Would You Pay to Live in Facebook’s Metaverse?

As Silicon Valley’s latest buzzword picks up traction, Kyle Chayka investigates if this new ‘utopian’ space is just yet another poorly regulated economy

As Silicon Valley’s latest buzzword picks up traction, Kyle Chayka investigates if this new ‘utopian’ space is just yet another poorly regulated economy

When I was in middle school in the early 2000s, I became obsessed with Ragnarok: Online (2002): a massive multiplayer online role-playing game made by a South Korean company called Gravity. I lived and breathed it, spending all my time outside of school cultivating a character in the fantasy-game world and a community around it, through online forums. It was immersive and satisfying; unlike the social world that I inhabited in real life, it made sense, offering linear rewards for time invested.

Eventually, I had the realization that this digital world wasn’t as organic or democratic as it first seemed. It was my first time participating independently in an economy planned from above, with fictional resource scarcity and an in-game currency created by the developer. Each year around Christmas, the game would host a holiday week that featured special items like Santa hats, which players would briefly obsess over, driving up the cost, before they disappeared again. My experience of Ragnarok was one that others had with World of Warcraft (2004) or RuneScape (2001) or Neopets (1999): the virtual world is utterly compelling until its falsity becomes obvious, the numbers game too transparent.

I’m reminded of Ragnarok every time I hear the term ‘metaverse’ – the latest in a long line of Silicon Valley buzzwords, such as ‘sharing economy’ or ‘the singularity’, that stretch meaning to its limits. To tech entrepreneurs, the metaverse future sees all digital platforms converge. It’s a realm that our avatars could walk around – like a massive multiplayer online role-playing game – but which also encompasses all of our digital activities, from posting photos of our friends to streaming television shows. In fact, the word originated in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science-fiction novel Snow Crash, where the metaverse is controlled by one corporation, the Global Multimedia Protocol Group. Stephenson’s version is more hardboiled than utopian; it’s not a place anyone would aspire to live.

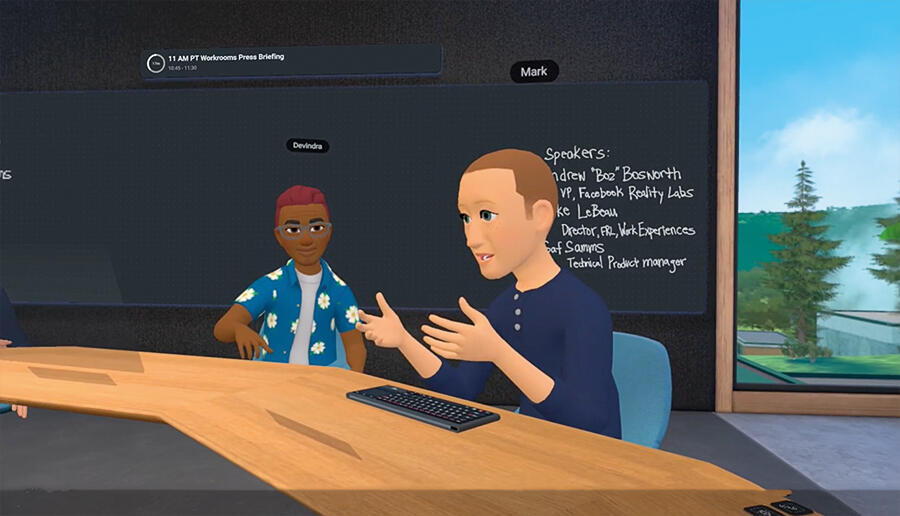

Technology companies are now racing to stake a claim in the metaverse. In an interview with The Verge in July, Mark Zuckerberg argued that Facebook will transition over the next five years from being a social-media company to a ‘metaverse company’. Blockchain-technology projects such as Decentraland and The Sandbox are creating and selling parcels of virtual real estate. Epic Games, creator of the massive multiplayer online game Fortnite (2017), announced a US$1 billion funding round to construct the metaverse.

Epic recently filed a lawsuit against Apple over its own gated digital space, the App Store, which is the only way for developers to access hundreds of millions of iPhone users. Apple charges up to 30 percent of developers’ revenue as a tax for using the platform. When Epic attempted to bypass this system, Apple banned its games from the App Store. The legal challenge has been successful to a certain degree – Apple has lowered the percentage of its cut – but the company still dictates what is allowed in its store.

Fortnite is already a kind of metaverse. While the game is primarily about shooting other players in a frenzied melee on an island until only one survives, it has evolved into more of a digital sandbox. Competition is often less the point than just hanging out, virtual socializing. Games like Roblox (2004) and Minecraft (2009) exist in the same genre. But there’s a clash between the content of these game-worlds and the platforms they exist on. The metaverse-style spaces are supposed to offer complete independence, an unprecedented openness of creative opportunities, yet they aren’t truly independent at all.

The metaverse is less a new space than a new economy, one in which a single business dictates every aspect of an experience: there is no possibility that isn’t predetermined. That isn’t to say creativity is impossible – Second Life (2003) created a precedent for shared, user-generated virtual spaces where self-expression was just as important as any kind of material accumulation. The artist Cao Fei used Second Life to create the virtual exhibition space RMB City (2009–11), which hosted events that spun out into physical shows and video works.

But Second Life is the rare, metaverse-style space that isn’t overly commoditized or forced to grow at unsustainable rates to accommodate a large swathe of the world’s population. It’s hard to imagine a company like Facebook allowing for such projects, particularly when it already encounters censorship in countries including China. An open metaverse might be forced to rely on a benevolent overlord that tolerates its users’ freedom. The other option is blockchain decentralization, which may be free of censorship but currently consumes more electricity than some entire nations.

The utopian metaverse vision: anything can become its own universe. Each cultural element grows into a space in which users, fans and viewers can participate. But when corporations latch onto such vocabulary, the future seems less hopeful. There’s a sadness that comes with reaching the end of a rigidly corporate online space, like wandering to the edges of an amusement park. After a year or two in Ragnarok, I soured on the manipulative mechanics of novelty that no digital socializing could enliven. It amounted to a kind of digital capitalist consumerism, with the gain of new onscreen items and imagery the endpoint. Since that is how companies profit, the metaverse seems destined for the same fate.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 222 with the headline ‘Reality Bites´.

Main image: Ragnarok Crusade, 2021. Courtesy: © Gravity Interactive