Martha Rosler Still Brings the War Home

A retrospective at the Jewish Museum, New York, explores how the artist has continued to insist on the violent costs of our domestic comforts

A retrospective at the Jewish Museum, New York, explores how the artist has continued to insist on the violent costs of our domestic comforts

A study published recently by Brown University’s Watson Institute revealed that wars waged by the United States since 9/11 – whether in Afghanistan, Iraq or Pakistan – have resulted in the deaths of half a million individuals. It seems only fitting, then, to look again at Martha Rosler’s 'House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home' (c. 1967-72; 2004-2008), a photomontage series completed first during the Vietnam War, and reprised following the US-led invasion of Iraq. In Red Stripe Kitchen (1967-72) we find an advertisement for a modern kitchen disconcertingly invaded by a pair of American soldiers on a reconnaissance mission; Amputee (Election II) (2004) reveals an American soldier outfitted with a prosthetic leg walking across a living room adorned with a photograph of a jocular Jeb and George W. Bush. Vietnam was dubbed the ‘living room’ war for its newly televised presence – a fact that Rosler’s montages literalize, bringing the war home twice over. If today America’s military manoeuvres remain largely out of sight, Rosler has continued to insist on the violent costs of our domestic comforts – an insistence this exhibition details with the full gamut of her multimedia practice over five decades.

‘Irrespective’, the survey’s playful portmanteau title, merges the words ‘retrospective’ and ‘irreverent’ – the latter an unrelenting dimension of Rosler’s politically engaged practice. Opening with dual sets of montages from the two House Beautiful series, the exhibition radiates outwards like spokes from an axis, proceeding both chronologically (in fittingly counter-clockwise fashion) and thematically, in a remarkable range of formats: from video (of which she proved an early pioneer) and photomontage, to installation and photo-text panels. Pervading this work is an unswerving concern for social justice, at both the local and global levels. Indeed, perhaps the most impressive aspect of Rosler’s practice is how she uses specific urban spaces – and the lives of their subjects – as concentrations and refractions of more far-reaching ideological networks.

Rosler first explored the politics of New York city’s urban life in The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974-1975), a series of photographs of New York’s Bowery juxtaposed with typed vernacular euphemisms for drunkenness – a play upon the neighbourhood’s (former) ill repute. By photographing only shopfronts and discarded liquor bottles, Rosler deliberately avoided the sensationalism of poverty’s subjects. If the piece recalls the topographic, documentary efforts of Eugène Atget or Walker Evans, its self-avowed ‘inadequacy’ simultaneously interrogates the end game of documentary photography itself. So, too, do the photomontages of Rosler’s 'Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain' series (c. 1966-72) articulate new representations using the language of advertising, while ironizing those very regimes of representation, particularly their depictions of gender. An image like Cold Meat II, or Kitchen II reveals a refrigerator stocked with comestibles as well as a giant set of breasts – a mordant conjunction of commodities which Rosler pursues in a number of different projects, from her video The Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) to her ongoing photographs of airports in'In the Place of the Public: Airport Series' (1983-present).

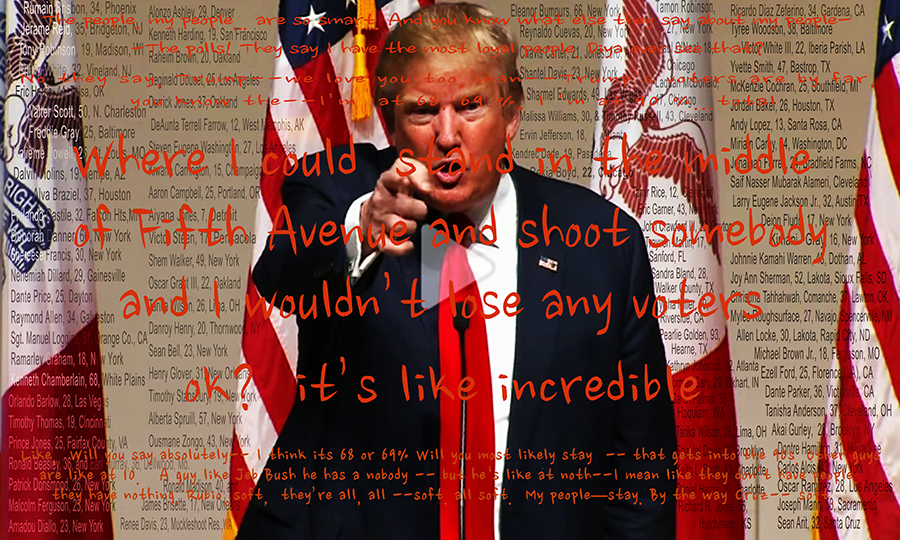

The show’s concluding room contains the transparent curtain printed with text, Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century) (2006), bearing excerpts of Arendt’s writings in both German and English. Yet Rosler continues to make polemical and provocative interventions. The digital montage Point n' Shoot (2016) reveals a looming photograph of Donald Trump, overlaid with his infamous remark about being able to gun someone down on Fifth Avenue without losing voters. Behind him reads a monumental list of individuals of colour killed in recent years by police officers acquitted of their murder.

As Amazon.com moves to set up shop in Long Island City – with billions of tax cuts in hand and an expanding raft of employees – the stakes of gentrification have never seemed higher. Rosler’s Greenpoint Project (2015) – which documents both storefronts and personal testimony of residents in the adjoining Brooklyn neighbourhood – registers the incredible diversity of its immigrant communities. Like her work on the Bowery, the project stands as both a benchmark and a beacon in the intersection of art and activism – though it is the humour and pathos of its aesthetics which separates it from mere didacticism. Almost impossibly, Rosler’s work manages to be at once accessible and incisive, impish and profound.

Martha Rosler, 'Irrespective' runs at the Jewish Museum, New York, until 3 March 2019.

Main image: Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon) (detail), from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967-72, photomontage. Courtesy: the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York