ANOHNI’s Music Speaks of Queer Resilience

After a seven-year hiatus, the artist returns this summer with a startling new album of ‘true feelings’

After a seven-year hiatus, the artist returns this summer with a startling new album of ‘true feelings’

I first heard ANOHNI after her second album, I Am a Bird Now (2005), was awarded the prestigious Mercury Prize – a first for an artist who sang openly of queer and trans desire. At the time, I was a teenager living in South Carolina, a conservative state in the midst of heated evangelical revival. A boy in my hometown had been beaten almost to death for flirting with the wrong jock and Congress was contemplating a constitutional ban on gay marriage. To be openly (or suspectedly) queer or trans meant living with a gun to your head, sometimes literally. You survived by entering a state of inner exile. A friend of mine played ‘Hope There’s Someone’ – the opening track of I Am a Bird Now – in his parents’ basement. At the first notes of the piano, against which ANOHNI pines for a love to ‘set my heart free’, we were entranced by a music profoundly resonant with our lives. She sang of longing and dysphoria, her voice conveying the melody of those feelings we were forbidden from saying aloud.

Last November, I met ANOHNI one afternoon at the non-profit art space Participant Inc., on Houston Street in New York. Born in Chichester, UK, ANOHNI was raised in Northern California, where her musical affinities began with the local Deathrock scene – a darkly pretty subgenre of punk. Violence against trans and queer bodies wasn’t uncommon in Northern California, though when she headed east, it was as much for the artists and community as it was to flee Reagan country. Today, ANOHNI is a commanding figure, her speaking voice as dolorous and passionate as when she sings, with only the faintest English accent. Her eyes are large, watchful.

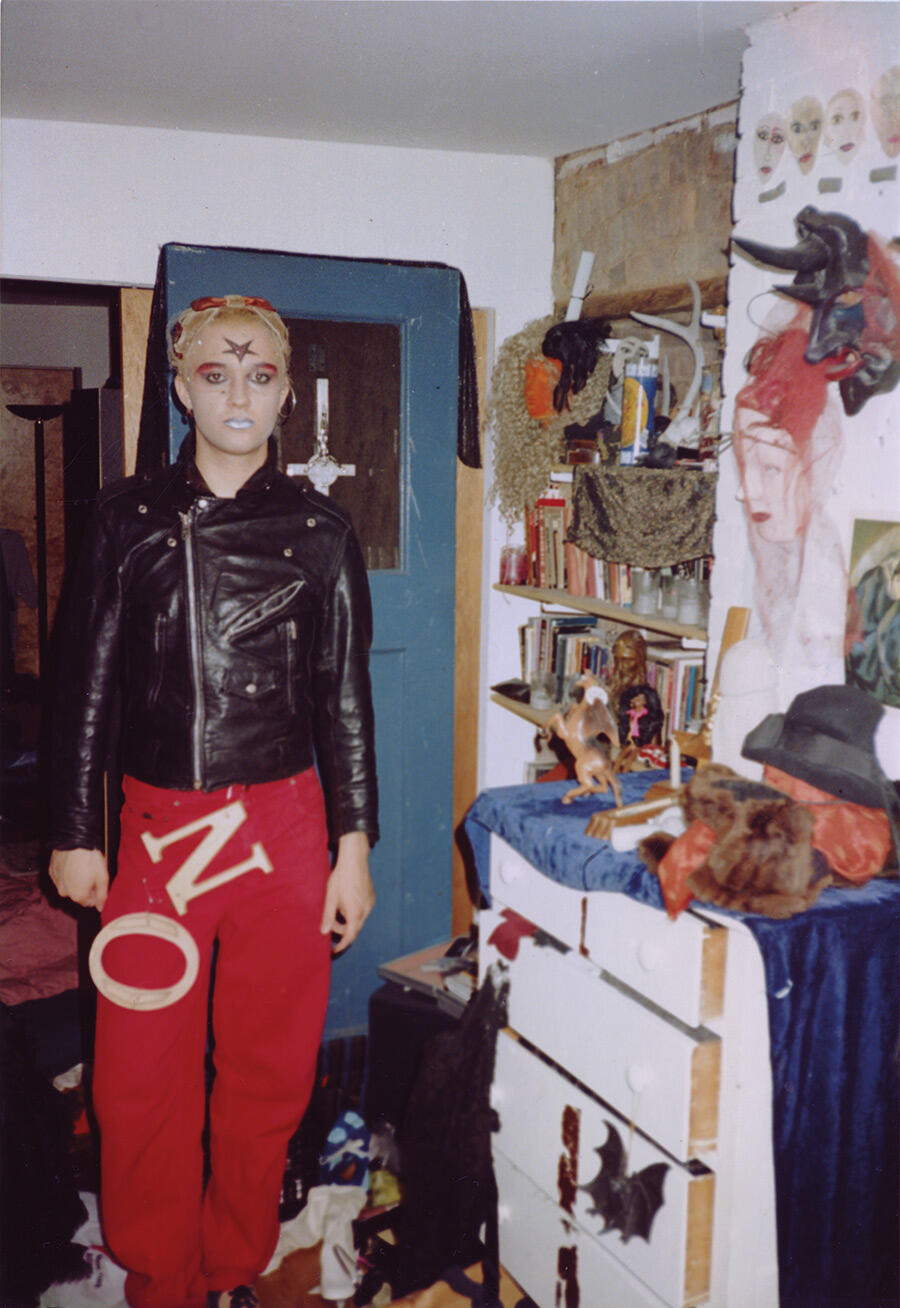

With Lia Gangitano, founder and director of Participant Inc., ANOHNI had organized ‘Blacklips Performance Cult: 13 Ways to Die’, the third in a series of exhibitions devoted to the eponymous, late-night theatrical collective ANOHNI founded with Johanna Constantine in 1992. (The group would disband three years later.) A ring of 29 televisions screened videos of Blacklips’s plays and musicals, all staged on Monday nights at the Pyramid Club in New York. Only one film was shown with sound per day, on a large screen in the middle of the room. Ranging from the lightly rehearsed to entirely ad hoc, Blacklips could be as irreverent as it was serious. They threw together stage sets from rubbish rescued off the streets, sometimes sewed their own costumes at home and drafted dialogue on the fly.

These heady and fantastic nights at the Pyramid first introduced downtown audiences to ANOHNI’s music, including her play The Birth of Anne Frank (1994), which she later adapted for Performance Space (formerly Performance Space 122) in 1995. Filmmaker Charles Atlas collaborated with her on a film version, though it was never completed. In one extant clip from 1994, shot by Atlas as a screen test, Blacklips member Page Reynolds croons ANOHNI’s ‘River of Sorrow’ (later released on her first album, Antony and the Johnsons, in 2000) while wearing cat’s-eye sunglasses against a bright red background. ‘Manhattan was a sanctuary,’ ANOHNI told me, when discussing the city of the early 1990s. ‘It was a place where visibly queer people could come from around the world to be safe and to find camaraderie.’ Still, it could also be dangerous, unforgiving. When I asked ANOHNI about Reynolds, she told me she had died in 2002 at 40. ‘That’s like 80. Trans queen years are double normal human years.’

The East Village of the 1980s and early ’90s, when ANOHNI landed in New York, was a graveyard. Death notices for people in their 30s, 40s and 50s filled the papers, and memorials were held almost daily – at St. Mark’s, at Judson Memorial Church, in homes, in parks. Blacklips was for young people and survivors, the sick, the barely-hanging-on. Once host to some of the city’s greatest performers of the downtown scene, the Pyramid was past its prime by ANOHNI’s arrival: many of the venue’s regular performers were dead, as was a sizable portion of its audience. ‘We were entering the era of drag queen-as-novelty-waitress and the old drag dynasties were collapsing,’ ANOHNI later told me, while we were sitting in her apartment, next to the piano where she composes. RuPaul’s surprise radio success with ‘Supermodel (You Better Work)’ in 1993 was more a puzzle than a promise. AIDS was still ravaging the city, especially artist communities; the streets were littered with signs of a violently departed world – paintings and photographs, clothing, furniture, keepsakes, all of it hauled to the curb by families, landlords and lovers unsure of what to do with the personal effects of the plague generation.

Around that time, ANOHNI found a discarded photograph by David Wojnarowicz on the pavement – this was the sort of detritus washing ashore in the Village. Wojnarowicz himself had died the year Blacklips was founded, as had Marsha P. Johnson, the legendary Black trans activist whose life and work profoundly shaped ANOHNI – and from whom her band borrowed its name. ‘Hibiscus [the American performer of the 1960s and ’70s] dreamed of an ecstatic, spectral, hallucinatory, effeminate theatre where Jesus was a girl,’ ANOHNI said. ‘Marsha was the living embodiment of that idea.’ When the two met at Gay Pride in 1992, ANOHNI kissed Johnson’s hand, six days before she was found dead by the Hudson River. (Her death, scarcely investigated by the police, was officially ruled a suicide.)

At Participant Inc., signs of that lost world mingled with its survivors. Flloyd – an original Blacklips performer – arrived the day I visited to watch some of the films in which he’d starred. One of his plays, Death! (1994), had captured my attention: Nameless Boy Prostitute lies in hospice care, dying of AIDS, confronted by Death (described in the script as ‘a horny, snotty-nosed demon with pus dripping from its Barbed Prick that you can’t wait to taste’). One of the final performances the collective staged, it played soundlessly on a wall-mounted television. So seriously was the play treated by the collective that posters billed it pre-emptively (and winkingly) as a ‘masterpiece’.

This July, almost 30 years since the end of Blacklips, ANOHNI will release My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross. It opens with the six-minute ‘It Must Change’, a soulful, downtempo rendition of a protest song that might have been sung by Sam Cooke; it is especially personal, when compared to the political rage of her last album, HOPELESSNESS (2016). ‘That [record] was just me in full war mode,’ she told me at her apartment. ‘But this [new] record is very much about what’s happened in my life – all my true feelings.’ Throughout the new LP, ANOHNI is accompanied by individual instruments, a lone guitar. Such intimacy etches within greater political terrain small, protective chalk circles for you and her to stand in. On ‘Scapegoat’, she sings: ‘You’re so killable / just so killable / It’s not personal / It’s just the way you were born.’ She can be startlingly raw, as in the lullaby-like ‘There Wasn’t Enough’, her voice straining as she half whispers of ‘hungry hearts for hungry hands’.

ANOHNI is reticent about performing this album of ‘true feelings’ live; the stage can be an uncomfortable place. She still speaks with a hint of the old war-mode: ‘Artists are told to compartmentalize this barrage of conflicting intentions directed towards them. Some will try to convince you that media representations of you are not relevant. But it can’t be honestly managed without sophisticated self-defence or an inevitable deadening of the work.’ The songs of My Back yearn for life, fragile life, and they insist on your aliveness, too.

When I spoke to the composer William Basinski – he produced ANOHNI’s first demo, played in her band and hosted her first solo concerts at Arcadia, the Williamsburg loft/venue he shared with his partner, the painter and curator James Elaine – I asked what he thought about My Back. His eyes widened. Its range left him almost at a loss for words. ‘You know her voice,’ he said, in his distinct Texan drawl. That was praise enough.

As musicians and artists, Basinski and Elaine had nurtured and mentored ANOHNI since she was part of Blacklips. ANOHNI would travel across the river, from her small room in Manhattan to Arcadia with its ‘tripped out baroque antique glamour that we restored from a pigeon ruin’, Basinski remembered. When Basinski completed The Disintegration Loops (2002–03), his four-part masterpiece of contemporary American music, the first person he called was ANOHNI. While listening to records and talking art, ANOHNI admired Elaine’s sculpture and painting, which decorated the vast walls and floors of Arcadia.

ANOHNI was mesmerized by a series of Elaine’s drawings that were created by pressing roadkill and other dead animals into renaissance art catalogues – a moving effort to exalt these small, forgotten creatures. Here was an art consonant with ANOHNI’s music, preserving from wretchedness a lasting emblem of dying beauty. ‘Nothing in art is broken,’ Elaine explained to me when we spoke over Zoom, recalling ANOHNI’s fascination with the series, ‘but, outside of that, the world is broken.’ ‘She has those big blue eyes,’ Basinski agreed. ‘She don’t miss a trick.’

‘My biggest message to queens: we come from the earth,’ ANOHNI told me as I sat in her apartment, the winter light streaming through her white curtains. That afternoon, ANOHNI spoke at length about ecology, violence against trans people, the music industry, art, sometimes second-guessing herself. ‘Am I making sense?’ she kept asking me. More so than most – but I understood how much her creative energy draws from a sorrow that is, at times, inexplicable. I was reminded of a line from James Baldwin’s No Name in the Street (1972): ‘Time […] passes backward and it passes forward and it carries you along, and no one in the whole wide world knows more about time than this: it is carrying you through an element you do not understand to an element you will not remember.’ Certainly, ANOHNI can name the forces arrayed against us (the fossil fuel industry, transphobes), yet their implacable destructive power remains confounding. Why kill this only planet of ours?

‘We are disruptors,’ she said, speaking of the spectrum of queer, trans, nonbinary people whose very existence opposes that destruction. Her eyes became distant, as if she were re-experiencing everyone she had lost, at once. ‘We are born to pose difficult questions. To forge humility in those who occupy extreme positions in the binary, [so they] understand that they all come from a primary humanity and it’s that humanity that the queer body naturally, biologically inhabits.’ It’s a threat so intolerable to those in power that it must be quickly snuffed out. Yet, the fight against erasure continues.

‘Being transgender is a life raft,’ ANOHNI concluded. It can ferry you between those elements of which Baldwin wrote. It can save your life.

Her otherwise bare apartment walls were covered with new works – vertical arrangements she calls ‘lines’ – created from a mix of drawings, paintings and found material from the paper archives she has kept for decades. There was a colourful portrait of Anne Frank ANOHNI painted when she was 14. A Xeroxed letter from Hibiscus. Nightclub flyers. Painted bits of paper. A marked calendar kept by a prisoner, with a line from Psalm 79 printed at the bottom: ‘Let the sighing of the prisoner come before thee.’ At the top of one line, ANOHNI pinned a neon-green poster from a 1991 night at La Escuelita, a now-closed Latinx LGBT bar in Midtown New York. ‘I remember sitting in the front row and just crying while those queens were lip-syncing to Whitney Houston,’ ANOHNI said. Now, the green of that poster flows downward, through drawings and collages ANOHNI created over the years; it swirls and flashes, recedes into the background, leaks into found pieces of paper. ‘It was so touching to me that whoever made this flyer is now circulating through all of this.’

Each small thing that she recycles from her life, from throwaway flyers to old paintings, has a ‘living aspect’, she explained, which delights her as much as it mystifies. ‘It is just so beyond our comprehension,’ she told me. To watch that Escuelita green bleed into other bits of paper, preserved against every effort to stop us from remembering how bright it was, heartened her. Lyrics from ‘The Crying Light’ (2009) played in my head as we stood tracing its journey through the ‘line’, a line that cuts along more than 20 years of ANOHNI’s archive: ‘I need another world / This one’s nearly gone.’

This article appeared in frieze issue 235 with the headline 'Profile: ANOHNI'

Listen to the accompanying playlist, curated by ANOHNI, here

Main image: Amanda Ensigne, Kabuki in ‘The Funeral of Fiona Blue’, Blacklips at the Pyramid, NYC, 1993, video still. Courtesy: Blacklips Archive