The Alchemy of Nicolas Roeg (1928–2018)

‘Cinematic’ is often overused, but Roeg’s films showed how minds and memories wander back and forth in time, colouring our experience of the world

‘Cinematic’ is often overused, but Roeg’s films showed how minds and memories wander back and forth in time, colouring our experience of the world

Art Garfunkel said that director Nicolas Roeg, who died last week at the age of 90, ‘brought me to the edge of madness and violence’ when he starred in Bad Timing (1980). David Bowie, speaking about his experience working with Roeg on The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), called him ‘an old warlock.’ ‘There is a very strong alchemy in his movies,’ the musician explained. ‘They are magical. You come out winded from the experience of working with him.’

Bowie was right: there was something of the supernatural and mystical to all of Roeg’s films. Formally, he teleported his audiences through time using complex cross-cutting techniques in the editing room. In Don’t Look Now (1973), Roeg repeatedly switches between images of a couple having sex and getting dressed afterwards. Bowie’s alien Thomas Jerome Newton sees an apparition of the 1930s dustbowl whilst driving across ’70s America in The Man Who Fell to Earth. David Gulpilil, who plays the unnamed indigenous teenager in Walkabout (1971), has a vision of turn-of-the-century British colonialists crossing the Australian outback by camel. Roeg’s friend, director Bernard Rose, has argued that he would ‘connect the shots on a psychic basis’ as a way to plant narrative clues. These co-existent passages of time gave his stories a psychological depth, as if in search of a truth about the discontinuities of memory and perception.

Roeg’s characters are otherworldly, literally so in the haunting and sad The Man Who Fell to Earth, a film which uses science fiction to speak about loneliness, alienation and what it means to belong. They shape-shift – most notoriously in the dissolution of gender and class that occurs between Michele Breton, James Fox, Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg in Performance (1970), or the occult masquerades in his delightful 1990 adaptation of Roald Dahl’s children’s novel The Witches (1983). His films observe rites of passage and cycles of birth and death. Think of Jenny Agutter and Gulpilil, both coming of age in different ways in Walkabout (1971). Think of Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as grieving parents visiting a wintry Venice, haunted by the death of their daughter in Don’t Look Now. The movie’s now famous bedroom scene between Sutherland and Christie captures the intimacy of a married couple who know each other profoundly, who have seen the giddy heights of love and plunged into the bleak misery of bereavement. It is a film bookended by deaths, but ends with the promise of new life, as Christie discovers she is pregnant. Eureka (1983), which makes use of Vodou imagery, is a cautionary tale about materialism, nature and violence. Wealth brings only death and misery to Gene Hackman’s gold prospector. Sorcery makes itself explicit in Roeg’s final feature made in 2007 – an adaptation of Fay Weldon’s novel Puffball (1980) – in the form of potions and spells designed to bring about pregnancy.

According to Rose, Roeg once found himself in an argument with fellow British director Alan Parker, who boasted that his working class London background gave him some form of automatic integrity. Roeg reportedly said: ‘Alan, you were never a workman, you went straight from art school into an advertising agency. I was a workman, I used to carry the cases up the hill.’ With his reputation as an auteur, built on his first quintet of films Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell), Walkabout, Don’t Look Now, The Man Who Fell to Earth and Bad Timing, it was easy to forget that Roeg had served two decades as a cinematographer working for other filmmakers. After starting his career in the late 1940s at Marylebone Studios, London – first making tea, then as a clapper-loader – Roeg began to learn the cinematographer’s trade. He went on to shoot films for directors including David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia, 1962), Clive Donner (The Caretaker, 1963), Roger Corman (the sumptuously coloured The Masque of the Red Death in 1964), Francois Truffaut (Fahrenheit 451, 1966), John Schlesinger (Far From the Madding Crowd, 1967) and Richard Lester (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1966, and Petulia, 1968). He was the original cinematographer on Lean’s Dr Zhivago (1965), until he was fired and replaced with Freddie Young, who took all the glory. Arguably, Roeg’s career as a director began because Donald Cammell, who had hired him to shoot Performance, could not make the film alone.

Before its release, Performance ran into trouble with Warner Bros, who had been expecting a fun, Swinging London vehicle for The Rolling Stones and demanded extensive re-edits. When it finally came out, John Simon of The New York Times wrote, ‘You do not have to be a drug addict, pederast, sadomasochist or nitwit to enjoy Performance, but being one or more of those things would help.’ It was not the first Roeg feature to face controversy. The sex scene in Don’t Look Now – one that today is celebrated for its tenderness and clumsy naturalism, yet which both Sutherland and Christie found difficult to act – ran foul of censors both on its theatrical release and when it was first shown on British television. Bad Timing, a disturbing portrait of an obsessive, toxic relationship, features an upsetting scene involving Garfunkel raping a suicidal Theresa Russell. Famously, even the film’s distributors, Rank, described Bad Timing as ‘a sick film made by sick people for sick people.’ Both the actors and crew found the shoot gruelling. Interviewed in 2000, Roeg recalled that production ‘was claustrophobic – play the part, go to sleep, go back. I abandoned control, and something magical came in. Bad Timing began to live itself. I kept out of the way of its forcefield. It was a bit of suspended time. A parallel universe.’ (Roeg and Russell were married in 1982, two years after the film’s release.)

Roeg’s debut proper, Walkabout, which was released in 1971, the same year as the horror film Wake in Fright – itself an extraordinary depiction of rural Australian life, directed by the Canadian Ted Kotcheff – has now been adopted as an honorary Australian New Wave film. It launched the career of indigenous actor Gulpilil, who during an interview with Margaret Pomeranz at Melbourne’s Wheeler Centre in 2005, explained that he did not speak English at the time, relying on his brother-in-law to translate Roeg’s directions. Walkabout has been rightly acclaimed for its radical use of sound design and its minimal script – the screenplay was apparently only 14 pages long. Film critics have analyzed it for its frank depiction of adolescent sexuality and attempts to confront the legacy of colonialism in Australia, yet it’s also hard not to see it as reproducing the colonialist eye: a film made by a British director, featuring almost all British actors and funded by American money.

What sets Roeg apart from other British directors is the intense visual language of his films. The sparse dialogue and realist acting performances, sliced and sutured using hallucinatory editing, place emphasis on the image rather than the word to tell his stories. His work sits closer to that of Derek Jarman, Peter Greenaway, Andrea Arnold, Sally Potter, Steve McQueen and other British art house directors, than the storytelling of Lean, Lester, Schlesinger, and other directors he cut his teeth with. Roeg’s sensibility leapfrogged his films over the traps of literature and theatre that so much British cinema gets caught in – a tradition held in the thrall of British literary heritage. His films traced lines back to the silent film era, to the primacy of the picture. The word ‘cinematic’ is often overused, but Roeg’s work earns the term because his films sensitized audiences to the ways minds and memories wander back and forth in time, colouring our experience of the world. He understood that our sense of self is made from cross-cuts, splices, puzzling discontinuities and occasional magic.

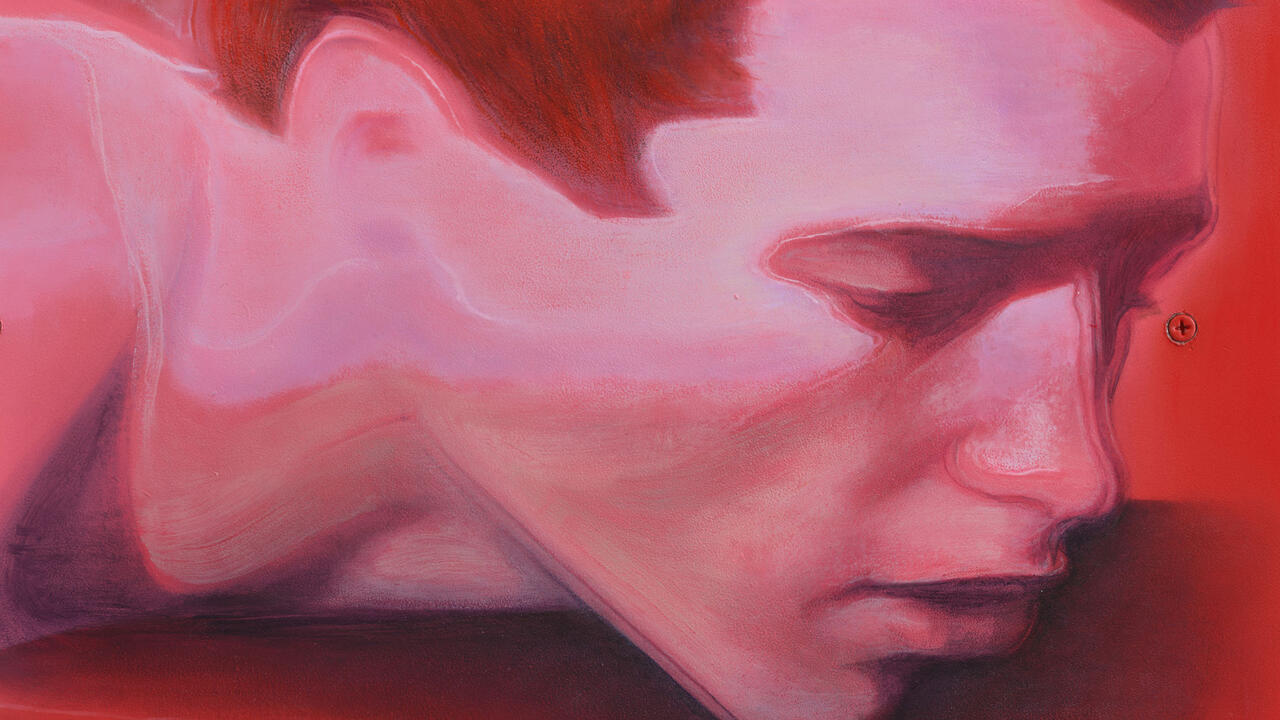

Main image: Nicolas Roeg on set. Courtesy: Faber & Faber