All The Best Shows

The winner of this year's Palme d'Or is a fictionalized portrait of contemporary culture's new villain: the curator

The winner of this year's Palme d'Or is a fictionalized portrait of contemporary culture's new villain: the curator

It would seem that curators have replaced bankers as the villains du jour. In a recent article, published in the German weekly Die Zeit, critic Stefan Heidenreich wrote that ‘curating is undemocratic, authoritarian, opaque and corruptible’. Heidenreich’s piece reflects not only the mixed critical reception of this year’s documenta 14 and 57th Venice Biennale but also the vicious campaign against Chris Dercon, which has been raging since April 2015, when the former director of London’s Tate Modern and Munich’s Haus der Kunst was announced as the next head of Berlin’s Volksbühne theatre. Back in May, there were a few soberly reasoned critiques of Dercon’s rather run-of-the-mill, contemporary-art-at-the-theatre programme that launched last month. But, over the summer, the outpouring of hatred on social media became increasingly frenzied: Dercon has received threatening letters and shit has been dumped on his doorstep.

It’s not entirely clear what has fuelled this resentment. It can’t simply be that Dercon is a white, heterosexual, alpha male – after all, many of his opponents are self-confessed admirers of his predecessor, Frank Castorf, who falls into the same category. It should also be noted that Castorf has received surprisingly little criticism for not allowing a single female theatre director of repute to flourish during his 25-year reign. Rather, Dercon seems to be perceived as a member of the neo-liberal, cosmopolitan art elite that is apparently hell-bent on gentrifying a stubbornly idiosyncratic local culture. Sure, some of his remarks smack of the kind of curator- and marketing-speak that makes sensitive souls wince. But the caricature is unfair; a lot of people I know who have worked with him describe Dercon as well-informed and patently collegial. So, why the vitriol? A Swedish film that won this year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes might provide an answer.

The opening scenes of Ruben Östlund’s The Square (2017) introduce us to the main character, Christian (Claes Bang), who is taking a nap on a Scandinavian modernist sofa. An assistant wakes the lanky, handsome, bespectacled, designer-suit-wearing museum director for a TV interview with American journalist Anne (Elisabeth Moss). They sit down in the pristine white cube gallery, between a neon work that declares ‘You have nothing’ and Wolfgang Laib-style heaps of dust on the floor. With feigned naivety, Anne asks Christian to explain a gobbledygook quote from a press release on the museum’s website. He responds with an awkward pause before wandering off topic, to which Anne responds with further pauses, as both eye each other flirtatiously. In the following sequence, we see the dismantling of an equestrian statue of King Carl John of Sweden in front of the Royal Palace in Stockholm, which has been turned into the contemporary art museum that Christian helms. The crane operator makes a mistake and beheads the statue, which collapses. The monument is replaced by a participatory art work, called The Square, which becomes the centre of a media scandal.

A few minutes into the film, all of the clichés are in place: the slick curator slouching on a designer sofa; the shallow, rip-off art works; the cryptic art-speak; the failure to respond candidly; the non-committal intimacy; the brutal doing-away with tradition, replaced by empty promises. Yet, Östlund’s film is more nuanced than it initially appears, and so is its central character. Christian tries to be a good person but fails because his position in the system demands that he behave opportunistically, especially when faced with a dilemma. The scandal produced by a promotional video for The Square puts him in a familiar media deadlock: if he cancels the campaign, he’s accused of censorship; if he continues with it, he’s morally irresponsible.

The Square makes achingly clear that curators have been increasingly enmeshed in a public showdown of the pretty versus the scandalous, the smoothly marketable versus the bathetically moralizing. The problem, however, is not that curators make subjective decisions instead of submitting to their audience’s majority opinion, as Heidenreich seems to suggest. Rather, it’s the other way round: there are simply too many strings attached to the job; too much politics, marketing and opinion polling, all of which echo the attention-grabbing logic of mainstream and social media. Given this, it’s inevitable that curators have become the scapegoats for society’s failure to confront its moral dilemmas. Perhaps it’s time for curators to opt out of the false choices, live with their bad reputations and just get on with it. If the devil has all the best tunes, curators should stage all the best shows.

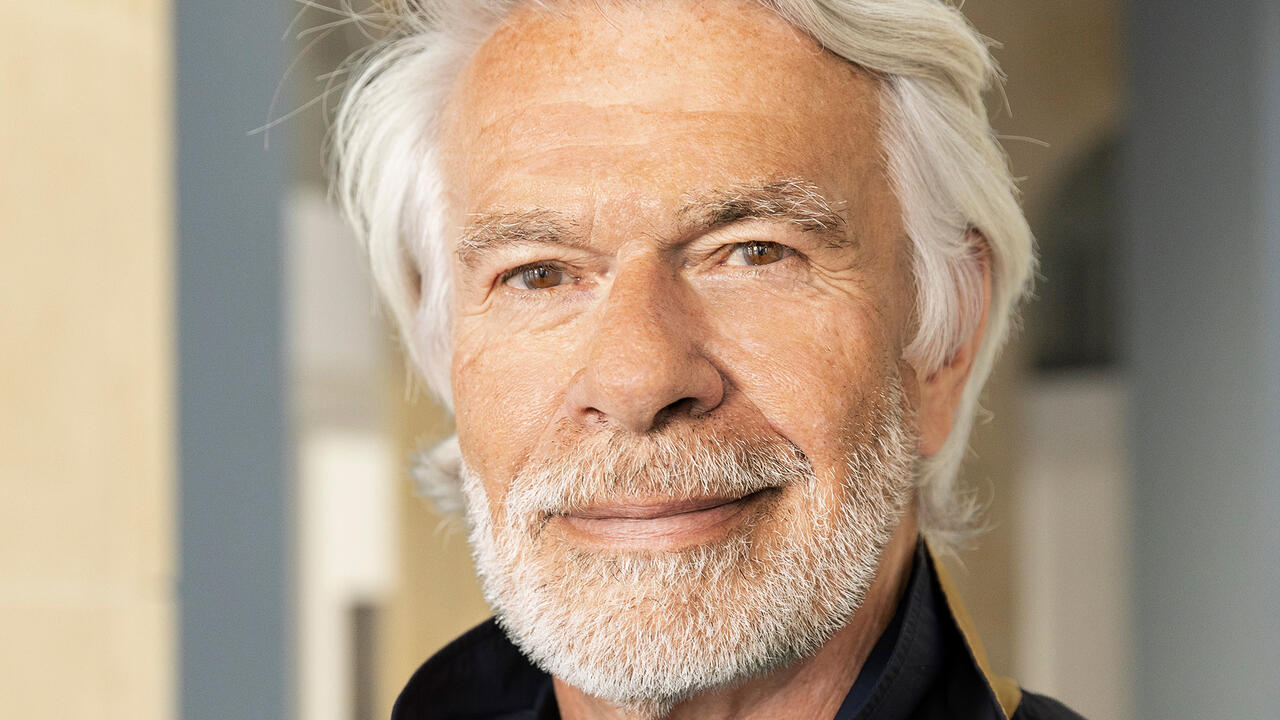

Main image: Ruben Östlund, The Square, 2017. Courtesy: Alamode Film