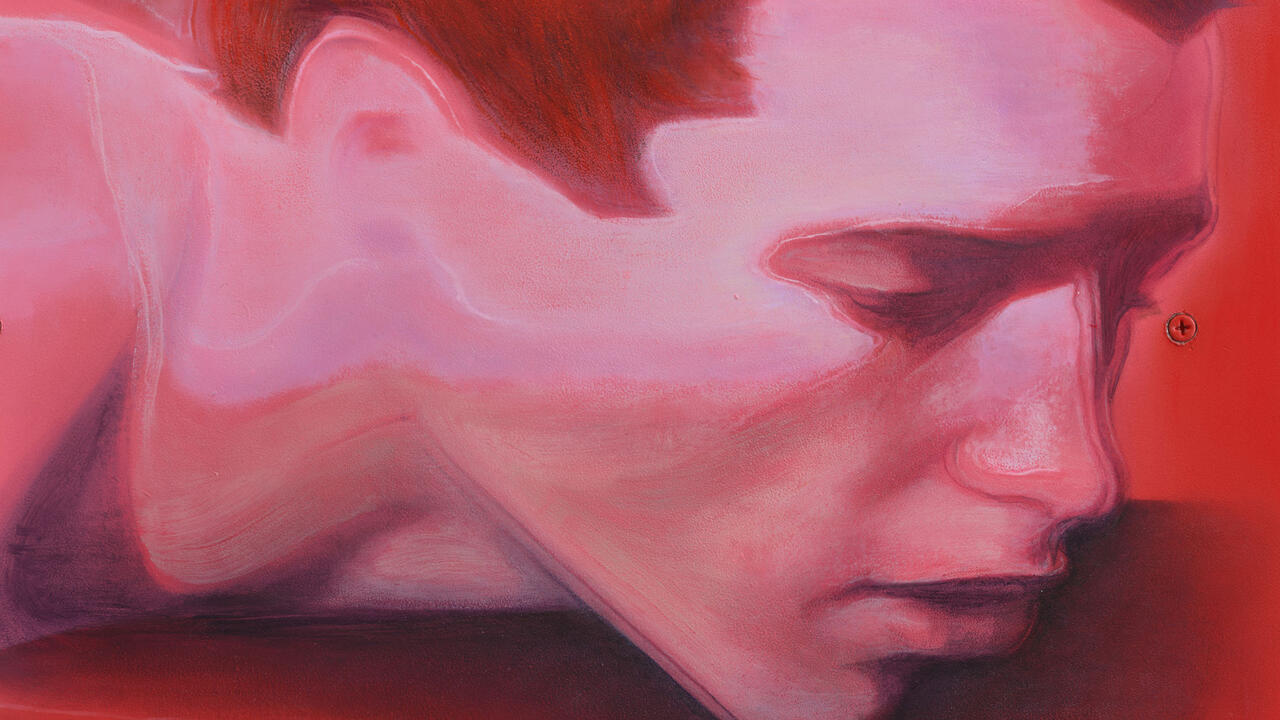

‘Perceptive readers of Acker’s work have observed that the lies aren’t literal lies, but more a system of magical thought,’ suggests Chris Kraus in After Kathy Acker, which seeks to reassess the myths around Acker’s life, and the merits of the writing that these myths have clouded. That this book will be sensitive and sympathetic to its subject’s combination of ‘rigorous honesty and self-serving white lies’ – sent in (critical) solidarity from one author who blurred the boundaries between fiction and memoir to another – soon becomes clear: ‘Didn’t [Acker] do what all writers must do? Create a position from which to write?’

The positives and negatives of becoming a legend – especially before death – is a key theme here, founded upon Kraus’ gentle reflections on the impossibility of accurate biography. Not only was Acker’s life turbulent, so were her times, and (transient) places. Few artistic milieus, perhaps barring inter-war Paris and Berlin, have been as mythologized as New York’s after the city averted bankruptcy in 1975: a paragraph alone on 1978 references Vivienne Dick, Lydia Lunch, Brian Eno, David Wojnarowicz, The Wooster Group, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Patti Smith. Kraus attempts to grasp how Acker perceived herself, and was perceived in this world of outsiders, having spent her youth negotiating New York’s complex Jewish immigrant hierarchies, feeling neglected at home and insufficiently recognized at high school.

These youthful frustrations grew first into a desire to build experimental narratives in every part of her life – Kraus highlights Acker’s time as a stripper, creating ‘audaciously digressive’ semi-improvised scripts – coupled with a lifelong search for stimulating intellectual circles and lovers. Kraus is deft at showing how these elusive quests, and the diverse range of influences they engendered, informed Acker’s practice: ‘It seemed to her that she, like most of her friends, had many shifting identities – or maybe none. Likewise, the idea of inventing a plot and creating relatable characters seemed absurd’. Inspired by her friend Eleanor Antin, as well as punk rock iconoclasm, Acker replaced such demands with her ‘appropriation’ technique, openly plagiarist, working ‘found’ text into searing, scathing prose that – for a while, at least – felt startlingly original.

It is no surprise to discover Acker’s contempt for ‘literary fiction’, nor her corresponding anxieties about getting ‘stuck in the ghetto of “experimental” writing’. Acquaintances struggled to reconcile their modernist-influenced ideas with their love of rock and roll, or felt analogous tensions between ‘high’ and ‘popular’ culture. Meanwhile, Acker saw form as a liberating force: her interests in art, sex, philosophy, music and literature could achieve unity via an overarching compositional strategy. Working around the well-established ‘form’ and ‘content’ divide, Kraus distinguishes between this technique and a search for a ‘voice’, instead focusing on Acker’s diaries as an amorphous space where she could evolve her style, develop her ideas, record thoughts and feelings, and grow into the first female ‘Great Writer as Countercultural Hero’. Having never done a full-time job and fetishizing a workmanlike approach, Acker’s determination to write every day became her main strength and weakness, helping her to create a striking style (and keep her in the minds of influential New Yorkers) but not allowing herself the time and space to move beyond it.

Kraus is generous about the flaws in Acker’s earlier works, allowing one of Acker’s friends or a quote from the author to explain them. Kraus reserves the most enthusiasm not for Acker’s breakthrough novel Blood and Guts in High School (1978) but its follow-up: Great Expectations, written in 1979–80 in response to her grandmother’s death and her mother’s suicide, which ‘at once summarises artistic experiments of the past twenty years and announces a changing of guard’. Kraus’ shift from this grandiose claim to a micro-focus on the evolution of Acker’s prose is sublime: she describes Acker’s use of the colon ‘as a slap, a jolt, an epinephrine shot that yanks the sentence – and by extension, us – from grief’s downward drift into the present’. This attention to detail springs, it seems, not just from Kraus’s affinity with Acker but their closeness (if not friendship) – the two women shared a lover, Sylvère Lotringer, and many mutual friends. At times, Kraus’s study prompts reflections on her own writing processes: I wanted more of these, but by treating such flights with caution, Kraus avoids the accusations of self-indulgence that hampered Acker’s later career, especially after her move to London.

By the 1990s, Acker had become a symbol of the previous decade’s excesses.

Kraus is most empathetic when dealing with Acker’s difficulties in writing after achieving an unprecedented level of magazine and television coverage, and then her decline and death. The exploration of sex in Acker’s writing and life became totalizing – she talked of trying to ‘write from the point of orgasm’ – making her a target for late second wave feminists opposed to pornography and BDSM, and contributing to disastrous reviews and her fall from grace within London’s ‘moribund and boring’ literary scene. By the 1990s, Acker had become a symbol of the previous decade’s excesses; her novels no longer seemed transgressive, instead clichéd and predictable, and a new generation of women writers, some of whom had been her friends, superseded her. ‘Nobody,’ Kraus notes damningly, ‘was talking about their tattoos’, before the heart-breaking detail that Serpent’s Tail told Stewart Home not to use Acker to blurb his novel (most likely Blow Job) as ‘Whatever she wrote would put people off’.

Was Acker behind her times, or ahead of them? Shortly before her death from cancer in November 1997, aged 53, Acker was happiest collaborating with bands (The Mekons and Tribe 8) rather than writing alone – a practice that brought together people who bought books with those who bought records, as well as uniting those who made them. Kraus suggests that Acker’s rehabilitation could have sprung from her interest in the internet and CD-ROM technology – used brilliantly by Chris Marker but none of Acker’s British literary peers, who seldom tried working in film, let alone digital media. (A parallel underground-overground British cultural figure is hard to find: I could only think of Derek Jarman, considered almost exclusively as a filmmaker.) Incisive reflections such as these raise After Kathy Acker to the level of Jonathan Coe’s Like a Fiery Elephant: The Story of B. S. Johnson (2004), which remains a benchmark for ‘experimental’ literary biography; Kraus intelligently brings together the myths around Acker, and then breaks them apart, offering us the tantalizing prospect not just of Acker’s unrealized digital redemption, but a proper reckoning with what she left in her wake.

Chris Kraus’s After Kathy Acker, A Biography is published 31 August 2017 by Allen Lane.

Main image: Kathy Acker at the gym, 1984. Photograph: Steve Pyke/Getty Images