The History of Washington D.C.’s National Museum of Women in the Arts

Featuring Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, ‘Womanhouse’ marks the 30th anniversary of the museum dedicated to women artists

Featuring Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, ‘Womanhouse’ marks the 30th anniversary of the museum dedicated to women artists

A sticker of Camille Claudel is on my collar and a woman is pounding at a wall; another, with dirty feet and a red party dress, is crawling the walls and slithering over shelves. In the next gallery, a house sprouts from a marble woman. Meanwhile, men in heavy-framed glasses and 1970s suits shake their heads, as if passing judgment on all that surrounds me. I’m at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., in ‘Women House’. The exhibition takes Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s seminal experiment in immersive art education ‘Womanhouse’ as its starting point. Back in 1972, Chicago and Schapiro started a Feminist Art Program at CalArts in a dilapidated house that became both classroom and exhibition space. A documentary about the course shows the work with performances limning out the monotonous expectations of a woman’s life, and the students in seminars-as-encounter-groups and feminist consciousness-raising, while the men in their suits respond with skepticism.

‘Women House’ explores the same realms of the domestic as the original project and explodes the notion that women’s art is somehow always about domesticity. The home is, indeed, the theme here, but there is nothing obviously maternal in the work. All 36 artists tackle the weight of such expectations; together, they make me think of Richard Serra’s work, as if the exhibition’s subject itself is as monumental a material as his Corten steel – as if the vehemence directed at the home, the pounding and the implosions have as much power as his sculptures tried to muscle into being.

The exhibition is part of NMWA’s 30th anniversary. When the museum opened in 1987, I was a suburban teenager with pink hair, a black wardrobe and a list of heroes who weren’t exactly standard rebellious teen fair: Linda Nochlin, Adrienne Rich and John Ruskin. I grew up outside DC, believed in Marxist feminist art history and had an aunt who gave me the NMWA’s inaugural poster. Hung in my bedroom amid posters of DC punk bands and Siouxsie Sioux, the image always broke my heart a little. It featured type and a reproduction of Lilla Cabot Perry’s Lady with a Bowl of Violets (1910). A Whistler-like composition, the woman poses in three-quarter view and a diaphanous dress. She’s luminescent with fantastic cheekbones but, painted as it was in 1910, this ‘lady’ weighed on me. ‘Why paint like that in 1910?’ I wondered. It was as if Cabot Perry had missed the teleology, the chronology, of modernism. Despite all I knew about women’s art and history, about why there were no great women artists, I was disappointed in the poster and the institution’s staid goals and its grand empty entrance with its pink marbleized columns. The pink felt like an affront – and I wasn’t the only one let down.

The New York Times sent three different women to cover the opening: Roberta Smith (‘leaves much to be desired’), Grace Glueck (‘born with a silver spoon in its mouth and bred to be noncontroversial’). Ann Beattie wrote of the dangers of ‘segregation’ and worried the museum would ‘make such a strong statement’ that it would cross some line.

It’s hard to believe now that a museum dedicated to women’s art might be seen as a step too far. The 1987 edition of H.W. Janson’s History of Art (first published in 1962) had included women for the first time, and Glueck quoted other curators whose remarks seem shocking. Lowery Sims from the Metropolitan Museum of Art: ‘One wants to believe there is already enough integration of women and minorities into the art establishment.’ John Wilmerding of the National Gallery of Art: ‘We like to consider art in terms of its merits, rather than its makers.’ Even Schapiro, who was responsible for ‘Womanhouse’ and whose Dollhouse (1972) is a centerpiece of the current show, was ‘ambivalent […] the code here is Junior League,’ she said, calling out the NMWA’s conservative plans (according to Glueck politics and abortion were off limits). Chicago, however, said she’d support the museum and donated a piece to its collection. Smith pronounced that it was important to give the institution, ‘a grace period of a few years’.

Flash forward not three years but three decades and the grand entry is still pink and the museum’s founder, Wilhelmina Holladay, towers over the entrance in a portrait traditional enough to make the Cabot Perry look experimental. But, a woman pounds the walls in Monica Bonvicini’s Hammering Out (an old argument) (1998) and another presses her body into the limitations of walls and spaces in Lucy Gunning’s video Climbing Around My Room (1993) and the institution now has collection of 4,500 works (ten times what it opened with).

Susan Fisher Sterling started at the NMWA in 1988 as a curator in modern and contemporary. Now she is the director. Her office is scruffy, scattered with papers, as if trying to contain all her ideas. A Grayson Perry tea towel is draped over the windowsill. ‘Hold your beliefs lightly,’ it reads. A Jenny Holzer paperweight declares: ‘Use what is dominant in a culture to change it quickly.’

In grad school Fisher Sterling had asked her professor: ‘Could we look at work by Joan Mitchell or Louise Bourgeois or Lee Krasner?’ and he replied: ‘Oh yes, we can throw them in. They can be comparative source material.’ She tells me this story, repeats ‘source material’ and shakes her head. It’s the kind of comment which, like those from Wilderming and Sims, can make that time seem like a distant realm. Now Washington has free federally supported museums such as the National Museum of American Indian and National Museum of African American History and Culture. But, nothing for women. When Wilhelmina Holladay founded the museum, she didn’t call it the Holladay Collection but the NMWA, as if the ‘national’ could channel a larger goal. But the institution is still private, still requires an entrance fee (hence my Claudel sticker) and is still the only museum dedicated to women in the world, even if that world has changed. Fisher Sterling says: ‘I used to think in ten years the problem would be solved and women artists would receive this equality we were working for and we’d become part of the Smithsonian.’ She laughs. ‘Fast forward and it’s a 100-year project.’

She talks too about how parity remains a chimera. ‘You still get two to seven percent women artists exhibited even as you head into modern and contemporary sections of museums and when you look at Forbes, with the top 500 CEOs, they’re still less than five percent women. Museums are not alone. This is where women are in culture. It’s a systemic issue.’ She says that in the art market, of the top 100 artists only two to three are women. ‘You can’t get away from the art market as you think of how women are valued.’

Downstairs the permanent collection is hung thematically. One gallery is organized around the natural world. Anne Truitt’s sculpture Summer Dryad (1971) – a minimalist tower in two bold grassy greens named for a forest nymph – stands next to engravings of insects and butterflies by an 18th-century naturalist, Maria Sibylla Merian. The painter Lee Krasner is adjacent to a radiant Alma Thomas canvas, Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses (1969). Both are a few feet from Clara Peeter’s creepy Still Life of Fish and Cat (ca 1620). It hangs just below Sharon Core’s photograph Early American Tea Cakes and Sherry (2007) but with more food, which adds to the strangeness. Core restages and reinterprets the still life with photography, and Peeter’s cat comes off as more menacing. Together the works add up to something powerful, a bit like how the work in ‘Women House’ did as it tackled domesticity. Peeters and Core both seem to tug at the seams of the still life tradition to question it. ‘Chronology,’ Fisher Sterling says, ‘is the enemy of women and people of colour.’

Chronology eliminates them and begins to look like teleology, in the way I had thought of Cabot Perry. Chronologies make it easy to overlook anyone who doesn’t hew to their lines or seem to be moving on to this or that next great thing. Thematic hangings give a weight and anchor to all the work. You can see how women have grappled with a subject like nature to which they were often relegated.

‘It doesn’t look like portrait, portrait, portrait, still life. This is all women traditionally were allowed to do,’ Sterling says. It wasn’t that way at the museum’s start. The inaugural exhibition, ‘American Women Artists 1830-1930’ reiterated the assumption that women were stuck in the crevices and sidelines – instead of exploring the way those crevices could yield to a deep seam of study over centuries.

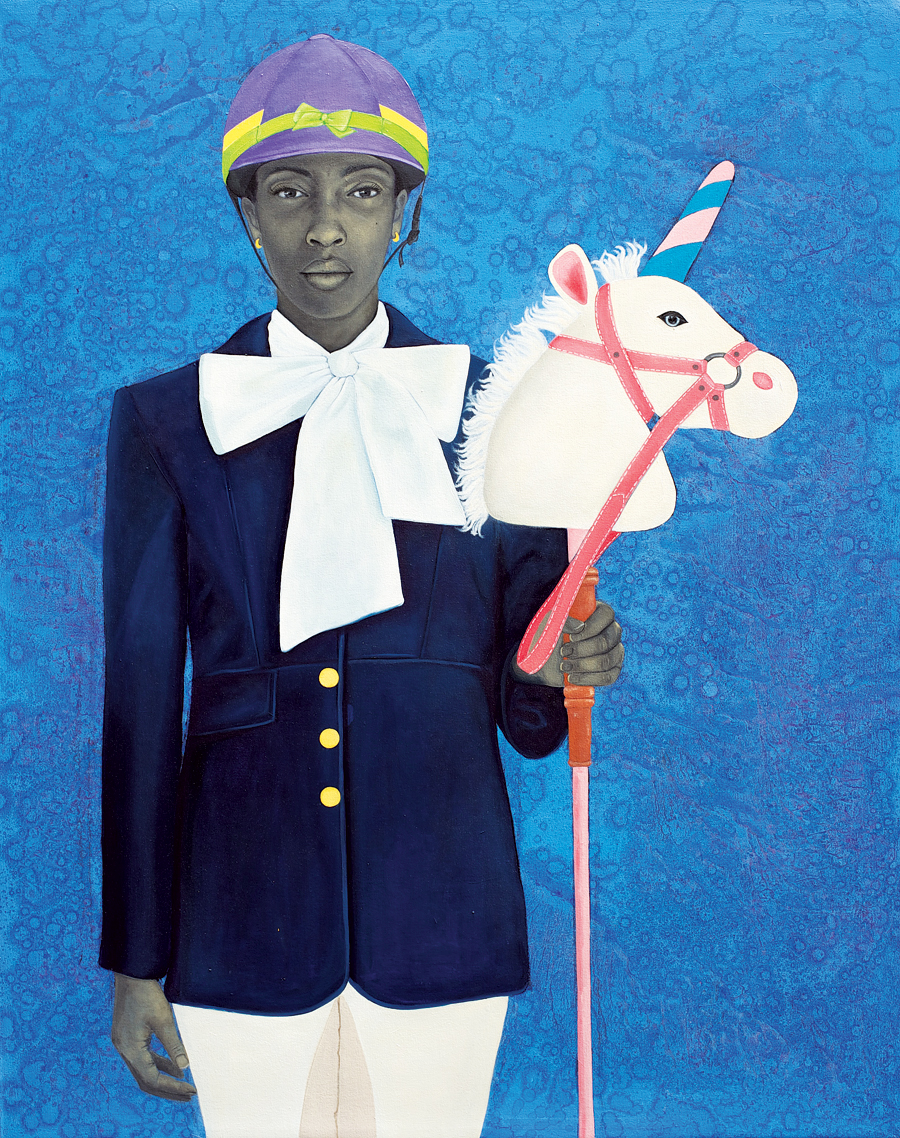

In the permanent collect Cabot Perry now hangs near May Stevens’s Soho Women Artists (1978). Laid out like a history painting, the women form a frieze across the canvas with two old men, Soho locals, blurred on the side. In the centre, Sarah Charlesworth holds her bicycle next to Louise Bourgeois wearing a sculpture. There’s Miriam Schapiro, Joyce Kozloff, Harmony Hammond, Lucy Lippard and May Stevens. Across the room hang two Amy Sheralds and two plaid abstractions by Andrea Higgins. They riff on the modernist grid but are both portraits; one is simply called Hillary (2002). After staring at it for a while, I realize that the weave is taken from Hillary Clinton’s pantsuit; likewise, Jackie (Dallas) (2002) is a reference a pink Chanel. In those poles between Cabot Perry and the plaids, the world has changed, though clearly not enough.

Published in Frieze Masters, issue 7, 2018, with the title ‘Pounding the Walls’.

Main image: May Stevens, Soho Women Artists, 1978. Courtesy: the artist, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, and Ryan Lee Gallery