Dada Africa

Museum Rietberg, Zurich, Switzerland

Museum Rietberg, Zurich, Switzerland

Dada was born in Zurich on 5 February 1916, when Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings opened the Cabaret Voltaire. Among the staples of performances staged there were chants nègres – poems whose rhythms were intended to evoke the cadence of African songs and drumming – and soirées nègres – evening events that included sound poetry, drumming and masked dances, supposedly evocative of African ritual. In these, the dadaists appropriated non-Western art as an antidote to the fundamentally irrational rationality of European culture.

To mark dada’s centenary, Zurich’s Museum Rietberg conceived ‘Dada Africa’, an exhibition exploring the centrality of non-Western art in the movement’s aesthetic and ideological development. (The title is a bit of a misnomer, since the show also includes pieces from Asia, North America, Oceania and Polynesia, as well as some marvellous examples of Swiss folk art.) Driven by Tristan Tzara’s conviction that ‘art needs an operation’, the artists of Zurich’s dada circle seized upon non-Western aesthetics as a scalpel to slice open and, subsequently, reconstruct European culture. The local gallerist and collector Han Coray played a central role in developing dada’s relationship to the ‘other’ – a relationship this exhibition defines as a dialogue, though it is probably better described as one-way traffic from south to north. Coray was the first to display dada works alongside his own collection of African objets d’art, a collection now housed at the Museum Rietberg and that forms the basis for much of the exhibition. The meaning dadaists found in the so-called primitive reflected their own preconceived notions of non-Western cultures: more often than not, they distorted or misunderstood the subjects and objects of their curiosity. The politics of appropriation and primitivism aside, ‘Dada Africa’ makes plain that non-Western art fuelled the movement even more than previously imagined.

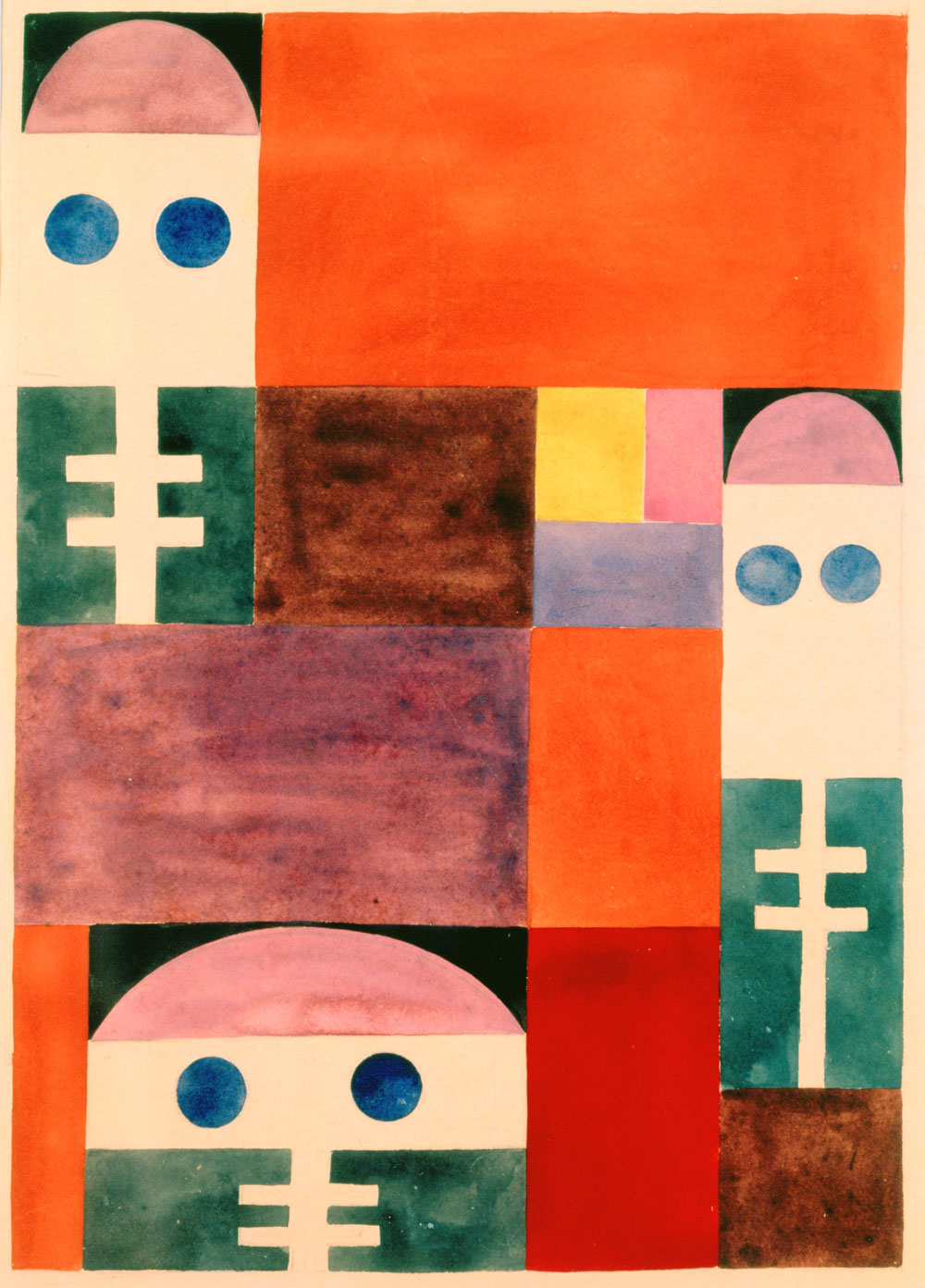

The exhibition is divided into four sections, each examining a specific aspect of dadaist practice: experiments with language, music and ritual, as epitomized by recordings of sound poetry read by Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck and Raoul Hausmann (‘Dada Performance’); modes of display, including images of exhibitions of ethnographic objects from the 1930s (‘Dada Gallery’); the desire to capture the auratic influence of such items, including a striking nkisi figure from the Congo, on the development of Hausmann’s iconic Mechanical Head (c.1920) as well as collages by Hannah Höch (‘Dada Magic’); and appropriation (‘Dada Controversy’). The exhibition’s strength lies in the straightforward juxtaposition of artworks alongside the artefacts that inspired their creation, such as Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s costumes modelled after Hopi katsina dolls and Höch’s ‘From an Ethnographic Museum’ collages (1930), one of which appears alongside the curvaceous torso of the Khmer goddess Uma that it so prominently features. Likewise, the wealth of archival material from dada events illuminates the discourse about non-Western cultures taking place in war-torn Europe at the time. Unfortunately, the dynamic interplay between the dada works and the artefacts that inspired them is constrained by the exhibition’s extreme chronological linearity and rigid architecture – a decidedly un-dada tactic.

The most poignant connection is in the last and only contemporary work, Senam Okudzeto’s Portes-Oranges from 2007. Okudzeto’s installation originated from a trip she made to Ghana in 2003, where she noticed women selling oranges displayed on iron stands at the side of the road. These objects struck her as formally redolent of Marcel Duchamp’s Porte-bouteilles (Bottle Rack, 1914), the first ‘unassisted’ readymade. In swapping spikes for circles designed to hold oranges, the Ghanaian women who had these objects made and put to quotidian use were transforming the dada readymade into what Okudzeto has termed a ‘feminist urban object’, reminiscent of the spare, abstract sculptures that are associated with dada. Okudzeto’s contribution is a reminder of the continued relevance of dada’s belief in the power of art as a vehicle for potentially transformative social commentary.