Nil Yalter’s Epic Poetry

The artist takes us through her multi-faceted practice, now on view in her retrospective at Museum Ludwig, Cologne

The artist takes us through her multi-faceted practice, now on view in her retrospective at Museum Ludwig, Cologne

Over four decades, Nil Yalter’s artistic journey has led her to India and Iran on foot, to leftist uprisings in the Middle East, to field research with nomadic women in eastern Anatolia and to undocumented migrants in Paris. Her itinerant, intersectional work – spanning sculpture, film, activism, interactive media and painting – is now on view in ‘Exile Is a Hard Job’, a major retrospective at Cologne’s Museum Ludwig

Övül Ö. Durmusoglu: Gertrude Stein once quipped: ‘What good are roots if you can’t take them with you?’ You were born in Cairo, raised in Istanbul, where you started your artistic work at an early age, and have lived for decades in Paris, where we are today.

Nil Yalter: What Stein says is very true. My roots didn’t matter much to me when I left Istanbul for Paris in 1965. I was driven by a thirst for new art being made in Europe and the US. But, after a while, I realized I wouldn’t be able to make anything without confronting my own heritage.

ÖÖD Did you return to Turkey during that time?

NY Yes, I was constantly travelling back and forth. My work Topak Ev (Nomad’s Tent, 1973) was a turning point in my practice. I was researching the Central Asian collection at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, with the help of anthropologist and ethnomusicologist Bernard Dupaigne. The work also resulted from field research I did in Niğde, in central Anatolia, with still-existing nomadic communities. In these communities, each tent is the domain of a single woman, who takes care of her family within it. I built the structure in aluminium and covered it with felt and sheepskin. I painted abstract forms on the skins and stitched excerpts from Yaşar Kemal’s novel The Legend of the Thousand Bulls (1971) – an ode to the nomadic people of Anatolia – alongside Velimir Khlebnikov’s futurist poetry about the itinerant peoples of the Kalmyk Steppe.

ÖÖD What did you encounter in Niğde?

NY For one, every woman in the communities I visited had a husband, brother or uncle who went to Istanbul to find work and wound up in a shanty town. Many of them ultimately left for Germany or France. This led me to collaborate, in the following years, with contemporary nomads: migrant workers.

ÖÖD These were years of sharp political turns: the 30 days of students’ and workers’ protests in France in 1968; while, in Turkey, two military interventions, in 1960 and 1971, saw democracy suspended. What was your artistic environment like during this time?

NY The period around 1968 was very important in the West but also in the whole world. Afterwards, female artists especially experienced a big leap in consciousness, and a line of activism opened up.

Prior to 1981, I did a lot of research for Topak Ev, Deniz Gezmiş(1972) and Rahime, Kurdish Woman from Turkey (1979)in Turkey, but realized the works in Paris. It took me seven years, from 1965 to 1972, to understand and digest the philosophical, literary and artistic developments in the West. The working process followed.

I continued to travel to Turkey until 1981. The artistic community there had not experienced this critical leap. Turkey’s cultural scene was in difficult political straits. Artists, male and female, lacked visibility. But it is important to say here that female artists in Turkey, in my experience, didn’t face enmity or discrimination during this time. That started recently, with the polarizing effect of the current government in daily life.

ÖÖD And Turkey had a small but dynamic artistic scene before that.

NY The end of the 1950s and early ’60s had been more interesting. Art wasn’t contemporary and it wasn’t a major cultural field compared to literature, theatre and cinema. But we tried to do things by looking at a few reference books. In the 1970s came great political pressure, which culminated with the coup in 1980. The main breakthrough in Turkey for contemporary art came in the 1980s. Since I wasn’t able to travel to Turkey between 1981 and 1993 [due to the political climate], I couldn’t experience this important shift in person.

ÖÖD Before this period, you journeyed through Iran and India on foot as a pantomime performer with your then-partner.

NY That was not only a journey to Iran and India; it was a cosmic experience. We decided to set out on foot – an impromptu decision that shocked everyone around me. They doubted I could reach Ankara on foot, let alone Iran. They thought I’d reach the eastern Anatolian city of Erzurum, at the farthest. But they couldn’t stop me. I returned one and a half years later. Did I go to India, the cosmos or into outer space? I still don’t know.

We didn’t have any money, so my comrade and I needed to support each other and work together. Once, in south India, we gave a pantomime performance and were given a beautiful hotel room. He refused to sleep on the bed, not wanting to get used to such comforts. I returned to Turkey eventually, but he continued to travel in this spirit for many years.

ÖÖD Did you know you would leave again after returning?

NY Afterward, I couldn’t stay home. Nobody could have made me start a family and become a housewife. It all ended there. It had been more than physical travel. My comrade returned after ten years and secluded himself. He wrote a few books, one also on our experiences, but he didn’t do much because he was on the more radical and mystical side. The journey triggered me to produce more.

ÖÖD You’ve said that when you started to collaborate with migrant workers in Paris, your work was labelled as politics, not art. Today it’s clear that your art and politics supported and nourished each other.

NY There is a divide and, yet, there is no divide. This stems from the highly politicized atmosphere in Turkey. All my artist friends there, mostly painters, people I grew up with until I left, were politically active and many were imprisoned. But the execution of student leader Deniz Gezmiş and his circle, in 1972, led me to develop a political stance in my art.

ÖÖD You were in Istanbul in 1971, when the Turkish state, under martial law, prosecuted the dissident People’s Liberation Army of Turkey (THKO). This led to death penalty counts against 18 people, including Gezmiş, Hüseyin Inan and Yusuf Aslan, which caused a huge outcry in Turkey. The ruling was ultimately revoked due to major public pressure, but not until Gezmiş, Inan and Aslan were hanged. This situation changed the course of political history in the country.

NY For years, we had lived with capital punishment very normally in Turkey. When Prime Minister Adnan Menderes was executed in 1961, we experienced that violence as if it were normal. But the killing of Gezmiş and his circle changed everything. Turkey ultimately abolished capital punishment. France woke up, too. Now, there are calls to bring back capital punishment – a catastrophe. Some of the Gilets Jaunes voice this desire. It is unacceptable.

My work about Deniz Gezmiş marked a political awakening in my art. I also started to pursue political activities outside my artistic work. I could never vote in Turkey – and there were military coups d’état, one after the other.

ÖÖD In those days, after shutting yourself in a friend’s apartment, you collected all the news clippings about Gezmiş, Inan and Aslan and produced a series of artworks as an act of presence in the face of their scheduled execution. Then you took the project with you to Paris and showed it only to your friends. The work in its entirety is currently on display for the first time in ‘Exile Is a Hard Job’ at Museum Ludwig.

NY The enlightenment I experienced while making this work – comprised of paintings, newspaper collages and photos my friend had taken of my room – was a very bitter one. Ruminating on Gezmiş’s time at court, capital punishment and execution was a ritual of harsh awareness and it informed some of the radical positions that I have taken in my life subsequently.

ÖÖD Let’s turn to your relationship with feminist politics. Is it possible to view the strengthening of feminist movements around the world today as a counterweight to the brutality that is also increasing?

NY Wherever violence increases, the situation of women becomes worse, too. Feminism led to crucial shifts in developing resistance. However, when we speak of feminist movements, we need to question how many billion women live on this planet – and the small percentage that have access to these opportunities while many continue to live in medieval conditions. To what degree is it possible for a woman living in a small Anatolian village to share our opinions?

ÖÖD Your works use documents and documentation as a crucial methodology for framing issues of class, race and gender. Yet, there is also a poetics that surpasses the documentary functions of your work. What is the role of poetics for you?

NY For my second solo exhibition, ‘Exile Is a Hard Job’ (1983), at L’ARC in the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, I collaborated with undocumented workers and their families in Faubourg Saint-Denis in Paris. I considered what would be the closest form of cultural communication with children and women. Anonymous singing – the bard culture kept alive in the music of figures such as Aşık Veysel and Pir Sultan Abdal – is very much a part of their own popular songs. There’s a strong oral tradition in Kurdish culture and many know the ancient poems by heart. I worked on an anthology of anonymous Kurdish women bards, compiled by Gérard Chaliand, a thinker known for his work on geographical and geopolitical philosophy. It was a way of starting a conversation with the work’s participants. Bard poetry has a different form and political stance from modern poetry. I used poems again in my interactive CD-ROM work Terra Nomade (1998).

ÖÖD How did you begin working with migrants and other individuals on the periphery of capitalism?

NY It required spending a lot of time with these economic migrants. You cannot all of a sudden appear at someone’s doorstep saying you want to interview them. They mostly lived in the banlieues. We would crowd together in the home of whoever had the largest house. In 1983, I worked with an assistant, a student of mine from the Sorbonne, where I was teaching at the Centre Saint Charles. By that point I had founded an association called Amicale France-Turquie. This organization cooperated with student groups to aid workers from Turkey who didn’t speak French in receiving medical treatment and immigration papers. It was through these student circles that I was directed to the Faubourg Saint-Denis. We went and they accepted me.

ÖÖD This connects back to your work on oral traditions and music.

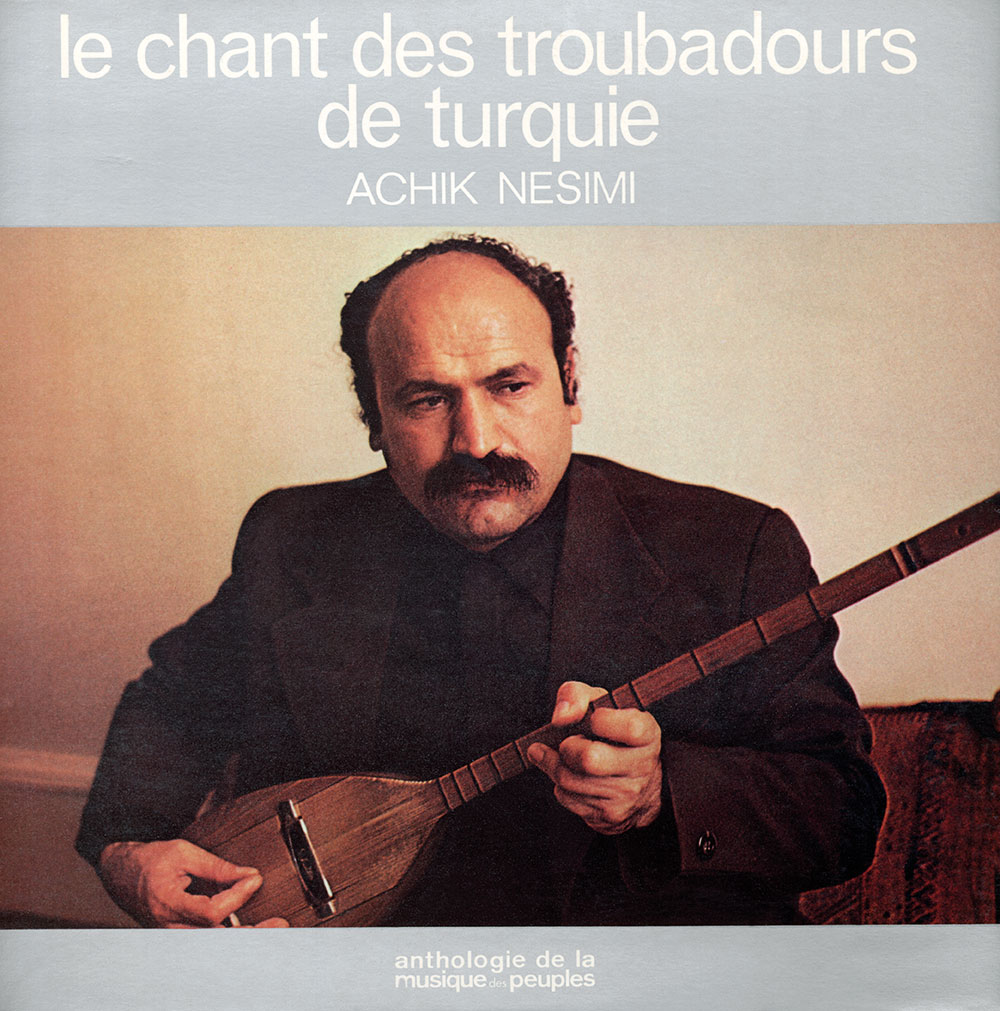

NY Yes, we went together afterwards to big textile workshops. There, I heard people who would play bard songs with a strong political awareness. I decided to use this folk culture, which merges all of the tonalities in Anatolia, in my work: I felt this was the right way to go, incorporating Anatolian kilim patterns with their poetry. In some of our workshops, they also used the string instrument we call the saz to make music with the poems, as seen in my videos.

The bard and folksinger Nesimi Çimen was a close friend. He had a record released here thanks to Dupaigne. I first got to know Çimen in Istanbul. Afterwards, when he came to Paris, we joined different meetings together with Kurds living here. He would always play his saz at these meetings. He also composed a musical poem for me. We organized concerts with Dupaigne so that Çimen could earn some money, and he stayed in my atelier when he had to escape Turkey. When Çimen accepted the proposal to make an LP with songs from the Turkish bardic tradition, we selected the poems together. I translated them into French for the liner notes – with my bad French! He also covered songs by a female bard from the 18th century. The LP, Le Chant des troubadours de Turquie (Song of the Turkish Troubadours, 1979) became very well-known and remained long in circulation.

ÖÖD You taught yourself how to make art, you educated yourself in the media you use in your work and you continue to stay informed about new developments. How has your new work evolved?

NY I made a piece titled Lapidation in 2010. On the internet, you can find various videos depicting public stoning. I found one where you could see men stoning a modern-dressed Kurdish woman in Baghdad. She was Shiite and dating a Sunni man. The men had stones in one hand and smartphones in the other; they were stoning her and shooting footage at the same time. They put these videos online to teach viewers a lesson. I watched and recorded those videos from my computer with my phone before they were taken down.

My recent work, Niqab Blues (2018), follows a similar logic. Women film each other putting on a niqab, and then upload the videos online to leave a trace. I shot these videos – some from Syria and Afghanistan – and left the refractions of this technology in the work. What I find interesting here is how people use technology and how the gesture of shooting these videos resonates with my own act of filming. They follow each other. I turn their temporary traces into permanent ones.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 203 with the headline ‘Nil Yalter’s Epic Poetry’

Nil Yalter is an artist based in Paris, France. She was born in 1938 in Cairo, Egypt, and was raised in Istanbul, Turkey. Her retrospective, ‘Exile Is a Hard Job’, is on view at Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany, until 2 June. On 22 June, the show will travel to the Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, USA, where it will be on view until 13 October.

Translated by Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu

Main Image: Rahime, Kurdish Woman from Turkey (detail), 1979, photographs, pencil, coloured pencil, paint and mixed media on cardboard, dimensions variable. Courtesy: the artist and Vehbi Koç Foundation Contemporary Art Collection, Istanbul; photograph: Hadiye Cangökçe