Ajamu on the Pleasures of the Darkroom

In his home studio the artist explores pleasure, privilege and how ‘through our body, we bring our archives’

In his home studio the artist explores pleasure, privilege and how ‘through our body, we bring our archives’

Ajamu is many things: photographer, archivist, sex activist, filmmaker, elder, Trekkie. Since the 1980s, he has sought to use sensuality and desire as methods to play with fixed notions of the self and bounded understandings of the body. ‘If people come and think Ajamu’s work is simply about identity and representation,’ he reflected in his studio in Brixton, south London, ‘then they haven’t engaged with it.’ ‘The work of Black and brown artists often gets locked down into a discussion of social and cultural identity,’ he continued. The artist uses sensation and sex to bypass these conversations, drawing on the history and process of photography to explore ‘what I want to do and what I want to have done to my Black body’.

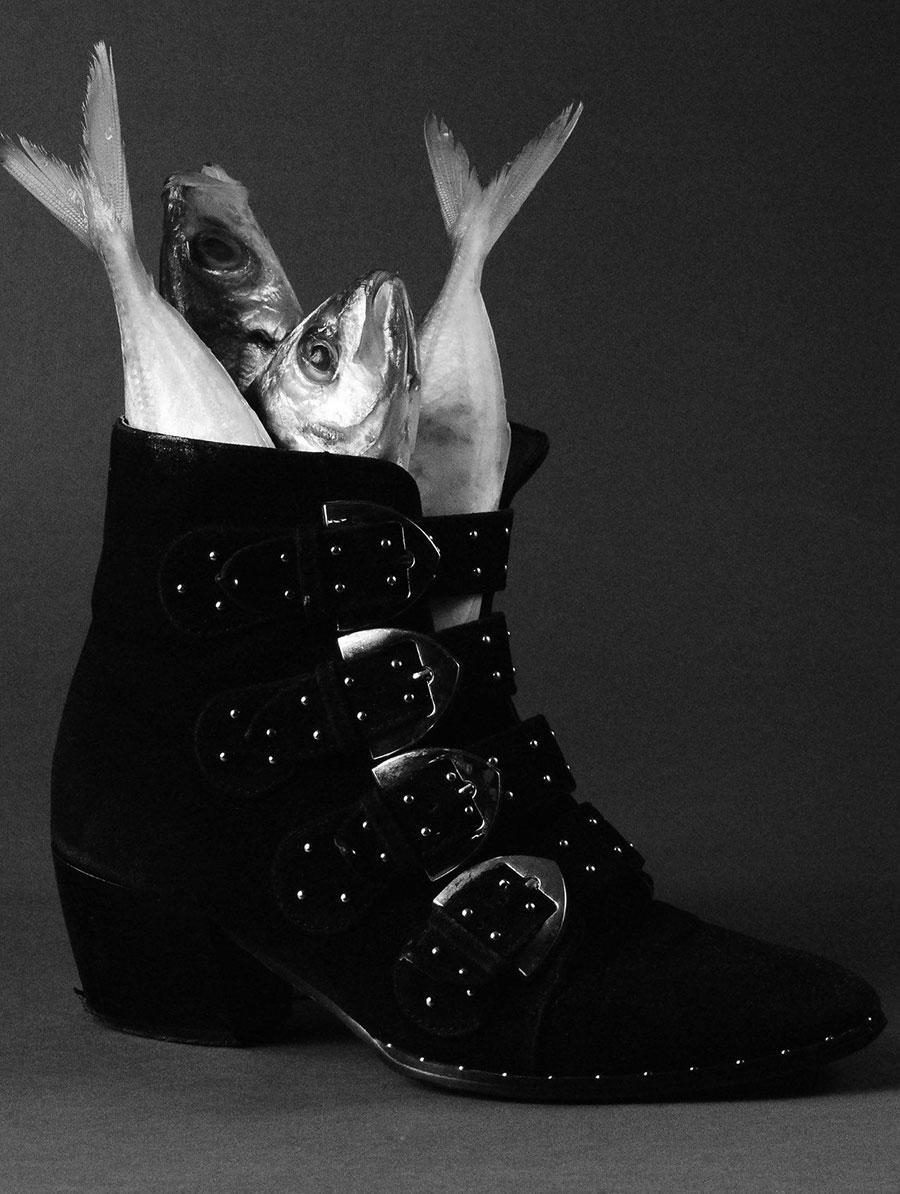

Ajamu was born in the northern town of Huddersfield in 1963, to parents who moved to Britain from Jamaica in 1961. He adopted the name Ajamu, which means ‘he who fights for what he believes’ in Yoruba, in 1991. Malcolm X was his first role model and his revolutionary politics informed BLAC (Black Liberation Activist Core), the magazine Ajamu co-founded in Huddersfield in 1985. Ajamu studied photography at first, in part, to fill its pages, before beginning the studio portraiture of Black and brown queer men that remains at the centre of his practice today. Always shot in black and white, his portraits also illuminate the objects his sitters use to incite their desire: the pointed shoes squeezed on under muscled calves in Heels (1993) or the leather harnesses, whips and thrones in the series ‘Circus Master’ (1997–98).

Photographs like Cock and Glove (1993) – a close-up black and white shot of a lace-gloved hand holding an erect penis – were central to discussions of photography and desire in 1990s Britain. In The Homecoming: A Short Film about Ajamu (1995), the works draw the reflections of Sonia Boyce, Stuart Hall and Kobena Mercer. That such leading figures were commenting on Ajamu’s work so early in his career is testimony to the instant impact it had on Black British art. Yet, as its title suggests, the film also attests to the importance of home in Ajamu’s work. It follows the artist on a journey from London to visit his mother in Huddersfield, where he is having his first institutional solo show. On the way to Brixton station, Ajamu passes both the former home of Rotimi Fani-Kayode – the late Nigerian British photographer whose images of queer Black men are a kind of preface to Ajamu’s own – and that of the Trinidadian intellectual C.L.R. James, in the same building that housed the radical magazine Race Today (1969–88). The Homecoming shows the different spaces – a flat shared with his lover, the streets of Brixton, his mother’s sitting room – in which Ajamu’s sexuality was not just accepted, but celebrated.

On my way to Ajamu’s home and studio, I cycled down a long, straight road and passed a sequence of small estates named after writers: Langston Hughes, James Joyce, Pablo Neruda, Alice Walker. It was one of those quietly surreal streetscapes London so often reveals, evoking Brixton’s history, clinging on in the face of gentrification, as a hub of Black global modernity. Ajamu’s home, where he has lived and worked for 20 years, also evokes this uncanny sense that layers of experience are hidden beneath the urban surface. Outside, it is a bay-windowed Victorian terraced house on one of the yellow-brick streets that sprawl across south London. Inside, the bay windows are blocked with a screen – the backdrop against which the artist takes his portraits of men in wigs and diamond collars, reclining on day beds in high-heeled shoes.

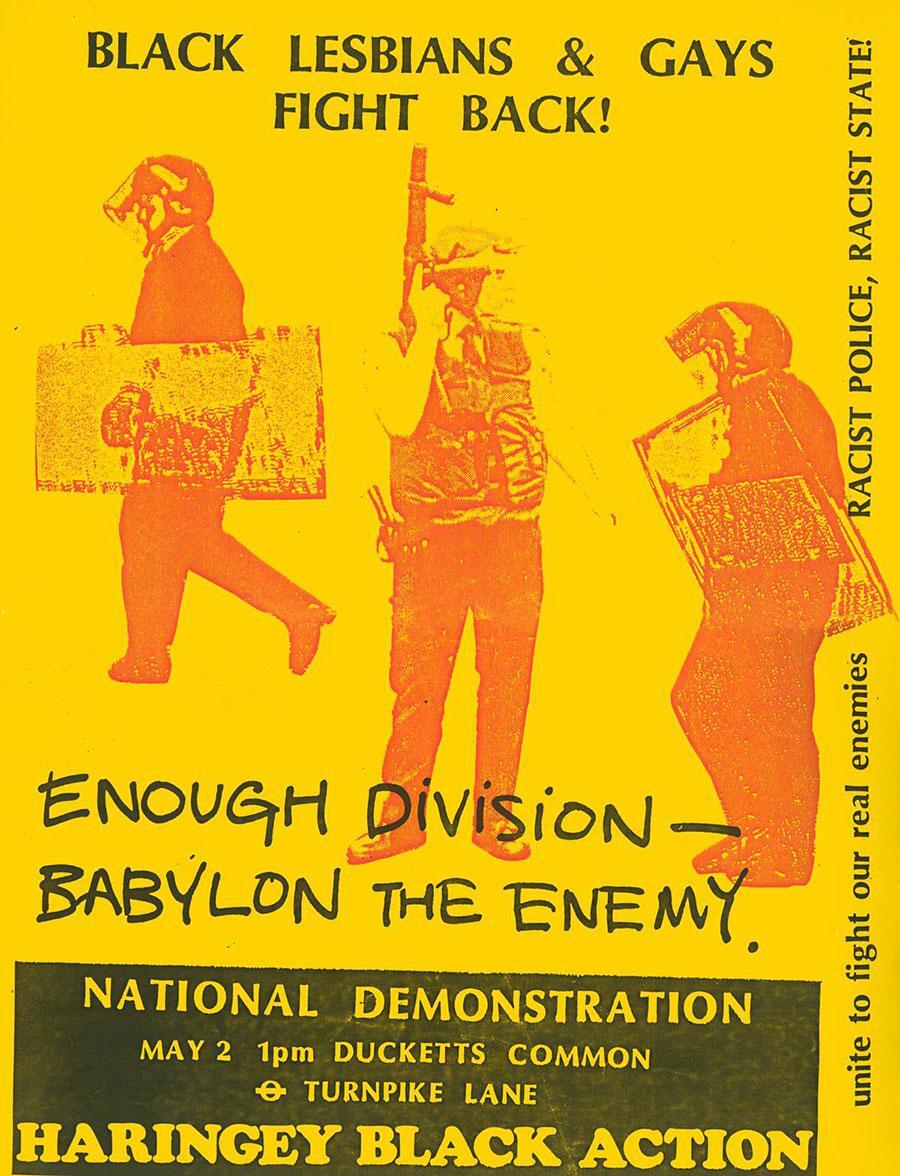

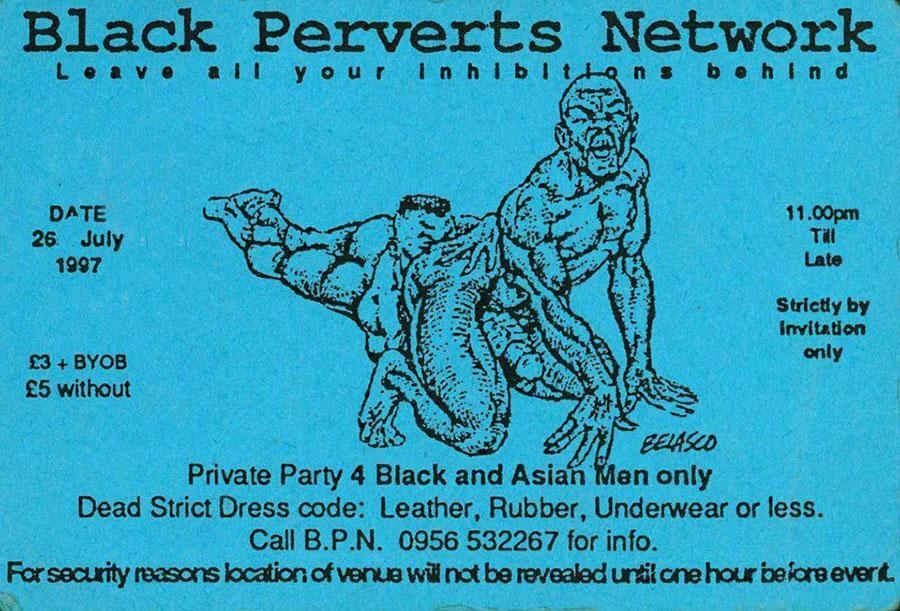

Ajamu’s front room, lined floor to ceiling with a library of photography and philosophy books, is also where the private sex parties of the Black Perverts Network took place in the mid-1990s. These were, in part, born from frustration: in predominantly white gay clubs in the early ’90s, he explained, Black and brown men would end up clustered together in a corner. In the US, parties like Black Jack in Los Angeles or Jacks of Color in New York had restrictive door policies: ‘It was basically no fats, no femmes.’ The Black Perverts Network was intended as a space for Black and Asian men to explore their desires away from both white racism and gay men’s body fascism. While continuing to build his archive of portraits, in 2005 Ajamu co-founded (with Topher Campbell, who directed The Homecoming) rukus!, the first archive of Black British LGBT life and culture. His sex parties were also informed by an archival impulse: they were a way to explore the body as a record not just of pain and trauma, but of pleasure. Through our bodies, as Ajamu puts it: ‘We bring our archives with us.’

Downstairs, in the basement bathroom, is a second space that is key to Ajamu’s work: the darkroom. Like the library-cum-studio, which brings together two kinds of archiving, this is a space that is used for two purposes in order to explore how they overlap. His darkroom is where he develops his photographs; it is also where, in the dim, red light, he has sex. There is a particular affect that comes with analogue photography, Ajamu elaborated: you are working in the dark; you don’t know what the images you have taken will look like; you enter a state of anticipation. Above all, you have to wait. So, too, with the texture of eroticism that comes with sex in a darkroom. ‘It teaches you the pleasure of waiting and that maybe waiting, and nothing happening, can be enough. In a darkroom, it’s like that line in Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments [1977]: “I am the one who waits.”’ In the dark, other connections between photography and sex emerge: ‘Poppers smell like photographic fixer. Did you know that?’

Ajamu works almost exclusively in analogue: his interest lies in the materiality of photography and photography’s relationship to other material forms, above all the body. Yet, the hegemony of digital technology has caused printers and studio darkrooms to close down, threatening a loss of skills and practical knowledge. I can’t help but think that digital technology has caused the other kind of darkroom to disappear, too, as sex apps, with their carefully pre-selected encounters, have led to less demand for the dim spaces of backrooms and dungeons in gay bars and at sex parties, and the archives of unexpected pleasures they contain.

The darkroom forces attention on the photographic process as embodied, intimate and time-bound. It also draws attention to senses beyond vision: the feel of prints, the smell of chemicals. This is the focus of Ajamu’s current research, as a PhD candidate at London’s Royal College of Art: how can the photographic archive reveal how we understand the world through senses other than vision? In European philosophy, from Plato down through René Descartes and John Locke, sight sits atop the hierarchy of the senses, associated with knowledge, rationality – and whiteness. Touch, smell and taste are considered the lower senses, and their ascription to Black and brown bodies is core to the process of racialization. Indeed, ‘race’ is produced through what Irene Tucker terms, in her eponymous 2012 book, ‘the moment of racial sight’: looking turns bodies into vehicles of social identity.

For Ajamu, emphasizing the non-visual aspects of photography – working in and with the dark, in all senses of that word – enables a ‘move from the social body to the material body’. That is to say, it allows him to ‘refuse to see the body in terms of representation’, but rather in terms of sensation – as something open, leaky. (‘Skin is porous.’) One way to view some of his best-known photographs – such as Bodybuilder with Bra (1990), a cropped image of muscular shoulders bound within a white bra – is as representations of a certain kind of Black sexuality; another is to note how carefully skin is lit and shot in many of his images, revealing pores, hair, sweat – the material traces of our bodies’ interactions with the world.

Back in Ajamu’s front room, test photographs from his current work in progress lie on a side table: a series of black and white images of medical speculums, shot close up, so that their metal curves resemble the folds of a vulva or the opening of an anus. These images seem to mark a drastic shift: for almost the first time in decades, they eschew the human body. Yet, these are objects of a particular kind: like the chastity cage studded with metal spikes that lies beside the photographs, these instruments enable pain as well as pleasure; they decide the boundary between them. For Ajamu, these photographs are investigations into how we can ‘think about pleasure in a way that doesn’t privilege the human’. He has long been influenced by Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye (1928), a novel in which the narrator pursues increasingly frenzied and necrophiliac impulses by penetrating his lovers with a sequence of objects – eyes, testicles, eggs. Living or dead, human or non-human: it turns out that any soft, round object can produce the same effect. The all-seeing eye is debased into just another thing to be touched.

In showing how desire blurs the division between human and object, person and device, Ajamu’s new works draw on a long tradition of dissident surrealist photography – from Hans Bellmer’s dismembered dolls to Pierre Molinier’s photographs of custom-made erotic objects (including a pair of dildo shoes, which he used to fuck himself). As in other surrealist iconographies – Man Ray’s Le Violin d’Ingres (1924); Claude Cahun’s photographs of strange, doll-like figures under bell jars (‘Untitled’, 1936) – objects come to resemble the bodies they force open, for pleasure as well as pain. This new series also realizes Ajamu’s intention to move beyond the concern with representation, identity and objectification present in his earlier work, as well as in that of photographers like Fani-Kayode or Lyle Ashton Harris. These photographs eschew a representation of the Black body in pursuit of the objects of Black desire.

Largely confined to his studio while the UK was in lockdown, Ajamu has been working to establish an online Black queer photographers’ salon. This is an extension, in virtual space, of the mentoring he has long undertaken, opening his library, darkroom and studio space to younger Black queer photographers, including Irvine Bartlett, Terrence Burford-Phearse, Cameron Ugbodu and Matthew Arthur Williams – artists he intends to photograph for his upcoming show at Cubitt in London. He wants his home to continue to act as a space outside the art-school system in which younger Black queer artists can learn that ‘you don’t have to produce a certain kind of “art” and you don’t need validation from certain kinds of institutions’.

There is something overdetermined, in the best kind of way, about Ajamu’s house: for 20 years, it has been at once a studio, darkroom, sex club, fugitive school and research library. It seems to me that the key to his work is that everything happens in the same space: the home as an archive of feeling, loving or just living. When I point this out to him, he reflects: ‘Photography, archiving, sex, my studio – it’s all a form of world-making; I’m trying to create a world.’

This article first appeared in frieze issue 216 with the headline ‘Ajamu: The Pleasures of the Darkroom’.

Ajamu is a photographer, archivist, radical sex activist and co-founder of the charity rukus! Federation and the rukus! Black Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer Archive. His solo show ‘Archival Sensoria’, curated by Languid Hands, is on view at Cubitt, London, UK, from 10 February to 4 April. A limited-edition artist book, Ajamu: Archive, will be launched during the exhibition. His work will be included in Glasgow International, UK, from 11 to 27 June. He lives in London.

Main image: Ajamu, from the series ‘Circus Master’, 1997, photograph. Courtesy: the artist