Picture Industry: A Provisional History of the Technical Image

A survey exhibition at LUMA Arles captures the history of mechanically-reproduced imagery from the 19th century to the present

A survey exhibition at LUMA Arles captures the history of mechanically-reproduced imagery from the 19th century to the present

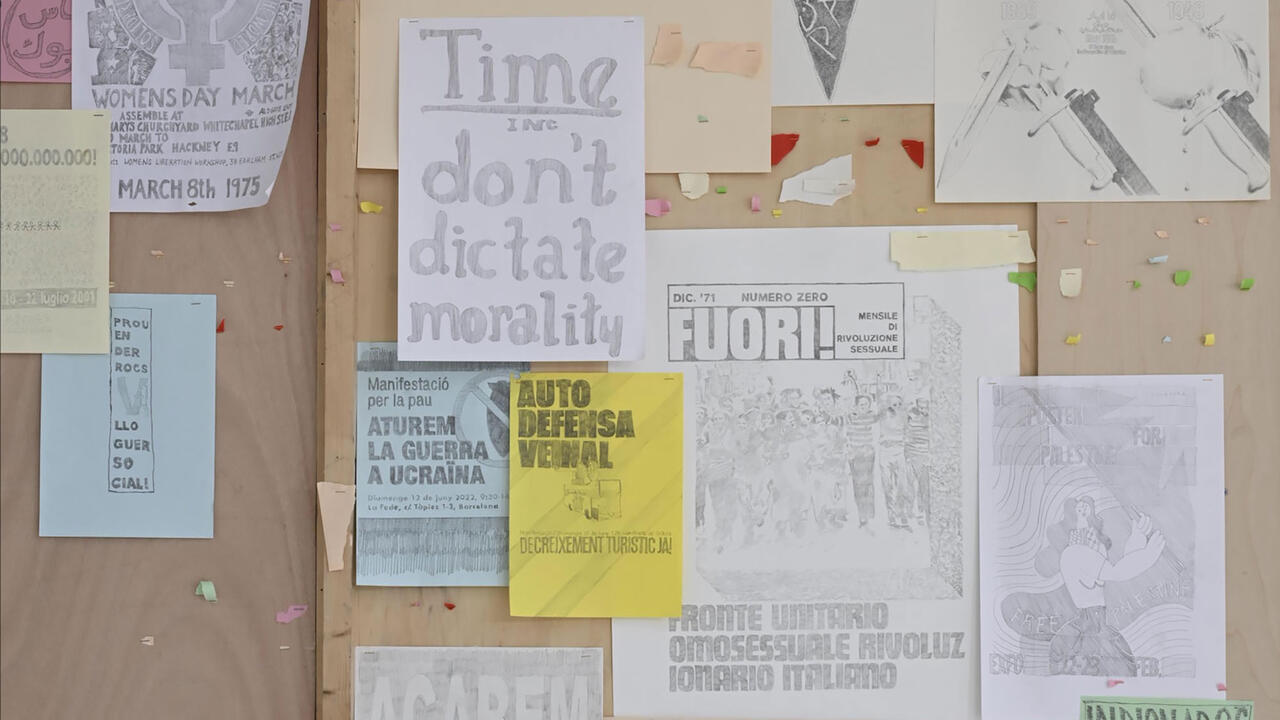

‘Picture Industry’ originated as part of Luma Arles’s 2016 exhibition ‘Systematically Open?’ and was presented in an expanded version last summer at Bard College, New York. This third iteration – subtitled ‘A Provisional History of the Technical Image, 1844–2018’ – encompassed more than 300 examples of printed matter, moving pictures and works of art, as well as a formidable 863-page anthology of texts. Artist Walead Beshty, who conceived the exhibition, borrowed philosopher Vilém Flusser’s term ‘technical image’ to address images forged by industrialization – collusions of humans with machines that are not so much reflections of the world as active, sly agents in its making.

Beshty indicted photography as a deficient term: archaic in an age of smart phones and arbitrary from its inception, as photographic processes overlapped with established technologies of printing and science. Accordingly, the first part of the exhibition drew on the camera work of physiologists (including Guillaume-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne’s notorious 1862 study of facial expressions triggered by electrocution), government-sponsored explorers (such as an 1870 report on mining prospects in the American Southwest), corporations (a 1904 United Fruit Company pamphlet promoting tourism in Jamaica), law enforcement (Alphonse Bertillon’s 1896 treatise on criminal identification) as well as social welfare reformers (Lewis Hine’s investigations into working conditions in the US, which he began in 1907). Two technofossils embody the violence that runs throughout: a rifle-camera invented by Étienne-Jules Marey in 1882 to study animal locomotion and a startling device used during World War II to train Japanese machine gunners by shooting pictures rather than bullets. Indeed, ‘Picture Industry’ unwaveringly implicates photographic practices historically in domination: whether colonialism and racism or class division and criminalization.

Beautiful: Bringing the War Home'. Courtesy: the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

‘Too many exhibitions unwittingly reproduce a hierarchy of objects based on their availability to connoisseurship,’ writes Beshty in the show’s catalogue–anthology, chastising art historians for their protective categories and neat lineages. Texts accompanying items on display refused to afford a unifying authority, comprising instead lengthy and varied citations from scholarly essays, interviews and websites. Presented in the manner of a roughly chronological ledger, the exhibition was ostensibly not structured thematically. However, the cluster of display cases that introduced the second floor could easily have been headed ‘Racial Segregation and the Civil Rights Movement in the US’. These included extraordinary photojournalism by Gordon Parks from issues of Life magazine, spanning 1947 to 1968. Beshty was wise not to have curated his own art into the exhibition, although many items are credited to his collection. Yet, a pristine wall-mounted vitrine containing the book Twelve Million Black Voices (1947), with pages depicting a lynching, juxtaposed above a 1963 Life spread in which Charles Moore documented police brutality in Alabama – the source of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen Race Riot (1964) – is a montage so audaciously sculptural that it somehow exceeds unambiguous exhibition display.

Flusser imagined the apparatuses producing ‘technical images’ as functioning automatically, without humans. With a convincing case made for the independent agency of photographic images through evidence derived from diverse professions and fields, it is curious to witness the sleight-of-hand with which the presentation thus segued into a more conventional exhibition of contemporary-art-proper and authored appropriation. (Where it might, instead, have explored military drone imaging or artificial intelligence visualizations, for example.) Following a transition from the pages of business magazine Fortune (where Walker Evans was staff photographer from 1945 to 1965) to the art context of Artforum (with Lynda Benglis’s infamous self-portrait-with-dildo that appeared among the gallery ads in 1974), the exhibition was thereon dominated by artists. Arresting images from newspaper front pages following the 9/11 attacks, for instance, were presented in the form of Hans-Peter Feldmann’s 9/12 Front Page (2001) rather than on their own terms as the viral visual testimony of countless devices and people.

A US-dominated curriculum presided over the exhibition’s central section, with now-classic works by Martha Rosler (House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72), Sherrie Levine (After Walker Evans, 1981) as well as contributions from Gretchen Bender, Barbara Bloom, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, Glenn Ligon, Robert Mapplethorpe and Allan McCollum, among others. Kelley Walker had a prominent presence with two examples of his discomforting ‘Schema’ series from 2003: wallpaper printed from scans of toothpaste-smeared images, one featuring an air crash, another a white cop beating a black youth.

Several works of art compellingly linked back to the disciplinary vein of early photographic techniques in relation to the currency of labour. Harun Farocki’s Workers Leaving the Factory in 11 Decades (2006) comprises 12 monitors with found footage echoing the subject of the first film screened by Louis and Auguste Lumière in 1895, while Cameron Rowland’s Handpunch (2014–15) showed snapshots of sinister-looking biometric devices used to measure employee working hours.

‘Picture Industry’ is an accomplished exhibition, yet it is often at its strongest when images are unburdened from being ‘properly’ art and eight ghostly items, made anonymously in the 1960s, almost stole the show. Faced with government-approved music and without record vinyl, a Soviet bootlegger devised an ingenious techno-cultural hack: forbidden jazz and rock could be inscribed into the ghostly bone images of discarded X-ray acetates.

'Picture Industry' runs at Luma Arles, France, until 6 January 2019.

Main image: Liz Glynn, Anonymous Needs and Desires (Various Castoffs: Ceramic Tile, Potato Chips, Garlic, Men’s Socks,Blackberry, iPod, Baby Food, Perfume, Chocolate, and Cigarettes), 2012, plomp durci. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Robert Acklen-Brecˇko, Walead, Beshty Studios, Inc.