Barbara Hammer

Company Gallery and The Leslie-Lohman Museum, New York

Company Gallery and The Leslie-Lohman Museum, New York

In Corky Wick and me, 1979 (2017), a photograph in Barbara Hammer’s solo exhibition at Company Gallery, the artist stands nude in front of a mirror and embraces a woman, perhaps a lover or friend. She unhooks one arm, turns her eyes from her partner, and uses her free hand to snap a photograph into the glass, flash blazing. If any still image could encapsulate Hammer’s work, surveyed concurrently at the Leslie-Lohman Museum, it might be this one. The 78-year-old artist is not one to put distance between herself and her subjects. The experimental queer films for which she is best known are intimate, frequently diaristic reflections on the lesbian and female experience. She often features as an actor, using her own body to express lust and tenderness, or in more recent years, aging and illness. One gets the impression that Hammer is a constant observer, enthralled by acquaintances, paramours, and above all, herself.

This is not to accuse her of narcissism. To the contrary, as these exhibitions demonstrate, Hammer is deeply invested in queer community. Both shows, centered around never-before-seen pieces in varying mediums, situate her filmic practice within a larger iconographic project to represent queer women in a multiplicity of guises, as lovers, warriors, patients or mystics – to give only several examples.

The show at Company features 28 silver gelatin prints shot from 1970 to 1979 and printed in 2017. Some document film and performance production, like Sappho Pre-Production Meeting, Los Angeles, 1978, but the majority are personal photographs taken in California or on trips abroad. Bowsprit, Hornby Island, British Columbia, 1972 depicts a friend sunbathing nude, her back arched against a rock. In Party Time, Montreal, 1979 two women double over in laughter. Folsom Street, San Francisco, 1973 shows figures from the waist down, clad in leather and distressed denim.

Bowsprit is one of many outdoor scenes, and recalls photographs by Anne Brigman and Imogen Cunningham, who staged sumptuous nudes of women in West Coast landscapes. What they did for straight female photographers, Hammer here does for queer ones – naturalizing the explicitly lesbian body and eroticized gaze. Vscape, On The Trail to Machu Picchu captures a suggestive, fertile valley nestled between two mountain peaks; in The Maiden from The Great Goddess (film), Mendocino, California, 1977, a naked female torso is decorated with rings of sand and itself transformed into land art, like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) on flesh.

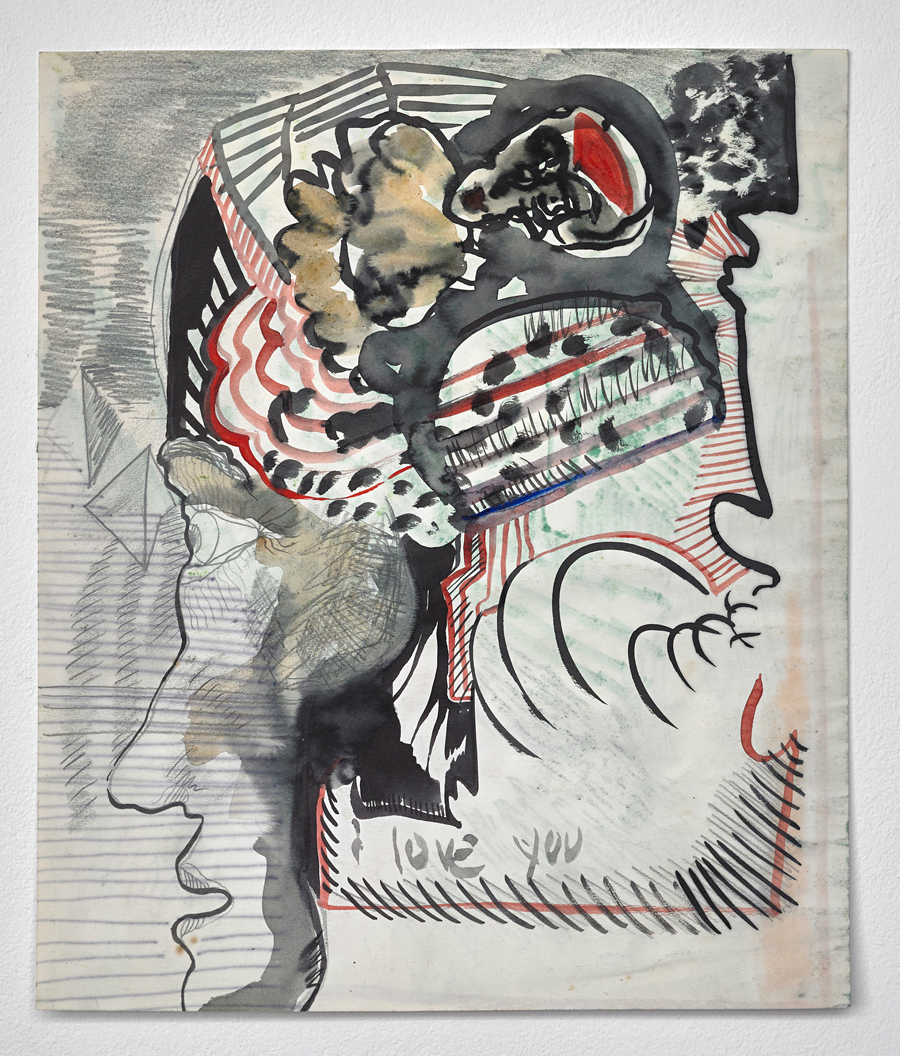

At Leslie-Lohman, documentary video projects, paintings, collages, journals and other ephemera appear alongside 12 better-known films from the 1970s through the 1990s, among them her career-launching sensuous romp Dyketactics (1974). As with the work at Company, these evince Hammer’s quest to find appropriate representation for herself and her community within art and visual culture at large. In two black-and-white photographs, Protegée I and Protegée II (1972/2017), Hammer contorts her body to match the poses of female nudes by Rodin on display in a museum. In the ‘Charlene Atlas’ prints (1998), she superimposes her face onto magazine spreads of famed bodybuilder Charles Atlas. The ‘Merkin’ (1979) drawings and collages abstract lovers’ pubic areas as upside-down triangles. Each is decorated to evoke a different person’s essence: Marilyn, ‘a closely guarded secret’ (according to a description scrawled underneath the picture), is represented by thin grey horizontal lines, while someone named Kathy is imagined as an exuberant combination of red, yellow, green and blue.

8 in 8 (1994), the most viscerally moving piece in either exhibition, comprises a reel of 8 short interviews with breast cancer survivors played on side-by-side monitors. To activate each woman’s story, you press a button buried, like a cancerous node, inside of a synthetic, rubbery breast. Hammer, herself a survivor of the disease, forces her audience to imagine the sensation of discovering disease underneath one’s skin. Female bodies are constantly in flux, as reactive to arousal as to illness, and Hammer leaves no room for passive spectatorship of these many states of being.

Main image: Barbara Hammer, Bowsprit, Hornby Island, British Columbia, 1972, 2017, (detail), silver gelatin print, 39 x 58 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Company Gallery, New York