Inhuman

Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany

Fridericianum, Kassel, Germany

‘Inhuman’ is the final part of a trilogy of exhibitions featuring art of the post-internet generation curated by Fridericianum’s director Susanne Pfeffer. Its title comes from Jean-François Lyotard’s 1992 book The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, in which he asks: ‘Can thought go on without a body?’ Like the previous two exhibitions, ‘Speculations on Anonymous Materials’ (2013–14) and ‘nature after nature’ (2014), ‘Inhuman’ asks us to consider how our world will be transformed by new technologies, changing socioeconomic conditions and advances in neuroscience. But upon entering the museum, my first thought was, ‘This is the future?’

In the first room, sets of metal bars, like those used to guard windows, were mounted on or leaned against the walls. Hanging from these, were pink and bluish scraps of silicone, resembling torn flesh or viscera, sprouting human hair. These Security Window Grills (2014), by Steward Uoo, are meant to be repulsive – and they are. Turning away in disgust, my eyes came to rest on Jana Euler’s under this perspective, 1 (2015), which is ostensibly a portrait of a woman lying on her stomach, but is so distorted that it looks like two large feet that merge into a penis-shaped body with a tiny set of hands and a small head.

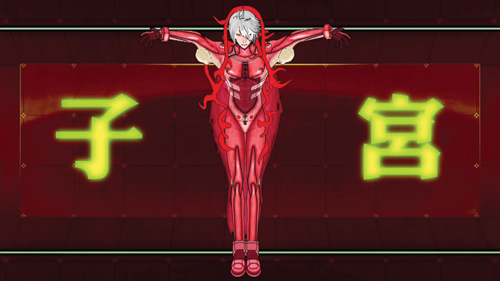

In the next room, Lu Yang’s 3D animated film, UterusMan (2013), tells a dramatic tale of a kind of anime female superman who takes on the form of a womb and fights enemies by firing egg cells from his/her uterus. Lu’s vision of pregnancy, birth and motherhood is a radical departure from traditional notions of gender and sexuality. Cécile B. Evans’s video Hyperlinks or It Didn’t Happen (2014) was a similarly fantastic tale, in which dreamlike images narrate the story of an actor who dies while shooting a blockbuster film series and must be digitally re-animated for the final part of the franchise. Evans’s beautiful imagery makes it easy to forget that the video is ultimately about the fate of our online presence after we die. Though Evans’s film is gorgeously melancholic, it was an exception in an exhibition of works that were generally sterile, cold and distanced. This sense of isolation was evident in Melanie Gilligan’s ten-part video installation The Common Sense (2014–15). In Gilligan’s sci-fi world, a ‘patch’ is placed under a user’s tongue, enabling his or her feelings and sensations to be shared directly with others. The invention raises great expectations for the future of companionship and security, but it soon becomes apparent that the patch is only being introduced to optimize capitalist strategies. The dream ends like so many that involve new technologies: dreams of transparency and closeness give way to control and constant surveillance.

Scraps of flesh, a uterus mutated into a male figure, re-animated film heroes – rarely have the objects in an exhibition seemed so collectively monstrous. Is this really how this generation of artists envisions the future? ‘From the perspective of the present, the future of humanity might be monstrous [...] but this is not necessarily a bad thing,’ writes artist Julieta Aranda in a booklet accompanying the show. The exhibition itself, however, offered little comfort. Instead, it suggested that new technologies are producing more quasi-objects and quasi-beings like UterusMan, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish nature from technology, subject from object. The show also reflected a paradox: the more life is animated and permeated by computer-generated technology, the more confused and complicated the questions of the material and the immaterial, of death and immortality become – even though, ironically, so much technology was developed with the hope of resolving precisely these questions.