Data Mine

Travis Jeppesen considers disruption and ambivalence in the work of Simon Denny, in the run-up to the artist’s major project for the Venice Biennale

Travis Jeppesen considers disruption and ambivalence in the work of Simon Denny, in the run-up to the artist’s major project for the Venice Biennale

Simon Denny shifts uncomfortably in his chair. ‘I felt like I was being cast in a role I never set out to play: the Capitalist Artist,’ he tells me. Denny’s Berlin space hardly resembles the classic artist’s studio. Instead, there are A4 printouts of motivational slogans and business mantras plastered across the walls – a messy corporate boardroom, minus the meeting table and chairs.

Just days earlier, Denny had participated in a discussion at the Berlin space of Austrian magazine Spike Art Quarterly. Officially about the current status of the art object, the conversation shifted focus to address broader issues relating to the social context in which art circulates. Without setting out to do so, Denny – an artist who looks to trade fairs and tech-start-up conventions as sources of inspiration – became the voice of both optimism and opposition by refusing to consider as problematic art’s increasing confusion, and infusion, with content by allegedly nefarious market forces. Effectively, Denny was put in the position of having to defend his work as neither ‘merely’ critical nor endorsive, but indicative of a much larger picture of what is at stake in today’s mediascape.

Denny’s work both reflects and investigates the visual as well as rhetorical noise that has come to comprise the urban environments and netscapes of the 21st century. It could be argued that the motivating force behind his ongoing project is disruption, in the sense in which the term is used in The Innovator’s Dilemma – a 1997 book by Clayton Christensen, an associate professor at Harvard Business School – which is a pivotal text for Denny. The prototypical 21st-century example of Christensen’s thesis would be the iPhone, a product that effectively disrupted an entire industry when it came out by immediately making all other mobile phones look obsolete. While we might recoil from the term ‘innovation’, with its connotations of branding and corporate speak, when applied to an art context, it’s not as misplaced as it might seem, since it harks back to one of the canonical slogans of modernism: Ezra Pound’s ‘make it new’. That Denny relies more upon entrepreneurial than critical theory is only one of the ways in which his work effectively disrupts critical norms predominant in contemporary art.

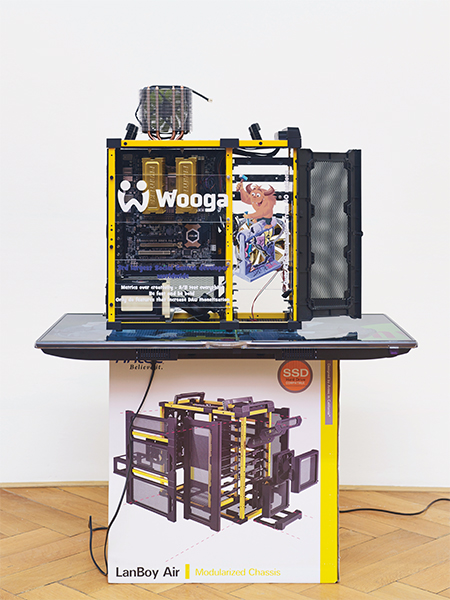

This concern with disruption surfaced most directly in Denny’s 2014 exhibition at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, entitled ‘Disruptive Berlin’, in which he made ‘sculptural portraits’ of ten leading start-up companies based in his adopted home town that used elements of their own products and advertising. For example, for his portrait of Wooga, a mobile-first game developer, Denny strapped together packaging, a computer case, a Samsung monitor and a display case with computer hardware featuring the Wooga logo (Berlin Startup Case Mod: Wooga, 2014). A sort of deceptive homage, these assemblages can be seen as a form of subversive bricolage, in that the final product looks unfathomably other than what the company’s creators ever would have imagined.

This kind of work promises confusion. In a similar vein, Denny presented ‘All You Need is Data: The DLD 2012 Conference REDUX’ in 2013 (first at Kunstverein Munich and then, announced as a ‘rerun’, at Petzel Gallery, New York) – a recapitulation of the 2012 Digital-Life-Design Conference (DLD), an annual, invitation-only event bringing together A-list representatives from the media, arts and technology worlds. The exhibition consisted of 89 digitally printed canvases that summarized what took place at the conference via pull quotes, bullet-pointed texts, graphics and photographic documentation. Denny’s editing allowed such seemingly uplifting phrases as ‘sharing economy’ and ‘start-up nation’ to appear alongside quotes of embarrassing pronouncements, like: ‘If you’re not started by 22, funded by 23 and able to retire by 24 to 25, then you’ve failed.’ When Denny attended DLD in January this year, in order to present his take on the 2012 conference in a programmed talk to the attendees, he was met by bafflement. His audience, on seeing their self-marketing repackaged and rebranded by an outside(r) agency, and on being confronted by images of their companies that they had no control over, found themselves at a loss as to what to make of it.

[Missing Image]

‘All You Need is Data’ and ‘Disruptive Berlin’ are among the six recent projects that feature in Denny’s largest us institutional exhibition to date, ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’, which opened at MoMA PS1 in New York in April. Another project, ‘The Personal Effects of Kim Dotcom’, originally exhibited in 2013 at MUMOK in Vienna, is similarly inventorial, depicting in graphic form across 110 stretched canvases everything taken from the German-Finnish internet entrepreneur Dotcom in the 2012 police raid of his New Zealand mansion, as well as sculptural copies of some of the seized objects, including jet skis and motorcycles. In Berlin, Denny had been using Dotcom’s file-sharing site, Megaupload, to stream English-language television shows and transfer large files of his own work. When Megaupload was shut down, Denny became obsessed with the site’s incriminated owner, and began reading whatever he could find about Dotcom. When he came across an inventory of everything that had been seized in the raid, he knew he had found what he needed.

The backstory of Denny’s exhibition on the Dotcom raid expresses an important facet of the artist’s practice: the primacy of research. Only rarely does Denny have any idea what the final exhibition product will look like when he starts exploring a certain area of interest. The word interest is key here; Denny’s integrity rests on the fact that he follows his phenomenal obsessions free of bias, whether they be products of Silicon Valley or intergovernmental spy networks. (New Zealand’s Dotcom bust was a collaborative endeavour with the us government.) In doing so, he frustrates efforts to judge the political correctness behind his intentions.

Talking about his upcoming exhibition at the Venice Biennale, Denny is reluctant to reveal too many details, fearing he may jeopardize the immediate impact he anticipates the work will have on viewers. The show takes its title, ‘Secret Power’, from a 1996 book by Nicky Hager, a controversial investigative journalist from Denny’s native New Zealand, who is currently working to disseminate many of the leaks made by Edward Snowden that implicate New Zealand in having collaborated with the US government in its spying activities. Denny offers only the sparest information: the project will unfurl across two venues, the first being the arrivals area of Venice Marco Polo Airport – cleverly ensuring that this will be the first art nearly every visitor to this year’s Biennale will see. This installation is being created in collaboration with a multi-international advertising firm and will, Denny promises, be something that tourists as well as Biennale visitors will be able to engage with. ‘Secret Power’s second, main venue will be Venice’s Marciana Library. One of the city’s hallmark works of Renaissance architecture, the Marciana will make both a grand and thematically enriching backdrop to Denny’s work. The library is home to a collection of original Renaissance maps that have been key to the conceptual development of the exhibition, which will contrast the ways the world was mapped then (not just physically, but also in terms of networking and infrastructure) and is today.

Although ‘Secret Power’ is due to open just two months after my visit, there are few clues in Denny’s studio as to the specific nature of what it will contain, save for a group of skeletal foundations of wheeled carts that the artist hints will serve as display cases. Denny likes to stress that he is a maker of exhibitions, rather than individual artworks. The experiential nature of these exhibition-events is intended to replicate the immersive nature of a spectacle – in this case, the trade-fair, with all its nervous and excited energies. For this reason, it makes sense that Denny doesn’t want to spoil the surprise in Venice – or jinx his ongoing research efforts. Already, owing to his work with Hager (Denny took him on as an adviser for ‘Secret Power’), influential figures from the New Zealand elite have allegedly retracted their endorsement of Denny’s project at this year’s Biennale. So much for him being ‘the Capitalist Artist’.

In fact, Denny is making work with political implications that is politically uncategorizable. Nothing in his practice actively curtails a potential (post-/neo-) Marxist reading, nor an accelerationist reading, for that matter. In a subversively subtle way, Denny’s work might posit an alternative to both positions. His is a rigorous portraiture of the present’s rhetoric, parsing bits of noise that we might otherwise overlook, and forcing us to re-consider: a process that is endless, difficult and inevitably results in ambiguity – as much for the artist himself as for the work he produces.